After 50 years, ‘Vibration Cooking’ still resonates

by Cassie Owens, Posted:

June 18, 2020

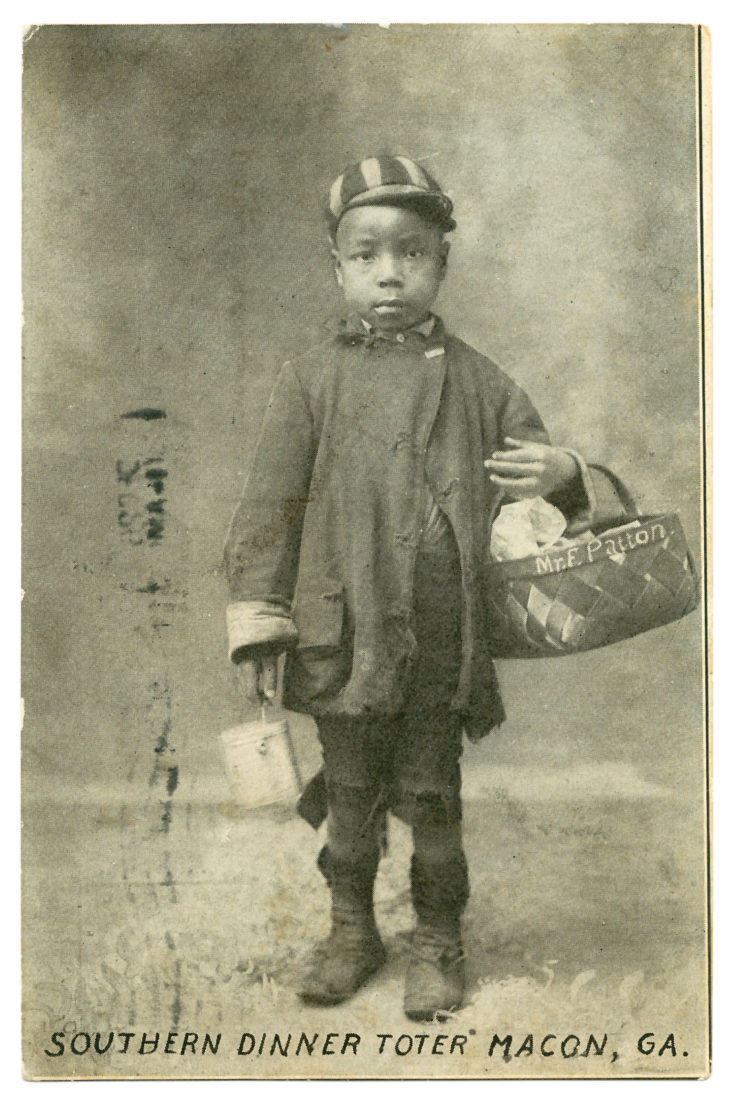

Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl: The Lifestory of Vertamae-Smart Grosvenor.

The three-story rowhouse on Erdman Street where Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor’s family lived doesn’t exist anymore. It’s been razed and replaced. The Smarts had been making a new life there, among the hundreds of thousands of Southerners who moved to Philadelphia during the Great Migration.

“Wasn’t but seven families on the street, and five of them from South Carolina," wrote Smart-Grosvenor, who died in 2016, in her seminal cookbook,

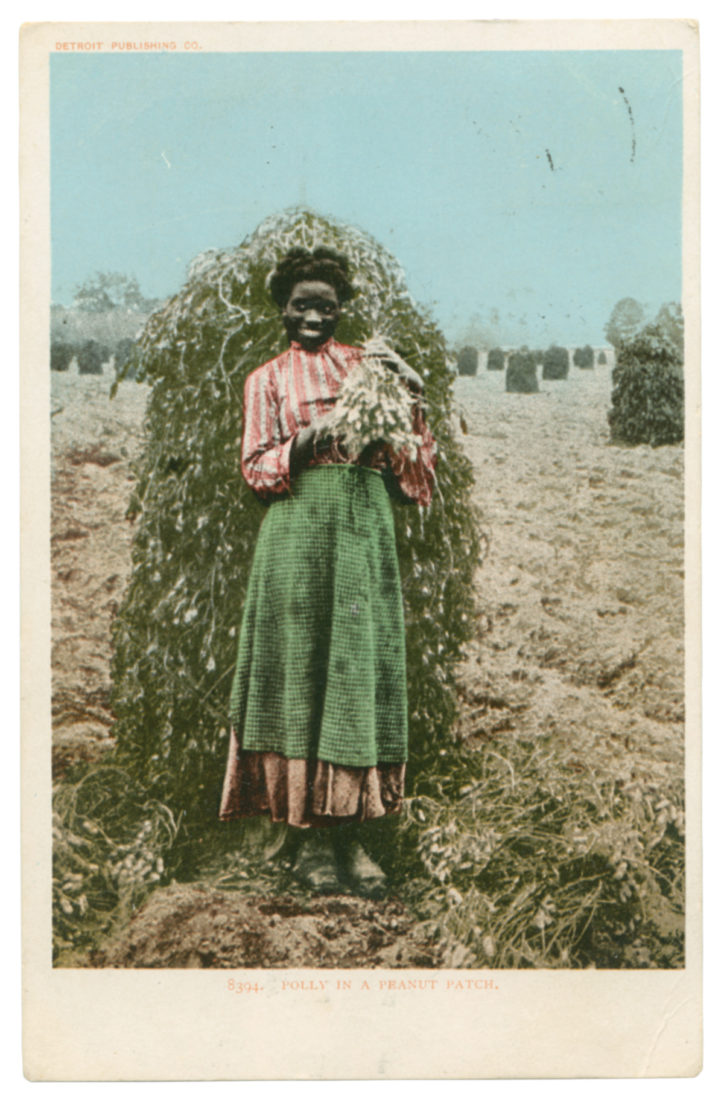

Vibration Cooking: Or, The Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl. Many of her recipes came from the South Carolina Lowcountry.

“Whenever Daddy went crabbing it was a real treat. We would have enough crabs for all of Erdman street. We would boil the crabs down in a No. 2 tub and eat for days, adding a quart of beer to the water — sometimes.”

The Smarts had followed Vertamae’s grandmother, who had settled in North Philly. As Isabel Wilkerson explained in her 2010 book on the Great Migration,

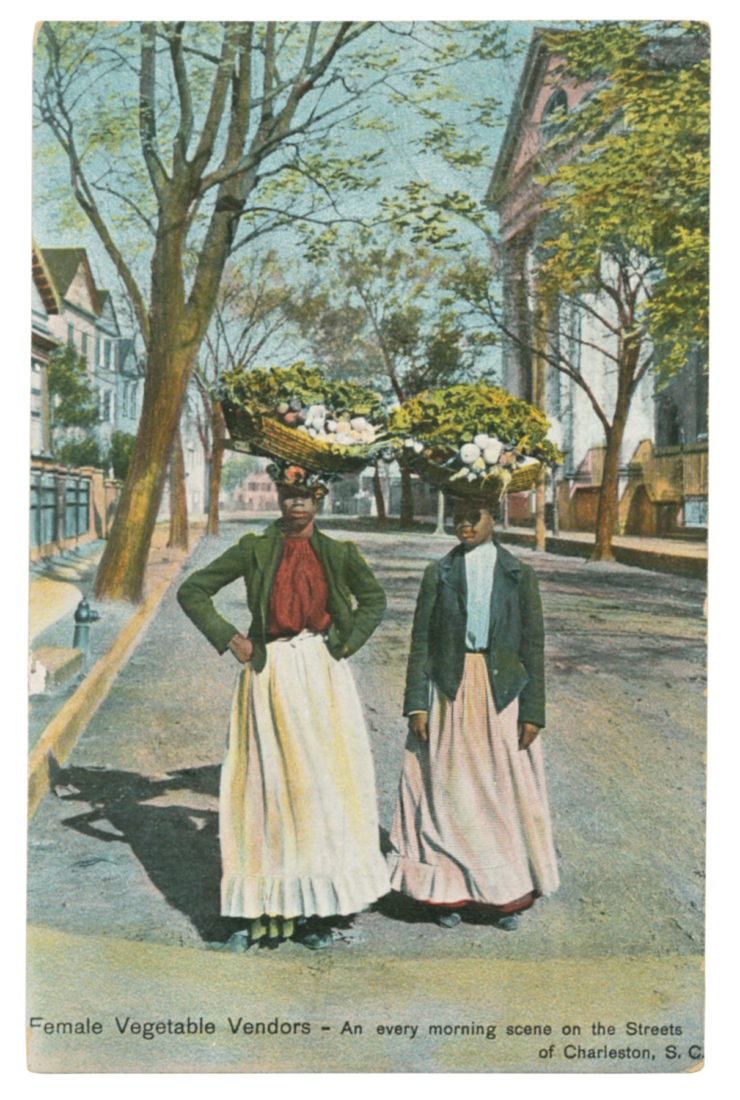

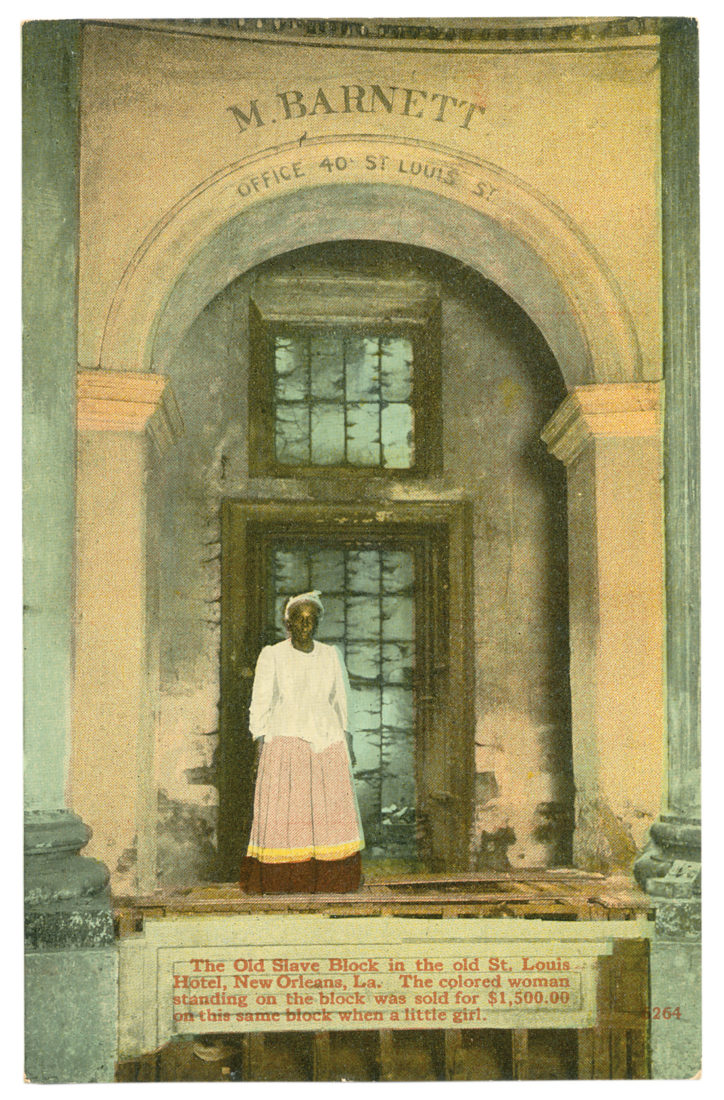

The Warmth of Other Suns, Southerners often followed people they knew, resulting in churches, communities, and cities of folk who called the same areas home. Philadelphia and New York were common destinations for Gullah-Geechee people from the coasts of South Carolina and Georgia, the descendants of enslaved Africans who are deeply influenced by West African cultures.

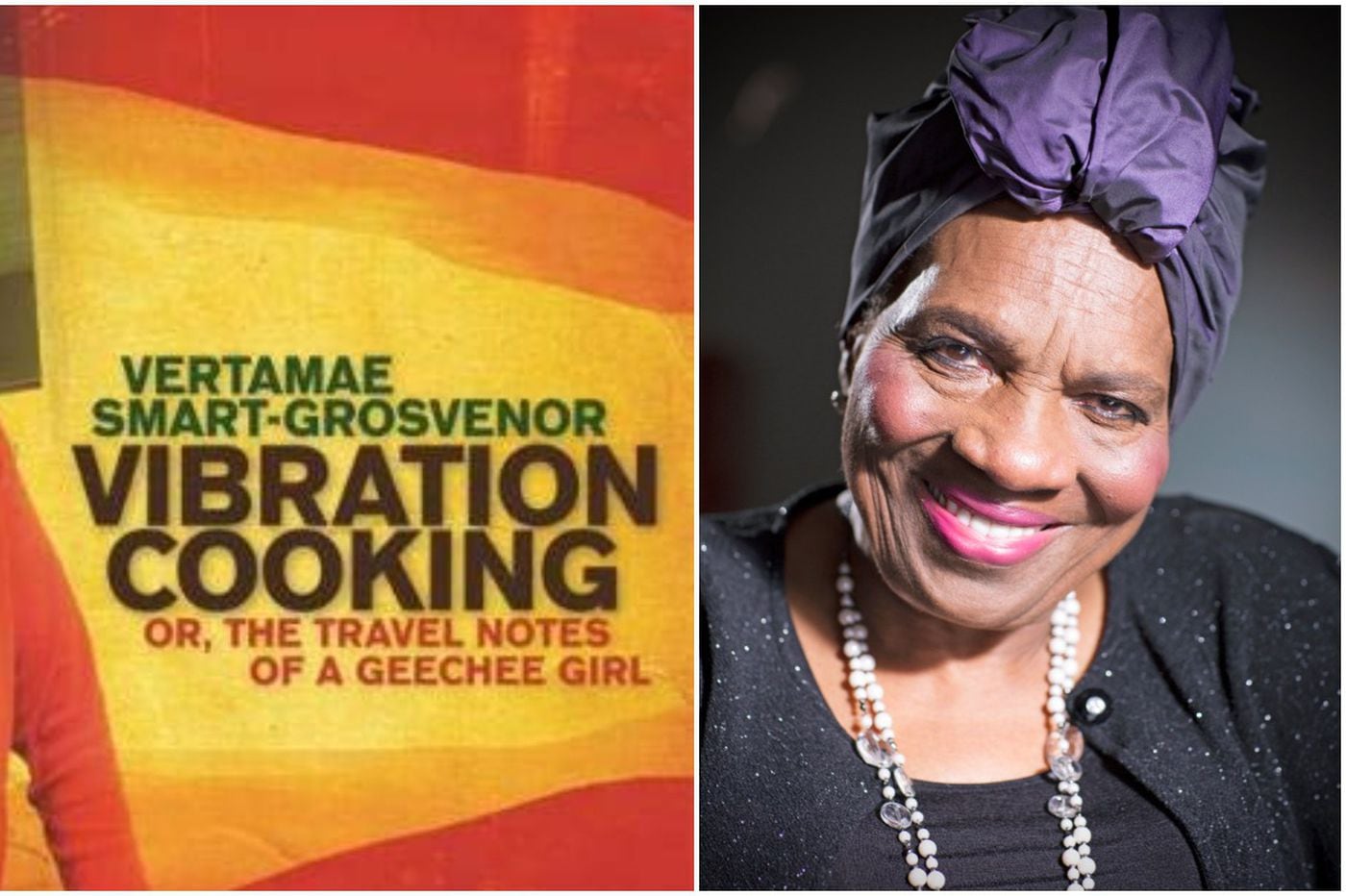

Vibration Cooking was published in 1970.

The title for her book was bold. In 1970, many Americans were unfamiliar with Gullah-Geechee culture, which was stereotyped as country and backward. Even chef Valerie Erwin, who owned Geechee Girl Cafe in Mount Airy until it closed in 2015, said some diners were convinced that the name Geechee is pejorative. Smart-Grosvenor still put her that part of her identity front and center.

The memory of sharing crabs on the block, like much of the book, reads more like what you might come across in food writing today, on sites like Food 52 or in the comments section of New York Times Cooking, rather than in 1970 when it was first published. Fifty years later,

Vibration Cooking is a book that moves beyond memories, and gives a glimpse of how black migrants lived and ate in postwar Philadelphia.

Smart-Grosvenor called herself a culinary griot. Along with her cookbooks and catering, Smart-Grosvenor was an actress, a researcher of black domestic workers, and a longtime NPR contributor. She had a lot of famous friends, including Maya Angelou, Nina Simone, and James Baldwin, and she often fed the brightest of the black literati.

Kali Grosvenor, Smart-Grosvenor’s elder daughter, has been revisiting

Vibration Cooking as she researches details on her family’s life in Philadelphia.

“It strikes me that all the places we can trace her to are gone or vanished,” Kali Grosvenor said. Francisville, an increasingly popular name for Smart-Grosvenor’s part of town, has been called

“the front lines of gentrification.”

“She was a part of all these different movements,” said Julie Dash, director of the classic 1991 film

Daughters of the Dust who is studying Smart-Grosvenor’s life for a forthcoming documentary. Smart-Grosvenor, a member of the Beat Generation, was involved in the Black Arts Movement, Black Cinema Movement, and Black Power Movement, too, Dash said. “Arts, culture, politics — all of these things coalesced through her life.”

Vibration Cooking was never simply about Southern food, Dash explained.

In fact, the “soul food” label was one she resisted. In the introduction of the 1992 edition of

Vibration Cooking, Smart-Grosvenor clarified that she made black foods because she loved them, not because of any “culinary limitations.” “I would explain that my kitchen was the world, ” she wrote.

The book journeys through Philly, Paris, New York, and Rome, the Caribbean and the Congo. She writes about the friends who taught her recipes

, the artists in her community, and the gatherings where it all came together. She shares commentaries on racist attitudes, turning a negative response to the African attire she wore into opportunity to consider how Europeans brought foods to the New World that they themselves had taken from other places. (“Now, if a squash and a potato and a duck and a pepper can grow and look like their ancestors, I know damn well that I can walk around dressed like mine.”)

“She was doing Afro-Atlantic foodways based upon the West African traditions that were still in use in the Lowcountry," Dash said. "The rice and the seafoods, and the shellfish and all that. But people didn’t understand that. She was so before her time that it wasn’t funny.”

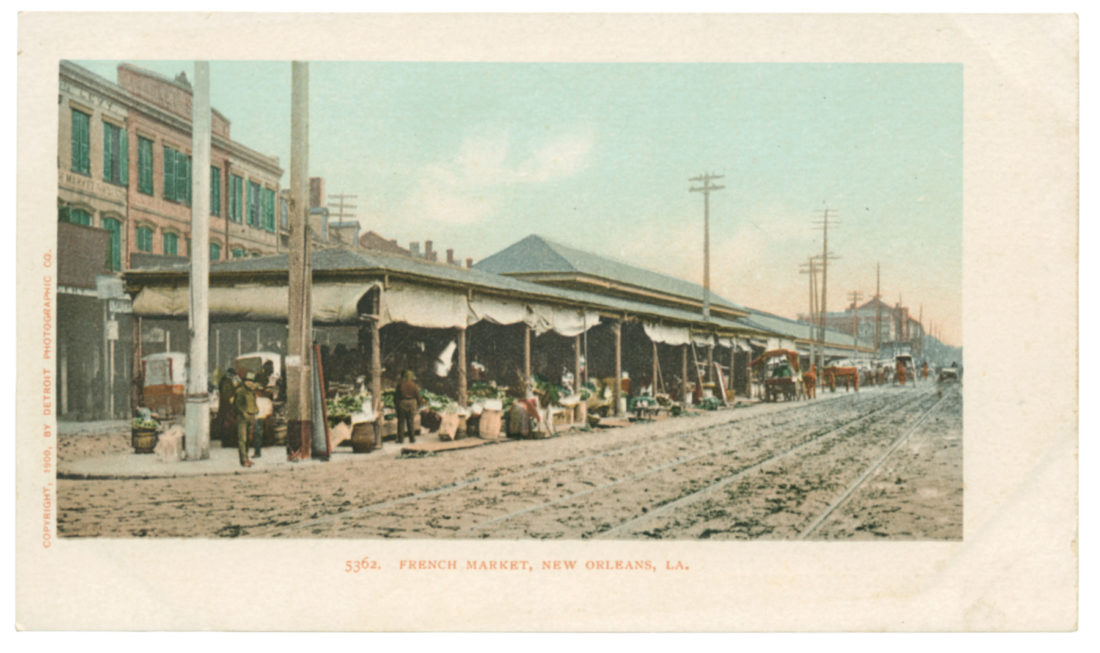

The recipes connected to Philadelphia, many of them in an early chapter that includes fried oysters, catfish stew, fried soft shell crab, crab cakes. Smart-Grosvenor named her version of fried chicken — which requires soaking the bird in a mix of milk and eggs for three hours — after arts scholar Larry Neal because she made it that way for him, she explained, “so we could talk.”

Neal was among the friends Smart-Grosvenor would meet for espresso as a budding beatnik. They’d spend time at a Rittenhouse cafe called the Artists’ Hut.

“I cook by vibration. I can tell by the look and smell of it,” she wrote in

Vibration Cooking, explaining a lack of measurements.

Ashbell McElveen, a culinary historian and founder of the James Hemings Society, finds kinship in this approach.

“When you talk about

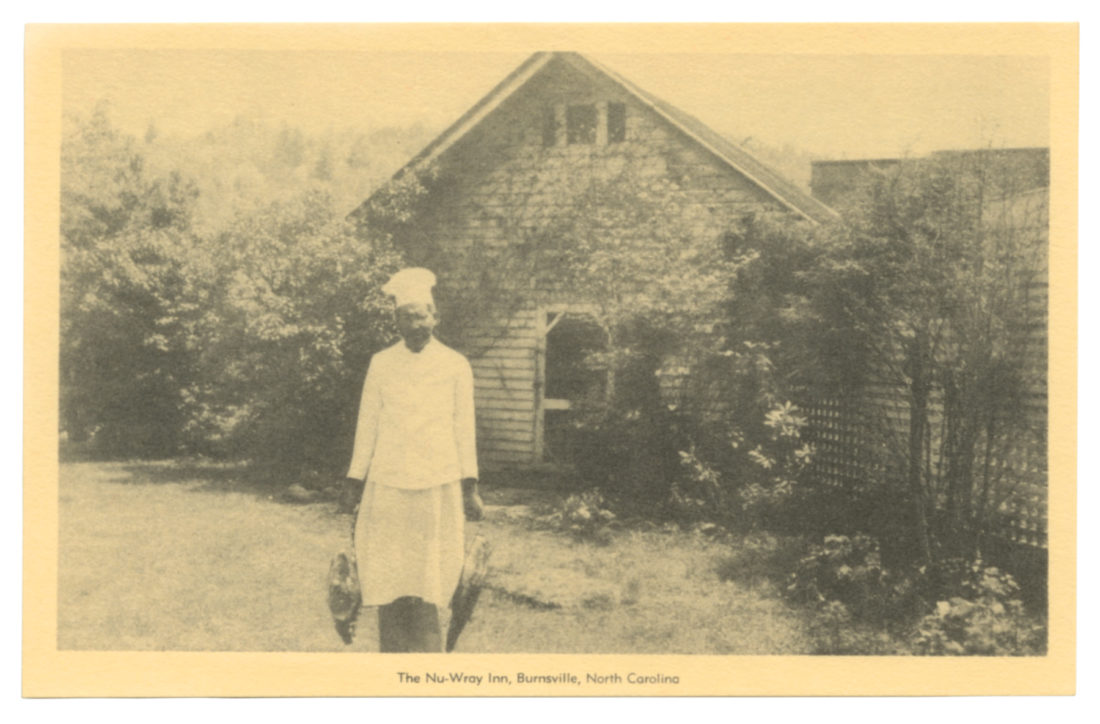

Vibration Cooking, for her it was all those cues that you learn when you didn’t have a recipe, you had the time,” said McElveen, who once entertained Smart-Grosvenor as a dinner guest. “How long is that going to take in the fireplace? Do I have to rake this over to the coals and leave this on the slag for a while? All of these adjustments that actually inhabits the life of a good, seasoned cook. And that’s the heritage of African Americans cooking in the South. It is not a recipe, necessarily, it is a way that we actually passed on knowledge.”

African Americans, McElveen said, “have always been situational cooks,” adapting traditions to the (new) locations where they are. The cuisines that enslaved chefs created, the foodways of the Great Migration, the black culinary traditions of Philadelphia, and

Vibration Cooking, he explained, are all examples of this.

Kali Grosvenor remembers being able to tell her mother’s mood by the way she was cooking. She was an artist who stated plainly that food was her medium. That her food could survive, even if many of the places that shaped her did not, Grosvenor said, is “the point of the book.