Originally posted by ausar:

More recently such research has concentrated on the settlement archaeology of prehistoric periods, within a regional framework. Research, such as Hassan's in the Nagada region and Hoffman's long-term project at Hierakonpolis, has focused less on the mortuary evidence, as Petrie did, and more on subsistence strategies in the transition from early farming communities to the formation of a state…

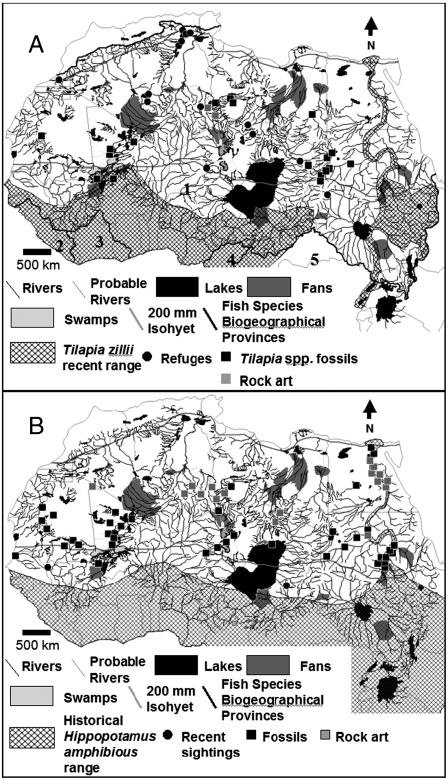

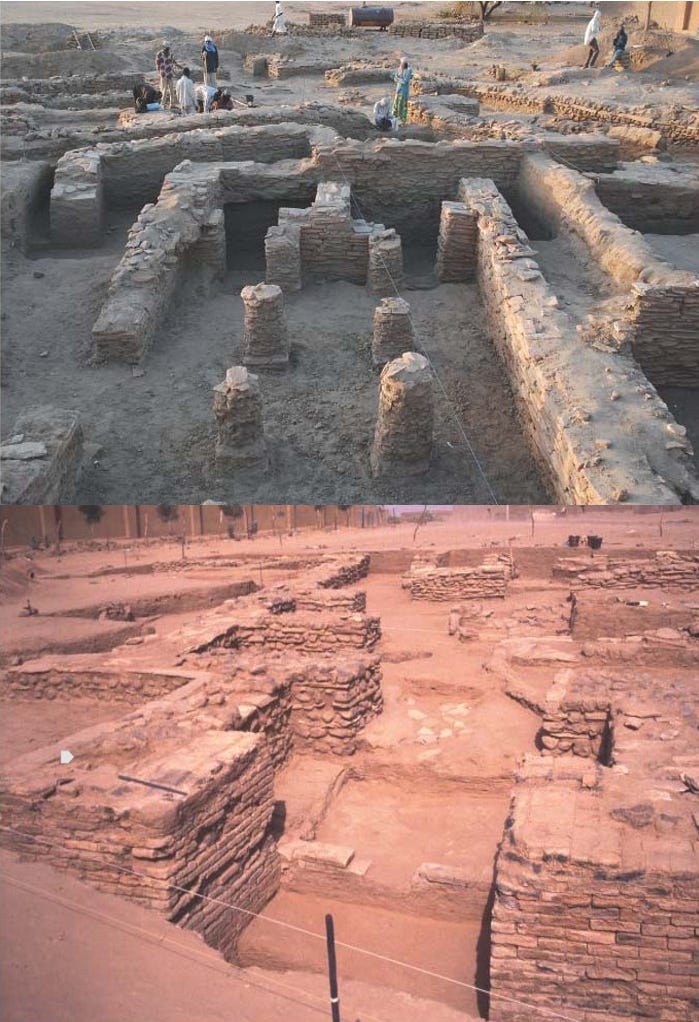

Nine more cemetery areas, dating from Nagada I through Nagada III, have also been located elsewhere in the Hierakonpolis region, and Adams and Hoffman (1987: 196, 198) estimate there were several thousand Predynastic graves in the region. One cemetery area (Locality 6), located 2.5km up the Great Wadi, contained more than 2000 Nagada I-II burials, and large Nagada "Protodynastic" tombs, up to 22.75 sq m. in floor area (Adams and Hoffman 1987: 196, 202). Burials of elephants, hippopotami, crocodiles, baboons, cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs have also been excavated SW of a stone-cut tomb in the western part of this cemetery (Hoffman 1983: 50). One of the largest tombs, tomb 11, though looted, retained fragments of beads in carnelian, garnet, turquoise, faience, gold, and silver. Also in this tomb were artifacts carved in lapis lazuli and ivory, obsidian and crystal blades, "Protodynastic" pottery, and a wooden bed with carved bulls' feet (Adams and Hoffman 1987: 178).

Evidence of postholes demonstrates that superstructures once covered some of the large tombs in Locality 6, and these tombs were surrounded by fences (Hoffman 1983: 49). Possibly a kind of perishable structure was built over some of the tombs, similar to the house structures Hoffman excavated. If so, then this may be the earliest association of large elite tombs with a superstructure that symbolized a house/shrine for the deceased. Hoffman (1983: 49) states that the Locality 6 tombs belonged to the Protodynastic rulers of Hierakonpolis, and speculates that the largest tomb there was that of King Scorpion. Hence, the Locality 6 tombs suggest that in the Nagada III period at Hierakonpolis there was a new location for the highest status burials, replacing the earlier elite cemetery where the Decorated Tomb (Nagada II) was located.

The best known Predynastic site in the Fayum region is the cemetery at Gerza, from which the term Gerzean (Nagada II) is derived. The site is located on the west bank, about 7 km NE of Medum. compared to the major cemeteries in Upper Egypt this was a small cemetery, with only 288 burials, a high percentage of them undisturbed; 198 of these were of adults and 51 were of infants or children (Petrie, Wainwright and MacKay 1912: 5). The ceramics listed for these burials are typical of the Nagada II period and include the Wavy-handled and Decorated classes. Beads, stone vases, zoomorphic slate palettes, flint knives, and other Nagada II artifacts, some of which were elite goods probably imported from the south, were also found in these graves. (No mention is made by Petrie of a Predynastic settlement at Gerza)…

Harageh, SE of the village of Lahun, was excavated in 1913-1914 by Reginald Engelbach, and consists of two Predynastic cemeteries, G and H. Engelbach (1923: 2) places the date for both cemeteries between S.D. 50-60, based on the pottery in the burials, which includes the Decorated class. Many of the graves were robbed, and there were no slate palettes and very few beads. Wavy-handled class pottery was found only in Cemetery H (Engelbach 1923: 7). Given its low number of burials and relatively few high status grave goods, Harageh was probably only a small Predynastic community with little social differentiation…

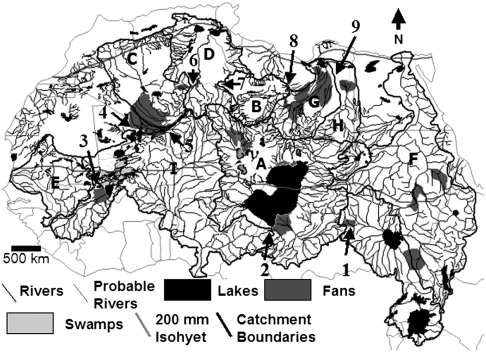

Some pottery from Harageh Cemetery H, which Engelbach thought was much later (Pan Graves?), resembles Lower Egyptian Predynastic pottery found at Sedment (Kaiser 1987: 121-122; Williams 1982: 220). The presence of pottery of Lower Egyptian origin at a site in this region is also attested at the cemetery of es-Saff on the east bank opposite Gerza (Habachi and Kaiser 1985: 46). From this evidence it seems likely that the Fayum region was where the two Predynastic cultures of Upper and Lower Egypt first came into contact…

Ancient Egypt is one of the earliest examples of (primary) state formation, and Predynastic data should elucidate general processes which may be applicable to other cases of state formation. but we only have a partial understanding of the Predynastic, based on different types of data in the north and south. Possibly new and forthcoming evidence from the Delta will provide information on the processes of state formation and unification there, but in the south there is the problem of so many missing settlement data, which are needed in order to make theoretical generalizations.

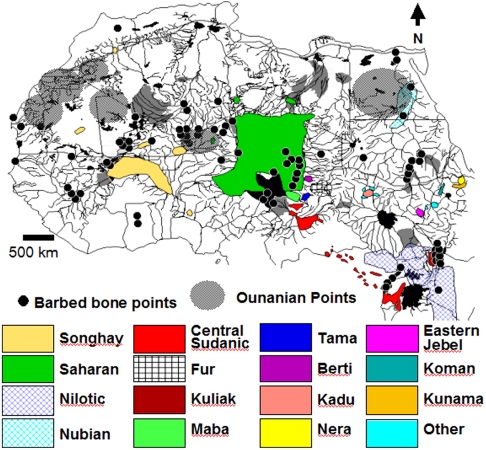

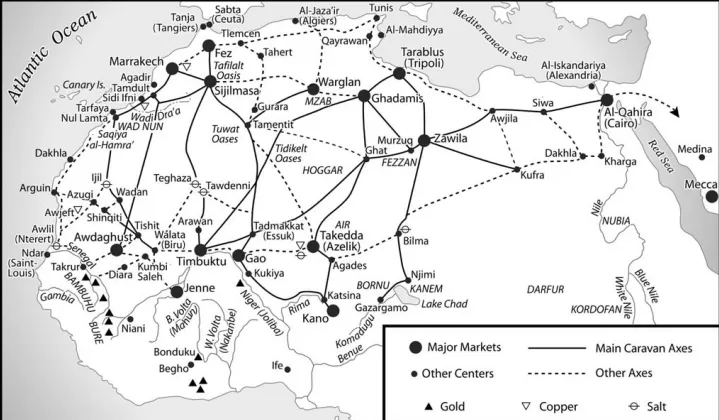

Despite the problem of poorer settlement evidence in Upper Egypt, the emerging picture of Egypt in the 4th millennium B.C. is of two different material cultures with different belief systems: the Predynastic Naqada culture of Upper Egypt and the Maadi culture of Lower Egypt. Archaeological evidence in Lower Egypt consists mainly of settlements, with very simple burials in cemeteries, and suggests a culture different from that of Upper Egypt, where cemeteries with elaborate burials are found. While the rich grave goods in several major cemeteries in Upper Egypt represent the acquired wealth of higher social strata, the economic sources of this wealth cannot be satisfactorily determined because there are so few settlement data, though the larger cemeteries were probably associated with centers of craft production. Trade and exchange of finished goods and luxury materials from the Eastern and Western Deserts and Nubia would also have taken place in such centers. In Lower Egypt, however, settlement data permit a broader reconstruction of the prehistoric economy, which at present does not suggest any great socio-economic complexity.

Differentiation in the Predynastic cemeteries of Upper Egypt (but not Lower Egypt) is symbolic of status display and rivalry (Trigger 1987: 60), which probably represent the earliest processes of competition and the aggrandizement of local polities in Egypt. The importation of exotic materials for craft goods found in burials may have become a political strategy, and the control of prestige goods would have reinforced the position of a chief among his supporters.

Evidence of extensive contact between Upper Egypt and Nubia in later Predynastic times is indicative f the increasing interest in prestige goods. Numerous Nagada culture trade goods have been found at most A-Group sites in Nubia between Kubania in the north and Saras in the south. These include jars that may have contained beer or wine, and Wavy-handled jars. Other Nagada pottery classes are found at A-Group sites, as are Naqada craft goods: copper tools, stone vessels and palettes, linen, and beads of stone and faience (Nordstrom 1972: 24; Smith 1991: 108).

A-group burials are very similar to graves of the Nagada culture, but inspite of similar burials and grave goods Trigger (1976: 33) thinks that the A-Group developed from an indigenous population that was in contact with Upper Egypt and much influenced by Nagada culture. A-Group wares are distinctive, and few A-Group artifacts have been found in Upper Egyptian graves, suggesting that the A-Group acted as middlemen in a trading network with Upper Egypt (Trigger 1976: 39). Luxury materials, such as ivory, ebony, incense, and exotic animal skins, all greatly desired in Dynastic times as well, came from father south and passed through Nubia. Kaiser (1957: 74, fig. 26), however, interprets the A-Group evidence as a "colonial" penetration into Lower Nubia to exploit trade and raw materials (Needler 1984: 29).

In his analysis of the Classic A-Group (contemporaneous with Nagada III) "royal" Cemetery L at Qustal, Williams (1986: 177) proposes another theory: that this cemetery represents Nubian rulers who were responsible for unifying Egypt and founding the early Egyptian state. The A-Group n Nubia, though, appears to have been a separate culture from that of Predynastic Upper Egypt, and the model that may best explain the archaeological evidence is one of accelerated contact between the two regions in later Predynastic times. That the material culture of the Nagada culture was later found in northern Egypt (with no Nubian elements) would seem to argue against William's theory of a Nubian origin for the Early Dynastic state in Egypt.

The unification of Egypt took place in late Predynastic times, but the processes involved in this major transition to the Dynastic state are poorly understood. What is truly unique about this state is the integration of rule over an extensive geographic region, in contrast to the other contemporaneous Near Eastern polities in Nubia, Mesopotamia, Palestine and the Levant. Present evidence suggests that the state which emerged by the First Dynasty had its roots in the Nagada culture of Upper Egypt, where grave types, pottery, and artifacts demonstrate an evolution of form from the Predynastic to the First Dynasty. This cannot be demonstrated in Upper Egypt.

Hierarchical society with much social and economic differentiation, as symbolized in the Nagada II cemeteries of Upper Egypt, does not seem to have been present, then, in Lower Egypt, a fact which also supports an Upper Egyptian origin for the unified state. thus archaeological evidence cannot support the earlier theories that the founders of Egyptian civilization were an invading Dynastic race, from the East (Petrie 1920: 49, 1939: 77; Emery 1967: 38), or from the south, in Nubia (Williams 1986: 177).