You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Touch screens in cars was a bad idea. They’ve gone TOO far; UPDATE: EuroNCAP to now incentivize buttons!

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?IIVI

Superstar

I think a decent trade-off/compromise:

What you use when driving = make physical.

What you use when parked = make touchscreen.

Make majority touchscreen capable so the driver can opt in/out.

What you use when driving = make physical.

What you use when parked = make touchscreen.

Make majority touchscreen capable so the driver can opt in/out.

null

...

I miss this shyt. All I need is Bluetooth for my music and I'm gucci

and e46 with a pop up screen >>>> most cars today

OR the recent porsche cayman dash also hit the right balance.

-

EQS abomination

Rejoice! Carmakers Are Embracing Physical Buttons Again

Amazingly, reaction times using screens while driving are worse than being drunk or high—no wonder 90 percent of drivers hate using touchscreens in cars. Finally the auto industry is coming to its senses.

Last edited:

Spin the block in a few years. I’m usually more correct than not. Thats why so many of you find my stance on issues that cost democrats in 2024 to be so grating. You dont see around the corner...You honestly a decent thread maker when not focusing exclusively on party politics.

You should make more regular threads

Correct or not, its still annoying rehashing the same topic over and over and over. Nobody wants to discuss trannies every other day. I've never even met one in real life. With less and less posters on this site every year, its hard to fine interesting threads to comment on sometimes.Spin the block in a few years. I’m usually more correct than not. Thats why so many of you find my stance on issues that cost democrats in 2024 to be so grating. You dont see around the corner...

Rejoice! Carmakers Are Embracing Physical Buttons Again

Amazingly, reaction times using screens while driving are worse than being drunk or high—no wonder 90 percent of drivers hate using touchscreens in cars. Finally the auto industry is coming to its senses.www.wired.com

Part 1:

AUTOMAKERS THAT NEST key controls deep in touchscreen menus—forcing motorists to drive eyes-down rather than concentrate on the road ahead—may have their non-US safety ratings clipped next year.

From January, Europe’s crash-testing organization EuroNCAP, or New Car Assessment Program, will incentivize automakers to fit physical, easy-to-use, and tactile controls to achieve the highest safety ratings. “Manufacturers are on notice,” EuroNCAP’s director of strategic development Matthew Avery tells WIRED, “they’ve got to bring back buttons.”

Motorists, urges EuroNCAP’s new guidance, should not have to swipe, jab, or toggle while in motion. Instead, basic controls—such as wipers, indicators, and hazard lights—ought to be activated through analog means rather than digital.

Driving is one of the most cerebrally challenging things humans manage regularly—yet in recent years manufacturers seem almost addicted to switch-free, touchscreen-laden cockpits that, while pleasing to those keen on minimalistic design, are devoid of physical feedback and thus demand visual interaction, sometimes at the precise moment when eyes should be fixed on the road.

A smattering of automakers are slowly admitting that some smart screens are dumb. Last month, Volkswagen design chief Andreas Mindt said that next-gen models from the German automaker would get physical buttons for volume, seat heating, fan controls, and hazard lights. This shift will apply “in every car that we make from now on,” Mindt told British car magazine Autocar.

Acknowledging the touchscreen snafus by his predecessors—in 2019, VW described the “digitalized” Golf Mk8 as “intuitive to operate” and “progressive” when it was neither—Mindt said, “we will never, ever make this mistake anymore … It’s not a phone, it’s a car.”

Still, “the lack of physical switchgear is a shame” is now a common refrain in automotive reviews, including on WIRED. However, a limited but growing number of other automakers are dialing back the digital to greater or lesser degrees. The latest version of Mazda’s CX-60 crossover SUV features a 12.3-inch infotainment screen, but there’s still physical switchgear for operating the heater, air-con, and heated/cooled seats. While it’s still touch-sensitive, Mazda’s screen limits what you can prod depending on the app you’re using and whether you’re in motion. There’s also a real click wheel.

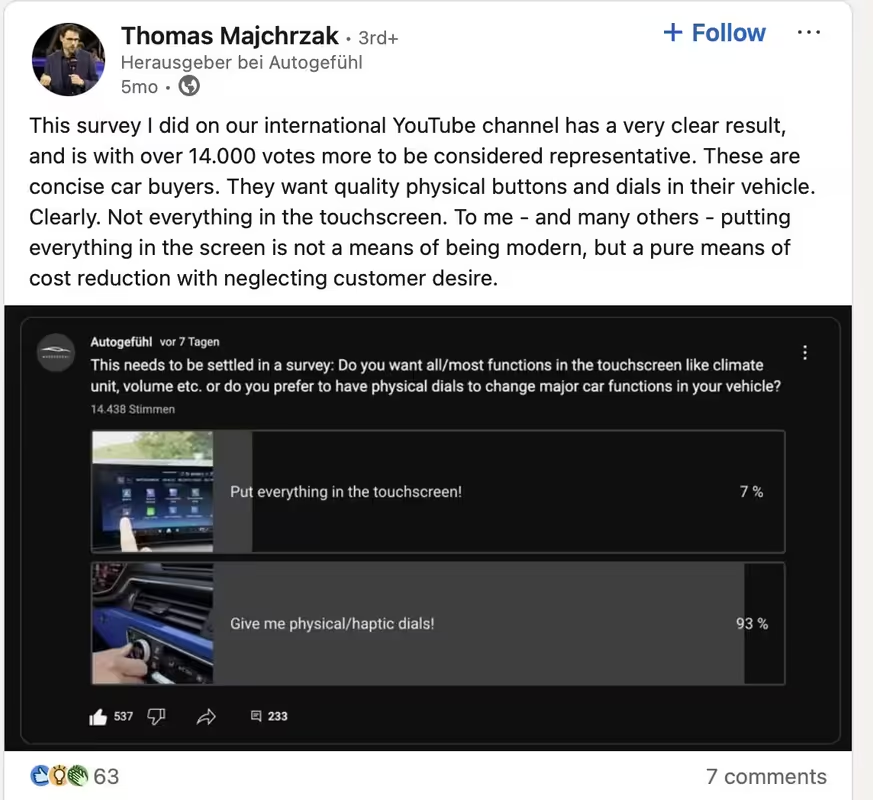

But many other automakers keep their touchscreen/slider/haptic/LLM doohickeys. Ninety-seven percent of new cars released after 2023 contain at least one screen, reckons S&P Global Mobility. Yet research last year by Britain’s What Car? magazine found that the vast majority of motorists prefer dials and switches to touchscreens. A survey of 1,428 drivers found that 89 percent preferred physical buttons.

Motorists, it seems, would much prefer to place their driving gloves in a glove compartment that opens with a satisfying IRL prod on a gloriously yielding and clicking clasp, rather than diving into a digital submenu. Indeed, there are several YouTube tutorials on how to open a Tesla’s glove box. “First thing,” starts one, “is you’re going to click on that car icon to access the menu settings, and from there on, you’re going to go to controls, and right here is the option to open your glove box.” As Ronald Reagan wrote, “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.”

Voice Control Reversion

The mass psychosis to fit digital cockpits is partly explained by economics—updatable touchscreens are cheaper to fit than buttons and their switchgear—but “there’s also a natural tendency [among designers] to make things more complex than they need to be,” argues Steven Kyffin, a former dean of design and pro vice-chancellor at Northumbria University in the UK (the alma mater of button-obsessed Sir Jonny Ive).

“Creating and then controlling complexity is a sign of human power,” Kyffin says. “Some people are absolutely desperate to have the flashiest, most minimalist, most post-modern-looking car, even if it is unsafe to drive because of all the distractions.”

Automakers shouldn’t encourage such consumers. “It is really important that steering, acceleration, braking, gear shifting, lights, wipers, all that stuff which enables you to actually drive the car, should be tactile,” says Kyffin, who once worked on smart controls for Dutch electronics company Philips. “From an interaction design perspective, the shift to touchscreens strips away the natural affordances that made driving intuitive,” he says.

“Traditional buttons, dials, and levers had perceptible and actionable qualities—you could feel for them, adjust them without looking, and rely on muscle memory. A touchscreen obliterates this," says Kyffin. "Now, you must look, think, and aim to adjust the temperature or volume. That’s a huge cognitive load, and completely at odds with how we evolved to interact with driving machines while keeping our attention on the road.”

To protect themselves from driver distraction accusations, most automakers are experimenting with artificial intelligence and large language models to improve voice-activation technologies, encouraging drivers to interact with their vehicles via natural speech, negating the need to scroll through menus. Mercedes-Benz, for example, has integrated ChatGPT into its vehicles' voice-control, but it's far too early to say whether such moves will finally make good on the now old and frequently broken promise of voice-controlled car systems from multiple manufacturers.

In fact, sticking with Mercedes, the tyranny of touchscreens looks set to be with us for some time yet. The largest glass dashboard outside of China is the 56-inch, door-to-door “Hyperscreen” in the latest S-Class Mercedes comprising, in one curvaceous black slab, a 12.3-inch driver’s display, a 12.3-inch passenger touchscreen, and a 17.7-inch central touchscreen that, within submenus, houses climate control and other key functions.

To turn on the heated steering wheel on a Nissan Leaf, there’s an easy-to-reach-without-looking square button on the dashboard. To be similarly toasty on the latest Mercedes, you will have to pick through a menu on the MBUX Hyperscreen by navigating to “Comfort Settings.” (You can also use voice control, by saying “Hey Mercedes,” but even if this worked 100 percent of the time, it is not always ideal to speak aloud to your auto, as passengers may well attest.)

Tesla might have popularized the big-screen digital cockpit, but Buick started the trend with its Riviera of 1986, the first car to be fitted with an in-dash touchscreen, a 9-inch, 91-function green-on-black capacitive display known as the Graphic Control Center that featured such delights as a trip computer, climate control, vehicle diagnostics, and a maintenance reminder feature. By General Motors' own admission, drivers hated it, and it was this seemingly trailblazing feature, along with a reduction in the car's size, that supposedly led to the model's year-on-year sales plummeting by 63 percent.

Buick soon ditched the Riviera’s screen, but not before a TV science program reviewing the car asked the obvious question: “Is there a built-in danger of looking away from the road while you’re trying to use it?”

Reaction Times Worse Than Drunk or High

Screens or not, “motorists shouldn’t forget they are driving [potentially] deadly weapons,” says Kyffin. An average of 112 Americans were killed every day on US roads in 2023, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s most recent full-year statistics. That’s equivalent to a plane crash every day.

Despite the proliferation of advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), motor crash fatalities in the United States have increased 21 percent in the past 15 years. Forty thousand people have died on the roads in each of the past three years for which complete federal records are available.

In-vehicle infotainment systems impair reaction times behind the wheel more than alcohol and narcotics use, according to researchers at independent British consultancy TRL. The five-year-old study, commissioned by road-safety charity IAM RoadSmart, discovered that the biggest negative impact on drivers’ reactions to hazards came when using Apple CarPlay by touch. Reaction times were nearly five times worse than when a driver was at the drink-drive limit, and nearly three times worse than when high on cannabis.

Part 2:

A study carried out by Swedish car magazine Vi Bilägare in 2022 showed that physical buttons are much less time-consuming to use than touchscreens. Using a mix of old and new cars, the magazine found that the most straightforward vehicle to change controls on was the 2005 Volvo V70 festooned with buttons and no screens. A range of activities such as increasing cabin temperature, tuning the radio, and turning down instrument lighting could be handled within 10 seconds in the old Volvo, and with only a minimum of eyes-down. However, the same tasks on an electric MG Marvel R compact SUV took 45 seconds, requiring precious travel time to look through the nested menus. (The tests were done on an abandoned airfield.)

Distraction plays a role in up to 25 percent of crashes in Europe, according to a report from the European Commission published last year. “Distraction or inattention while driving leads drivers to have difficulty in lateral control of the vehicle, have longer reaction times, and miss information from the traffic environment,” warned the report.

A Touch Too Far

Seemingly learning little from Buick’s Riviera, BMW reintroduced touchscreens in 2001. The brand’s iDrive system combined an LCD touchscreen with a rotary control knob for scrolling through menus. Other carmakers also soon introduced screens, although with limitations. Jaguar and Land Rover would only show certain screen functions to drivers, with passengers tasked with the fiddly bits. Toyota and Lexus cars had screens that worked only when the handbrake was applied.

With curved pillar-to-pillar displays, holographic transparent displays, displays instead of rear-view mirrors, and head-up displays (HUD), it’s clear many in-car devices are fighting for driver attention. HUDs might not be touch-sensitive, but projecting a plethora of vehicle data, as well as maps, driver aids, and multimedia information, onto the windscreen could prove as distracting as toggling through menus.

“Almost every vehicle-maker has moved key controls onto central touchscreens, obliging drivers to take their eyes off the road and raising the risk of distraction crashes,” EuroNCAP’s Avery tells WIRED. “Manufacturers are realizing that they’ve probably gone too far with [fitting touchscreens].”

“A new part of our 2026 ratings is going to relate to vehicle controls,” says Avery. “We want manufacturers to preserve the operation of five principal controls to physical buttons, so that’s wipers, lights, indicators, horn, and hazard warning lights.” This however does not address the frequent needs for drivers to adjust temperature, volume, or change driver warning systems settings (an endeavor all too commonly requiring navigating down through multiple submenus).

Perhaps unfortunately, it looks like continuing with touchscreens won’t lose manufacturers any of the coveted stars in EuroNCAP’s five-star safety ratings. “It’s not the case that [automakers] can’t get five stars unless they’ve got buttons, but we’re going to make entry to the five-star club harder over time. We will wind up the pressure, with even stricter tests in the next three-year cycle starting in 2029.”

Regardless, Avery believes auto manufacturers around the world will bring back buttons. “I will be very surprised if there are markets where manufacturers have a different strategy,” he says.

“From a safety standpoint, reducing the complexity of performing in-vehicle tasks is a good thing,” says Joe Young, the media director for the insurance industry-backed Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS). “The research is clear that time spent with your eyes off the road increases your risk of crashing, so reducing or eliminating that time by making it easier to find and manipulate buttons, dials, and knobs is an improvement.”

Neither Young nor Jake Nelson, director of traffic safety research for AAA, would be drawn on whether US automakers—via the US version of NCAP—would adopt EuroNCAP’s button nudges. “Industry design changes in the US market are more likely to occur based on strong consumer demand,” Nelson says. “It would be ideal to see better coordination between NCAP and EuroNCAP, however, we have not observed much influence in either direction.”

Nevertheless, Nelson agrees that “basic functions, such as climate control, audio, and others, should be accessible via buttons.” He adds that the “design of vehicle technologies should be as intuitive as possible for users” but that the “need for tutorials suggests otherwise.”

For Edmund King, president of the AA (the UK equivalent to AAA), driver distraction is personal. “When cycling, I often see drivers concentrating on their touchscreens rather than the road ahead," he says. "Technology should be there to help drivers and passengers stay safe on the roads, and that should not be to the detriment of other road users.”

Screen Out

The deeper introduction of AI into cars as part of software-defined vehicles could result in fewer touchscreens in the future, believes Dale Harrow, chair and director of the Intelligent Mobility Design Center at London’s Royal College of Art.

Eye scanners in cars are already watching how we’re driving and will prod us—with haptic seat buzzing and other alerts—when inattention is detected. In effect, today’s cars nag drivers not to use the touchscreens provided. “[Automakers] have added [touchscreen] technologies without thinking about how drivers use vehicles in motion,” says Harrow. “Touchscreens have been successful in static environments, but [that] doesn’t transfer into dynamic environments. There’s sitting in a mock-up of a car and thinking it’s easy to navigate through 15 layers, but it’s far different when the car is in motion.”

Crucially, touchscreens are ubiquitous partly because of cost—it’s cheaper to write lines of computer code than to add wires behind buttons on a physical dash. And there are further economies of scale for multi-brand car companies such as Volkswagen Group, which can put the same hardware and software in a Skoda as they do a Seat, changing just the logo pop-ups.

Additionally, over-the-air updates almost require in-car computer screens. A car’s infotainment system, the operation of ambient lighting, and other design factors are an increasingly important part of car design, and they need a screen for manufacturers to incrementally improve software-defined vehicles after rolling off production lines. Adding functionality isn’t nearly as simple when everything is buttons.

Not all screens cause distractions, of course—reversing cameras are now essential equipment, and larger navigation screens mean less time looking down for directions—but to demonstrate how touchscreens and voice control aren’t as clever as many think they are, consider the cockpit of an advanced passenger jet.

The Boeing 777X has touchscreens, but they are used by pilots only for data input—never for manipulation of controls. Similarly, the cockpit of an Airbus A350 also has screens, but they’re not touch-sensitive, and there are no voice-activated controls either. Instead, like in the 777X, there are hundreds of knobs, switches, gauges, and controls.

Of course, considering the precious human cargo and the fact that an A350 starts at $308 million, you can't fault Airbus for wanting pilots' eyes on the skies rather than screens. There are slightly fewer tactile controls in the $429,000 Rolls-Royce Spectre, the luxury car company’s first electric vehicle. There’s a screen for navigation, yes, but also lots of physical switchgear. Reviewing the new Black Badge edition of the high-end EV, Autocar said the vehicle’s digital technology was “integrated with restraint.”

Along with Volkswagen reintroducing physical buttons for functions like volume and climate control, Subaru is also bringing back physical knobs and buttons in the 2026 Outback. Hyundai has added more buttons back into the new Santa Fe, with design director Ha Hak-soo confessing to Korean JoongAng Daily towards the end of last year that the company found customers didn't like touchscreen–focused systems. And, if EuroNCAP gets its way, that’s likely the direction of travel for all cars. Buttons are back, baby.

A study carried out by Swedish car magazine Vi Bilägare in 2022 showed that physical buttons are much less time-consuming to use than touchscreens. Using a mix of old and new cars, the magazine found that the most straightforward vehicle to change controls on was the 2005 Volvo V70 festooned with buttons and no screens. A range of activities such as increasing cabin temperature, tuning the radio, and turning down instrument lighting could be handled within 10 seconds in the old Volvo, and with only a minimum of eyes-down. However, the same tasks on an electric MG Marvel R compact SUV took 45 seconds, requiring precious travel time to look through the nested menus. (The tests were done on an abandoned airfield.)

Distraction plays a role in up to 25 percent of crashes in Europe, according to a report from the European Commission published last year. “Distraction or inattention while driving leads drivers to have difficulty in lateral control of the vehicle, have longer reaction times, and miss information from the traffic environment,” warned the report.

A Touch Too Far

Seemingly learning little from Buick’s Riviera, BMW reintroduced touchscreens in 2001. The brand’s iDrive system combined an LCD touchscreen with a rotary control knob for scrolling through menus. Other carmakers also soon introduced screens, although with limitations. Jaguar and Land Rover would only show certain screen functions to drivers, with passengers tasked with the fiddly bits. Toyota and Lexus cars had screens that worked only when the handbrake was applied.

With curved pillar-to-pillar displays, holographic transparent displays, displays instead of rear-view mirrors, and head-up displays (HUD), it’s clear many in-car devices are fighting for driver attention. HUDs might not be touch-sensitive, but projecting a plethora of vehicle data, as well as maps, driver aids, and multimedia information, onto the windscreen could prove as distracting as toggling through menus.

“Almost every vehicle-maker has moved key controls onto central touchscreens, obliging drivers to take their eyes off the road and raising the risk of distraction crashes,” EuroNCAP’s Avery tells WIRED. “Manufacturers are realizing that they’ve probably gone too far with [fitting touchscreens].”

“A new part of our 2026 ratings is going to relate to vehicle controls,” says Avery. “We want manufacturers to preserve the operation of five principal controls to physical buttons, so that’s wipers, lights, indicators, horn, and hazard warning lights.” This however does not address the frequent needs for drivers to adjust temperature, volume, or change driver warning systems settings (an endeavor all too commonly requiring navigating down through multiple submenus).

Perhaps unfortunately, it looks like continuing with touchscreens won’t lose manufacturers any of the coveted stars in EuroNCAP’s five-star safety ratings. “It’s not the case that [automakers] can’t get five stars unless they’ve got buttons, but we’re going to make entry to the five-star club harder over time. We will wind up the pressure, with even stricter tests in the next three-year cycle starting in 2029.”

Regardless, Avery believes auto manufacturers around the world will bring back buttons. “I will be very surprised if there are markets where manufacturers have a different strategy,” he says.

“From a safety standpoint, reducing the complexity of performing in-vehicle tasks is a good thing,” says Joe Young, the media director for the insurance industry-backed Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS). “The research is clear that time spent with your eyes off the road increases your risk of crashing, so reducing or eliminating that time by making it easier to find and manipulate buttons, dials, and knobs is an improvement.”

Neither Young nor Jake Nelson, director of traffic safety research for AAA, would be drawn on whether US automakers—via the US version of NCAP—would adopt EuroNCAP’s button nudges. “Industry design changes in the US market are more likely to occur based on strong consumer demand,” Nelson says. “It would be ideal to see better coordination between NCAP and EuroNCAP, however, we have not observed much influence in either direction.”

Nevertheless, Nelson agrees that “basic functions, such as climate control, audio, and others, should be accessible via buttons.” He adds that the “design of vehicle technologies should be as intuitive as possible for users” but that the “need for tutorials suggests otherwise.”

For Edmund King, president of the AA (the UK equivalent to AAA), driver distraction is personal. “When cycling, I often see drivers concentrating on their touchscreens rather than the road ahead," he says. "Technology should be there to help drivers and passengers stay safe on the roads, and that should not be to the detriment of other road users.”

Screen Out

The deeper introduction of AI into cars as part of software-defined vehicles could result in fewer touchscreens in the future, believes Dale Harrow, chair and director of the Intelligent Mobility Design Center at London’s Royal College of Art.

Eye scanners in cars are already watching how we’re driving and will prod us—with haptic seat buzzing and other alerts—when inattention is detected. In effect, today’s cars nag drivers not to use the touchscreens provided. “[Automakers] have added [touchscreen] technologies without thinking about how drivers use vehicles in motion,” says Harrow. “Touchscreens have been successful in static environments, but [that] doesn’t transfer into dynamic environments. There’s sitting in a mock-up of a car and thinking it’s easy to navigate through 15 layers, but it’s far different when the car is in motion.”

Crucially, touchscreens are ubiquitous partly because of cost—it’s cheaper to write lines of computer code than to add wires behind buttons on a physical dash. And there are further economies of scale for multi-brand car companies such as Volkswagen Group, which can put the same hardware and software in a Skoda as they do a Seat, changing just the logo pop-ups.

Additionally, over-the-air updates almost require in-car computer screens. A car’s infotainment system, the operation of ambient lighting, and other design factors are an increasingly important part of car design, and they need a screen for manufacturers to incrementally improve software-defined vehicles after rolling off production lines. Adding functionality isn’t nearly as simple when everything is buttons.

Not all screens cause distractions, of course—reversing cameras are now essential equipment, and larger navigation screens mean less time looking down for directions—but to demonstrate how touchscreens and voice control aren’t as clever as many think they are, consider the cockpit of an advanced passenger jet.

The Boeing 777X has touchscreens, but they are used by pilots only for data input—never for manipulation of controls. Similarly, the cockpit of an Airbus A350 also has screens, but they’re not touch-sensitive, and there are no voice-activated controls either. Instead, like in the 777X, there are hundreds of knobs, switches, gauges, and controls.

Of course, considering the precious human cargo and the fact that an A350 starts at $308 million, you can't fault Airbus for wanting pilots' eyes on the skies rather than screens. There are slightly fewer tactile controls in the $429,000 Rolls-Royce Spectre, the luxury car company’s first electric vehicle. There’s a screen for navigation, yes, but also lots of physical switchgear. Reviewing the new Black Badge edition of the high-end EV, Autocar said the vehicle’s digital technology was “integrated with restraint.”

Along with Volkswagen reintroducing physical buttons for functions like volume and climate control, Subaru is also bringing back physical knobs and buttons in the 2026 Outback. Hyundai has added more buttons back into the new Santa Fe, with design director Ha Hak-soo confessing to Korean JoongAng Daily towards the end of last year that the company found customers didn't like touchscreen–focused systems. And, if EuroNCAP gets its way, that’s likely the direction of travel for all cars. Buttons are back, baby.

I dont personally care about thread topics you like nor do I care about your affiliation to an issue. I post data and surveys and polls.Correct or not, its still annoying rehashing the same topic over and over and over. Nobody wants to discuss trannies every other day. I've never even met one in real life. With less and less posters on this site every year, its hard to fine interesting threads to comment on sometimes.

I’m objective about the issue. Its business.

Givethanks

Superstar

They need to start fixing the center consoles of cars too

Why they trying to separate the two front passengers for? Who asked for that.

Why they trying to separate the two front passengers for? Who asked for that.

beenz

Rap Guerilla

actual tactile buttons cost more money, which is why the car manufacturers went all in on touch screens. furthermore, the computers allow these cars to collect even more information about u and lock features behind a paywall..

a mix of both is good.