Y'all young cats are chosing terrible choices

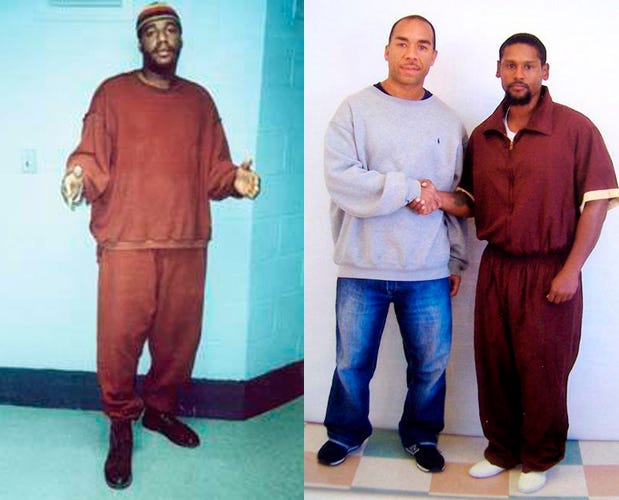

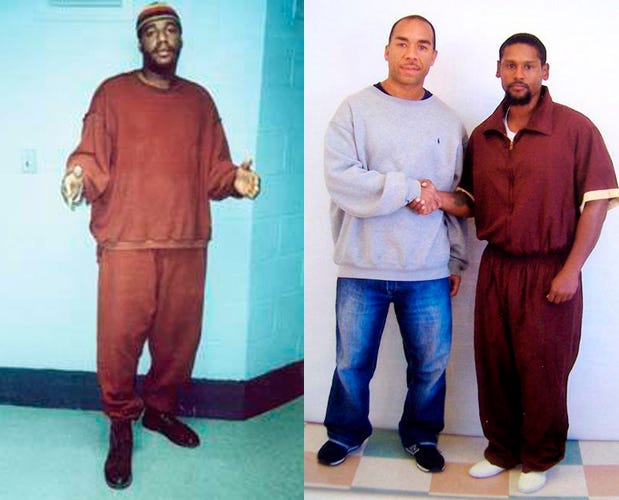

in REAL life it's these dudes

went from the glamorous life to

How Cool C and Steady B Robbed a Bank, Killed a Cop and Lost Their Souls

Philly rap legends Schoolly D, DJ Cash Money and others try to make sense of a tragic journey

By Michael A. Gonzales

“Philadelphia banks are not hit by takeover teams very often, and with good reason: there are few ways out.” ~Duane Swierczynski, The Wheelman

It was nearly opening time at the PNC Bank on Rising Sun Avenue in the Olney section of North Philadelphia. As early pedestrians ambled past on the cold, foggy morning of Tuesday, January 2, 1996, the bank manager entered the low-rise building alone. At the SEPTA bus stop a few feet away, a pair of construction workers casually looked on. Wearing white hardhats, the two young men appeared to be simply sipping hot coffee, puffing on Newports and talking about the forthcoming blizzard. Except they weren’t.

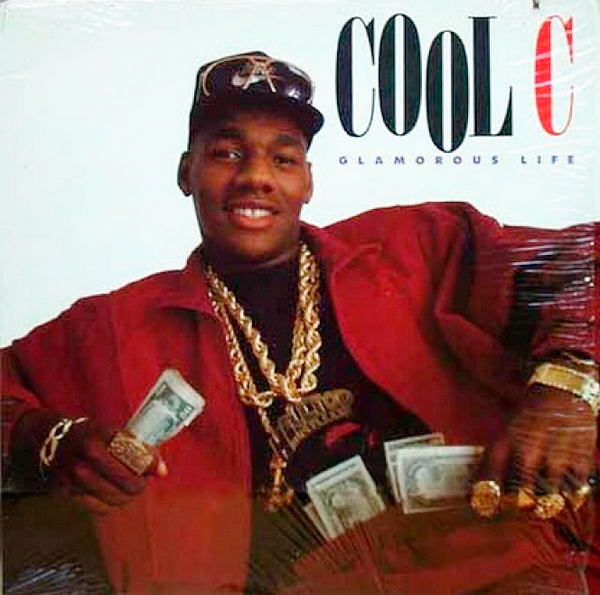

Instead those two men — later identified as Christopher Roney, 26, and Mark Canty, 22 — were watching every move, waiting for the opportunity to bum rush the manager and rob the bank. On the streets of Philly, Roney was more popularly known by his professional hip-hop handle, Cool C. A hit song called “Glamorous Life” had made him a local celebrity back in 1989, but a lot had changed since then.

Canty was not famous, having been recently fired from a lunch-room gig at Albert Einstein Medical Center. But rounding out the motley trio was another familiar face: Warren McGlone, 26, who acted as the heist’s wheelman. McGlone was well known as a key figure in the Philly hip-hop scene, a chubby microphone sensation who called himself Steady B.

DJ Ease, Cool C and Steady B as the short-lived C.E.B. (Countin’ Endless Bank), one year before the attempted bank robbery

Canty carried a 9 millimeter and Roney a 380-caliber semi-automatic; both knew this branch had no security guard. When PNC’s first employee arrived, they pushed their way through the building’s doorway. The manager was forced to the floor while Canty took an employee to the back to access the vault. Having pulled off successful heists previously with the rappers, Canty surely anticipated a major payday. So what if it was supposed to snow? Later that day, it’d be raining green.

However, within moments of entering the PNC Bank, the silent alarm was tripped; the pair’s clumsily thought-out plan began to go haywire.

Riding solo in patrol car #2516, female Philadelphia police officer Lauretha Vaird, a former teacher’saide who had joined the force nearly nine years prior, responded to the call. As Vaird stepped towards the bank door with her gun drawn, Canty reportedly screamed to Roney, “Here comes the heat!”

The Sound of Philadelphia

Back in the late 1980s, when hip-hop was still maturing into a commercial art form, Cool C and Steady B were ghetto superstars. They performed shows at Fairmount Park’s fabled plateau in West Philadelphia and had their 12-inches and albums stuffed into metal racks at Funk-O-Mart on Market Street. Having met when they were students at Overbrook High School, which Will Smith also attended, both were signed to local label Pop Art Records who, in turn, got them distribution and marketing deals with larger labels.

Although Steady B and Cool C were young boys, still teens when they signed on the dotted line, they were repping the region well, working as hard as their elders Lady B, Schoolly D and MC Breeze. “Those guys were the quintessential Philly rappers,” MK Asante, author of the Philly coming-of age-memoir Buck, says. “They had that Philly aggression and cockiness that just made them completely ours. Steady B came out with a song dissing LL Cool J [“I’ll Take Your Radio”], and Cool C made a track talking about the Juice Crew [“Juice Crew Dis”]. ”

Pop Art was owned by Lawrence Goodman and overseen by his brother, Dana. The label had previously released techno-funk singles by Galaxxy, disco-soul from Major Harris and early singles by Juice Crew comrades Roxanne Shanté and Biz Markie. In the 1970s, years before fictional gangster rapper-turned-music-mogul Lucious Lyon made Philadelphia rap fodder for culture vultures on Empire, Goodman had conceived the label with Ron Aikens while they served time at Graterford prison.

Located in West Philly on City Line Avenue, the small label soon became a hip-hop beacon in the brotherly love metropolis. Pop Art’s first forays into rap were Eddie D’s “Cold Cash Money” and Roxanne Shanté’s “Roxanne Revenge” in 1984. These led to a run of impactful releases from the label, which played an important role in the emerging rap marketplace. What Philadelphia International meant to soul in the 70s, Pop Art was to rap in the 80s.

“Hip-hop was still very much a singles medium back then, and Pop Art Records was more influential than they’re given credit for,” Rolling Stone writer and pop music historian Jesse Serwer explains. In 2008, he wrote about the rise and fall of the pioneering label in the “Philly Issue” of Wax Poetics. “When Marley Marl and those guys couldn’t get deals in New York City, they came to Philadelphia and signed with Pop Art. The Goodmans were street dudes, but they knew hip-hop.”

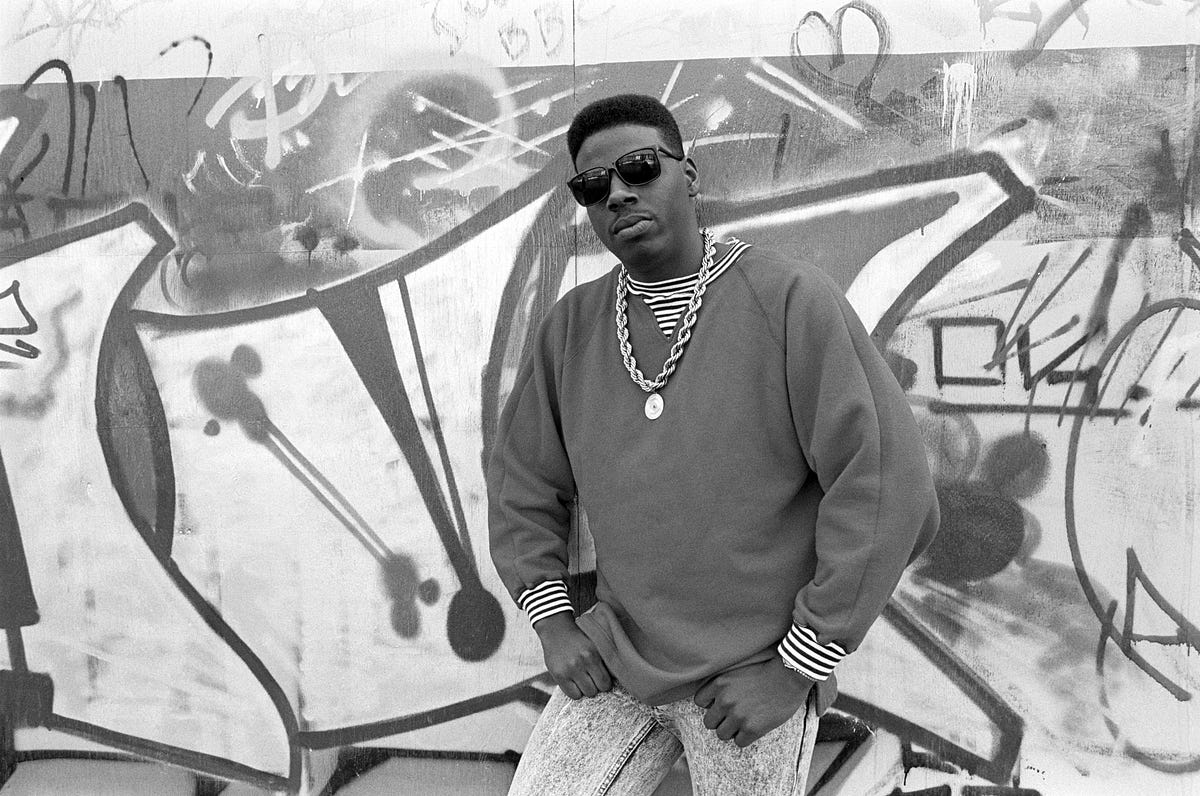

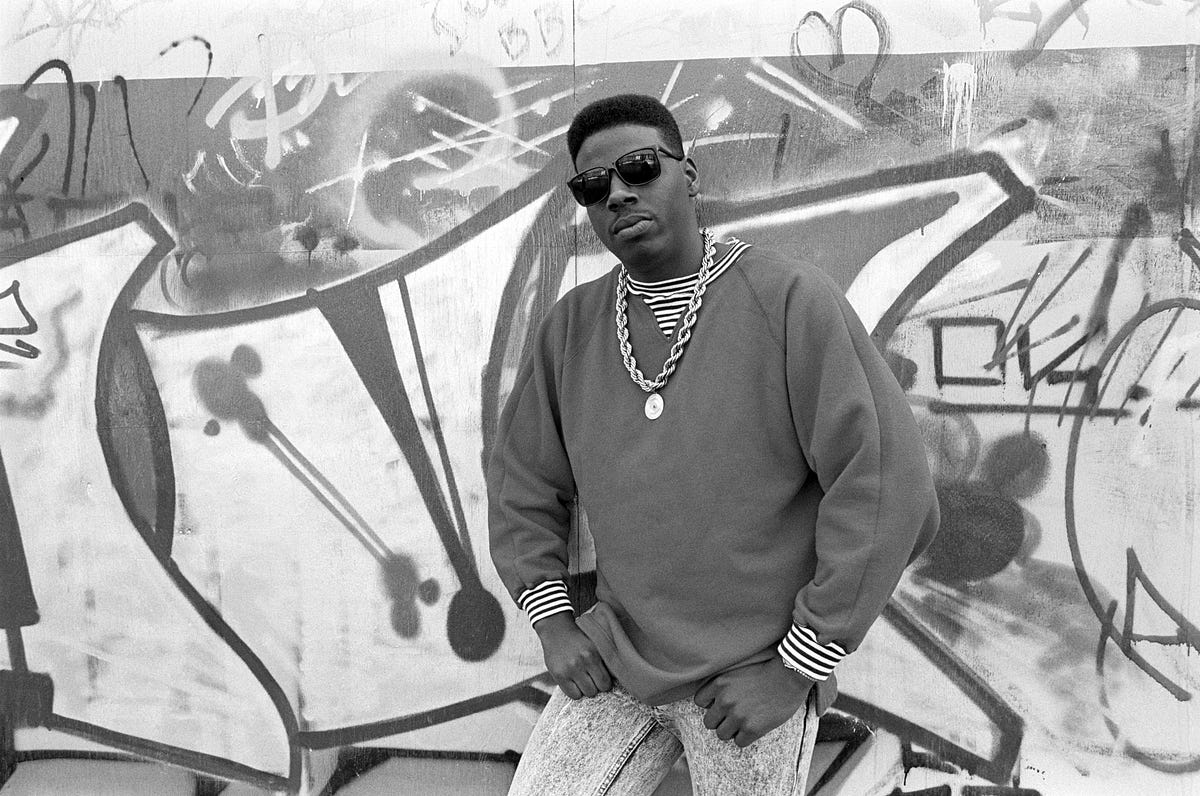

Steady B promotional photo

In 1986, after producer Marley Marl jumped ship and started Cold Chillin’ with his manager Tyrone “Fly Ty” Williams, Pop Art released a few hoagie-sized dis bombs aimed toward those bums in Queens. “This was back in the 80s,” Asante laughs, “when Philly was the wild wild west, and those guys were coming at Marley Marl, Craig G, coming at everybody. That’s that thing we Philly cats got, and I think people appreciated that about them. We had these guys representing where we was from, and that was special too. Steady B and Cool C both represented that Philly hustle mentality.”

Steady B, who was Goodman’s nephew, was the first to sign to the label, releasing the street hard and scratch heavy “Just Call Us Def” in 1985 — the self-proclaimed “b-boy genius,” along with his homie Grand Dragon K.D. were ready to explode. “Like a nuclear attack on the hip-hop crowd.” The b-side of the 12-inch single was the equally hard “Fly Shante,” a duet with Roxanne. That same year, souped-up off the fumes of teenaged fame and professional disdain for other rappers, he dropped the LL Cool J dis “Take Your Radio.” While Steady was a fan of the Kangol wearing rapper, Pop Art encouraged dis records, knowing it would inspire fans to pay attention. Dropping his album Bring the Beat Back a year later through Jive Records, Steady B was seen as a contender.

Pop Art and Steady B were on a mission to expose the flyness of their ‘hood. Along with DJ Tat Money and Three Times Dope, an artist/label collective came together called the Hilltop Hustlers — an homage to a former West Philly street gang from the 70s. Two years later, Steady teamed-up with his Jive label-mate, hip-hop icon KRS-One, who added his Bronx boogie to a remix of Steady’s single “Serious,” a super-catchy track from his third album Let the Hustlers Play.

Philly rap superstars Jazzy Jeff & Fresh Prince in 1986 photo by David Corio

During the same time period, Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, and Salt-N-Pepa were also signed to Pop Art. Legendary Philly rapper Schoolly D says, “In the beginning of Philly rap, it was just me and MC Breeze putting out records, but what the Goodmans were doing was completely different. Pop Art wasn’t soft, but they had a way of taking the hardcore and making it radio friendly. I’d known Steady B first, back when he was MC Boob; later, we performed a few times in the Midwest together: Chicago, Detroit, Ohio.”

Glamorous Life

After appearing on several Three Times Dope records, Cool C’s first official release was the 1988 single “C Is Cool,” produced by Steady B and Goodman. The already-veteran rapper Steady wasn’t shy about sharing his expertise behind the mic as he guided Cool C through the studio process. Already close friends, Steady B and Cool C grew tighter in the lab as they worked towards the goal of being the hottest team in hip-hop.

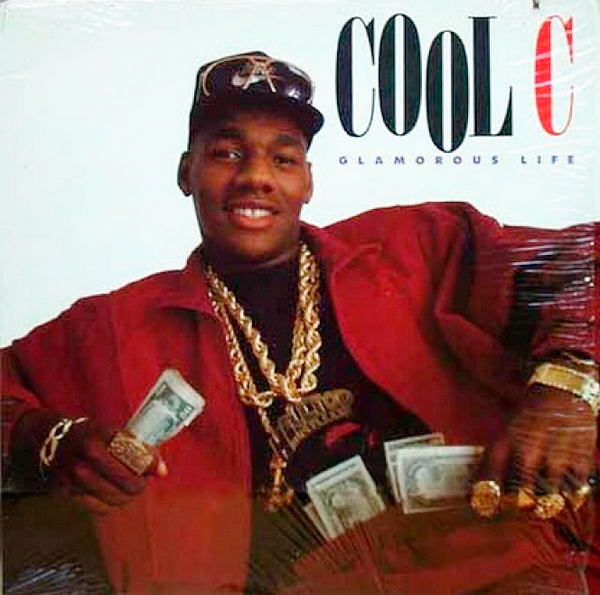

With their eyes on the prize, the following year Cool C’s infectious single “Glamorous Life,” was christened the soundtrack for the city. As the first single released from his debut album I Gotta Habit, the fun and funky track soon became a bonafide anthem. Corner boys, B-girls, break dancers and party people listening to Lady B’s “Street Beat” show on Power 99 all embraced his hedonistic braggadocio over a Bobby Byrd sample.

“That song was so awesome,” remembers the trailblazing rapper and popular radio personality Lady B. “Back then, Cool C was just a fun-loving kid who loved hip-hop. Back then, everyone in Philly was into representing their neighborhood. With me coming from West Philly, I’m an original Hilltopper. I thought the whole crew was very creative, but, when the Goodman brothers got Cool C signed to a major [Atlantic Records], that was big.”

Hiring Lionel Martin, perhaps the most popular urban music video director during that era, guaranteed the song would be heard outside of the MC’s hometown. “Although Cool C was on Atlantic, it was Lawrence Goodman who hired me to shoot the video and paid me,” Martin says from his home in California. He and his business partner Ralph McDaniels operated the pioneering urban video production company Classic Concepts. Martin adds, “Cool C was a very nice, polite young man.”

Later, Martin also crafted clips for Philly acts Boyz II Men, Da Youngstas and Jill Scott. “People always ask if the young girl in the video is Jill Scott, but I’m 99 percent sure that it isn’t. She never mentioned when we worked together.” Still, the best-kept secret about “The Glamorous Life” was that it wasn’t even shot in Philly, but in the pre-gentrification era Meat Packing District in New York City. “We put up these fake street 60th and Lansdowne signs, but we were really on the docks in Manhattan.”

Precluding Puffy’s “well-dressed playa” aesthetic by a few years, Cool C’s fashionable swag stood out on stage, in press photos and videos. Clad in fresh-pressed Adidas track suits, truck jewelry and the coolest, cleanest kicks, C was always sharp, perpetually on point.

“When it came to fashion, he was slick,” Schoolly D recalls. Seven years older than Cool C, Schoolly’s seminal 1985 single “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” originated “gangsta rap” as a genre. “I was closer to Cool C, because I used to see him in some of those after-hours spots. You know, those open-at-three-in-the-morning kind of places. We all had tailors back then who made us suits, and Cool C was into the flashy fashions. But when the 90s came, all of that changed.”

Schoolly D (Jesse Weaver) in 1986 | photo by David Corio

Things certainly had changed for the former Pop Art golden boy, whose 1990 follow-up album Life in the Ghetto scored less than impressive sales, leading to him being dropped from Atlantic. In 1993, along with Steady B’s buddy DJ Ultimate Eaze, the trio formed a crew called C.E.B and released their only album Countin’ Endless Bank on Ruffhouse Records. The group’s first single, “Get the Point,” portrayed them as gangster boogie boys maxing at the barbershop and getting locked down.

Cool C’s new shaved-head-and-prison-fatigues look was in keeping with the hard-times grimy image of Wu-Tang, Onyx and Gang Starr. But for many, the new steez just didn’t look right, it felt forced. The record sold less than 15,000 copies. Ironically, considering their future forays, “Get the Point” sampled the Honey Cone’s 1971 smash “Want Ads,” which opens with the singer wailing, “Help, I’ve been robbed… stick-up, highway robbery.”

Dog Day Afternoon

That January morning at PNC Bank, without pausing to think about past glories or future hustles, Roney’s concern instantly became all about trying to escape the approaching police officer. Crouched behind the door, he saw her blue uniform coming closer. Looking at the sturdy, round-faced woman, he didn’t see a hardworking mother with two adoring sons (Stephen and Michael, then 11 and 17), who took care of her aging parents, loved jazz and cooking. All he saw was an obstacle — a bytch in his way.

“Don’t worry, I’ll take care of her,” he yelled back, firing from his .380-caliber semi-automatic. In that moment, time froze. The single bullet exploded into Vaird’s chest, piercing her liver and heart. Her blood spilled, and she fell to floor. After exchanging gunfire with another officer, Roney frantically escaped with McGlone in a green van. Two guns were left at the scene. So was Canty. The entire incident was captured by surveillance cameras.

Officer Lauretha Vaird is the first policewoman killed in the city of Philadelphia

in REAL life it's these dudes

went from the glamorous life to

How Cool C and Steady B Robbed a Bank, Killed a Cop and Lost Their Souls

Philly rap legends Schoolly D, DJ Cash Money and others try to make sense of a tragic journey

By Michael A. Gonzales

“Philadelphia banks are not hit by takeover teams very often, and with good reason: there are few ways out.” ~Duane Swierczynski, The Wheelman

It was nearly opening time at the PNC Bank on Rising Sun Avenue in the Olney section of North Philadelphia. As early pedestrians ambled past on the cold, foggy morning of Tuesday, January 2, 1996, the bank manager entered the low-rise building alone. At the SEPTA bus stop a few feet away, a pair of construction workers casually looked on. Wearing white hardhats, the two young men appeared to be simply sipping hot coffee, puffing on Newports and talking about the forthcoming blizzard. Except they weren’t.

Instead those two men — later identified as Christopher Roney, 26, and Mark Canty, 22 — were watching every move, waiting for the opportunity to bum rush the manager and rob the bank. On the streets of Philly, Roney was more popularly known by his professional hip-hop handle, Cool C. A hit song called “Glamorous Life” had made him a local celebrity back in 1989, but a lot had changed since then.

Canty was not famous, having been recently fired from a lunch-room gig at Albert Einstein Medical Center. But rounding out the motley trio was another familiar face: Warren McGlone, 26, who acted as the heist’s wheelman. McGlone was well known as a key figure in the Philly hip-hop scene, a chubby microphone sensation who called himself Steady B.

DJ Ease, Cool C and Steady B as the short-lived C.E.B. (Countin’ Endless Bank), one year before the attempted bank robbery

Canty carried a 9 millimeter and Roney a 380-caliber semi-automatic; both knew this branch had no security guard. When PNC’s first employee arrived, they pushed their way through the building’s doorway. The manager was forced to the floor while Canty took an employee to the back to access the vault. Having pulled off successful heists previously with the rappers, Canty surely anticipated a major payday. So what if it was supposed to snow? Later that day, it’d be raining green.

However, within moments of entering the PNC Bank, the silent alarm was tripped; the pair’s clumsily thought-out plan began to go haywire.

Riding solo in patrol car #2516, female Philadelphia police officer Lauretha Vaird, a former teacher’saide who had joined the force nearly nine years prior, responded to the call. As Vaird stepped towards the bank door with her gun drawn, Canty reportedly screamed to Roney, “Here comes the heat!”

The Sound of Philadelphia

Back in the late 1980s, when hip-hop was still maturing into a commercial art form, Cool C and Steady B were ghetto superstars. They performed shows at Fairmount Park’s fabled plateau in West Philadelphia and had their 12-inches and albums stuffed into metal racks at Funk-O-Mart on Market Street. Having met when they were students at Overbrook High School, which Will Smith also attended, both were signed to local label Pop Art Records who, in turn, got them distribution and marketing deals with larger labels.

Although Steady B and Cool C were young boys, still teens when they signed on the dotted line, they were repping the region well, working as hard as their elders Lady B, Schoolly D and MC Breeze. “Those guys were the quintessential Philly rappers,” MK Asante, author of the Philly coming-of age-memoir Buck, says. “They had that Philly aggression and cockiness that just made them completely ours. Steady B came out with a song dissing LL Cool J [“I’ll Take Your Radio”], and Cool C made a track talking about the Juice Crew [“Juice Crew Dis”]. ”

Pop Art was owned by Lawrence Goodman and overseen by his brother, Dana. The label had previously released techno-funk singles by Galaxxy, disco-soul from Major Harris and early singles by Juice Crew comrades Roxanne Shanté and Biz Markie. In the 1970s, years before fictional gangster rapper-turned-music-mogul Lucious Lyon made Philadelphia rap fodder for culture vultures on Empire, Goodman had conceived the label with Ron Aikens while they served time at Graterford prison.

Located in West Philly on City Line Avenue, the small label soon became a hip-hop beacon in the brotherly love metropolis. Pop Art’s first forays into rap were Eddie D’s “Cold Cash Money” and Roxanne Shanté’s “Roxanne Revenge” in 1984. These led to a run of impactful releases from the label, which played an important role in the emerging rap marketplace. What Philadelphia International meant to soul in the 70s, Pop Art was to rap in the 80s.

“Hip-hop was still very much a singles medium back then, and Pop Art Records was more influential than they’re given credit for,” Rolling Stone writer and pop music historian Jesse Serwer explains. In 2008, he wrote about the rise and fall of the pioneering label in the “Philly Issue” of Wax Poetics. “When Marley Marl and those guys couldn’t get deals in New York City, they came to Philadelphia and signed with Pop Art. The Goodmans were street dudes, but they knew hip-hop.”

Steady B promotional photo

In 1986, after producer Marley Marl jumped ship and started Cold Chillin’ with his manager Tyrone “Fly Ty” Williams, Pop Art released a few hoagie-sized dis bombs aimed toward those bums in Queens. “This was back in the 80s,” Asante laughs, “when Philly was the wild wild west, and those guys were coming at Marley Marl, Craig G, coming at everybody. That’s that thing we Philly cats got, and I think people appreciated that about them. We had these guys representing where we was from, and that was special too. Steady B and Cool C both represented that Philly hustle mentality.”

Steady B, who was Goodman’s nephew, was the first to sign to the label, releasing the street hard and scratch heavy “Just Call Us Def” in 1985 — the self-proclaimed “b-boy genius,” along with his homie Grand Dragon K.D. were ready to explode. “Like a nuclear attack on the hip-hop crowd.” The b-side of the 12-inch single was the equally hard “Fly Shante,” a duet with Roxanne. That same year, souped-up off the fumes of teenaged fame and professional disdain for other rappers, he dropped the LL Cool J dis “Take Your Radio.” While Steady was a fan of the Kangol wearing rapper, Pop Art encouraged dis records, knowing it would inspire fans to pay attention. Dropping his album Bring the Beat Back a year later through Jive Records, Steady B was seen as a contender.

Pop Art and Steady B were on a mission to expose the flyness of their ‘hood. Along with DJ Tat Money and Three Times Dope, an artist/label collective came together called the Hilltop Hustlers — an homage to a former West Philly street gang from the 70s. Two years later, Steady teamed-up with his Jive label-mate, hip-hop icon KRS-One, who added his Bronx boogie to a remix of Steady’s single “Serious,” a super-catchy track from his third album Let the Hustlers Play.

Philly rap superstars Jazzy Jeff & Fresh Prince in 1986 photo by David Corio

During the same time period, Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, and Salt-N-Pepa were also signed to Pop Art. Legendary Philly rapper Schoolly D says, “In the beginning of Philly rap, it was just me and MC Breeze putting out records, but what the Goodmans were doing was completely different. Pop Art wasn’t soft, but they had a way of taking the hardcore and making it radio friendly. I’d known Steady B first, back when he was MC Boob; later, we performed a few times in the Midwest together: Chicago, Detroit, Ohio.”

Glamorous Life

After appearing on several Three Times Dope records, Cool C’s first official release was the 1988 single “C Is Cool,” produced by Steady B and Goodman. The already-veteran rapper Steady wasn’t shy about sharing his expertise behind the mic as he guided Cool C through the studio process. Already close friends, Steady B and Cool C grew tighter in the lab as they worked towards the goal of being the hottest team in hip-hop.

With their eyes on the prize, the following year Cool C’s infectious single “Glamorous Life,” was christened the soundtrack for the city. As the first single released from his debut album I Gotta Habit, the fun and funky track soon became a bonafide anthem. Corner boys, B-girls, break dancers and party people listening to Lady B’s “Street Beat” show on Power 99 all embraced his hedonistic braggadocio over a Bobby Byrd sample.

“That song was so awesome,” remembers the trailblazing rapper and popular radio personality Lady B. “Back then, Cool C was just a fun-loving kid who loved hip-hop. Back then, everyone in Philly was into representing their neighborhood. With me coming from West Philly, I’m an original Hilltopper. I thought the whole crew was very creative, but, when the Goodman brothers got Cool C signed to a major [Atlantic Records], that was big.”

Hiring Lionel Martin, perhaps the most popular urban music video director during that era, guaranteed the song would be heard outside of the MC’s hometown. “Although Cool C was on Atlantic, it was Lawrence Goodman who hired me to shoot the video and paid me,” Martin says from his home in California. He and his business partner Ralph McDaniels operated the pioneering urban video production company Classic Concepts. Martin adds, “Cool C was a very nice, polite young man.”

Later, Martin also crafted clips for Philly acts Boyz II Men, Da Youngstas and Jill Scott. “People always ask if the young girl in the video is Jill Scott, but I’m 99 percent sure that it isn’t. She never mentioned when we worked together.” Still, the best-kept secret about “The Glamorous Life” was that it wasn’t even shot in Philly, but in the pre-gentrification era Meat Packing District in New York City. “We put up these fake street 60th and Lansdowne signs, but we were really on the docks in Manhattan.”

Precluding Puffy’s “well-dressed playa” aesthetic by a few years, Cool C’s fashionable swag stood out on stage, in press photos and videos. Clad in fresh-pressed Adidas track suits, truck jewelry and the coolest, cleanest kicks, C was always sharp, perpetually on point.

“When it came to fashion, he was slick,” Schoolly D recalls. Seven years older than Cool C, Schoolly’s seminal 1985 single “P.S.K. What Does It Mean?” originated “gangsta rap” as a genre. “I was closer to Cool C, because I used to see him in some of those after-hours spots. You know, those open-at-three-in-the-morning kind of places. We all had tailors back then who made us suits, and Cool C was into the flashy fashions. But when the 90s came, all of that changed.”

Schoolly D (Jesse Weaver) in 1986 | photo by David Corio

Things certainly had changed for the former Pop Art golden boy, whose 1990 follow-up album Life in the Ghetto scored less than impressive sales, leading to him being dropped from Atlantic. In 1993, along with Steady B’s buddy DJ Ultimate Eaze, the trio formed a crew called C.E.B and released their only album Countin’ Endless Bank on Ruffhouse Records. The group’s first single, “Get the Point,” portrayed them as gangster boogie boys maxing at the barbershop and getting locked down.

Cool C’s new shaved-head-and-prison-fatigues look was in keeping with the hard-times grimy image of Wu-Tang, Onyx and Gang Starr. But for many, the new steez just didn’t look right, it felt forced. The record sold less than 15,000 copies. Ironically, considering their future forays, “Get the Point” sampled the Honey Cone’s 1971 smash “Want Ads,” which opens with the singer wailing, “Help, I’ve been robbed… stick-up, highway robbery.”

Dog Day Afternoon

That January morning at PNC Bank, without pausing to think about past glories or future hustles, Roney’s concern instantly became all about trying to escape the approaching police officer. Crouched behind the door, he saw her blue uniform coming closer. Looking at the sturdy, round-faced woman, he didn’t see a hardworking mother with two adoring sons (Stephen and Michael, then 11 and 17), who took care of her aging parents, loved jazz and cooking. All he saw was an obstacle — a bytch in his way.

“Don’t worry, I’ll take care of her,” he yelled back, firing from his .380-caliber semi-automatic. In that moment, time froze. The single bullet exploded into Vaird’s chest, piercing her liver and heart. Her blood spilled, and she fell to floor. After exchanging gunfire with another officer, Roney frantically escaped with McGlone in a green van. Two guns were left at the scene. So was Canty. The entire incident was captured by surveillance cameras.

Officer Lauretha Vaird is the first policewoman killed in the city of Philadelphia