UpAndComing

Veteran

Or should I say DURING slavery

https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/L_Schweninger_Black_1989.pdf

https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/black-leaders-during-reconstruction

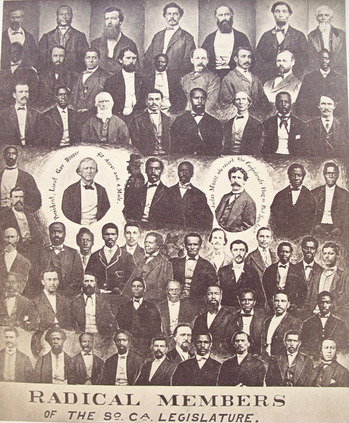

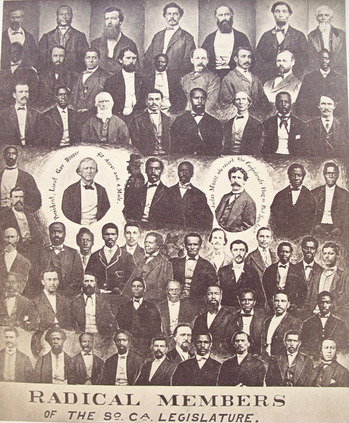

Picture titled "Radical Members of the South Carolina Legislature", 1868

The Emancipation Proclamation didn't "free" Black people. It was to capitalize on the Black Economic Enterprise that was rising, and also to weaken it

Interesting

https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/L_Schweninger_Black_1989.pdf

As a result, despite the anti-free black sentiment among some whites, free Negroes in the region entered a variety of business pursuits. In towns and cities, they became builders, mechanics, tradesmen, grocers, restaurateurs, tailors, merchants, and barbers. Even during the American Revolution, a small group of skilled artisans and craftsmen had emerged in Charleston, South Carolina. By the 1790s, several among them had built up thriving businesses, especially in the furniture and building trades.(20) House builder and carpenter James Mitchell, who for many years lived above his shop, had become so prosperous by 1797 that he sought to rent a six-room house with stables and out-buildings. A Place in the suburbs, with a little Garden," he explained in a local newspaper, "would be preferred."(21)

Under the criteria cited previously, the number of free blacks engaged in business nearly doubled during the 1850s (from 575 to 1,048) (see Table 1). Although the number of large farmers and planters fell in some sections of the Lower South, including several Louisiana parishes, in other sections free persons of color expanded their holdings and began new business operations. There was also a surge into the entrepreneurial class during the 1850s among free women of color, who opened boarding and lodging houses, seamstress shops, and laundry businesses. AD the business occupational categories-artisans usually engaged in business blacksmiths, cabinet makers, shoemakers, tailors, etc.); small-scale manufacturers (brickmakers, cigarmakers, sugar manufacturers, etc.); service businesses (barbers, brokers, livery keepers, "landlords," realtors); retailers (butchers, grocers, lumber merchants, dry goods merchants, etc.); and artisans, seamstresses, and laundresses with at least $1,000 in total estate holdings or farmers and planters with at least $2,000-grew between 1850 and 1860. Estimated pecuniary strength also rose, though not enough to keep pace with inflation or rising land and property values. By 1860, the mean total estate of Lower South blacks engaged in business stood at $7,000; the median stood at $2,300 (see Table 2). The figures suggest that those at the top of the business hierarchy were to some extent protected from the racial turmoil confronting other free blacks during the tumultuous decade before the Civil War.(56)

https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/black-leaders-during-reconstruction

Blacks made up the overwhelming majority of southern Republican voters, forming a coalition with “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags” (derogatory terms referring to recent arrivals from the North and southern white Republicans, respectively). A total of 265 African-American delegates were elected, more than 100 of whom had been born into slavery. Almost half of the elected black delegates served in South Carolina and Louisiana, where blacks had the longest history of political organization; in most other states, African Americans were underrepresented compared to their population. In all, 16 African Americans served in the U.S. Congress during Reconstruction; more than 600 more were elected to the state legislatures, and hundreds more held local offices across the South.

Picture titled "Radical Members of the South Carolina Legislature", 1868

The Emancipation Proclamation didn't "free" Black people. It was to capitalize on the Black Economic Enterprise that was rising, and also to weaken it

Interesting

Same shyt.

Same shyt. what else is new learning about the history of the tyrannical white man who hated us from the very beginning???

what else is new learning about the history of the tyrannical white man who hated us from the very beginning???