You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

KKK formed because Black Economic power was rising up "too quickly" after Slavery

- Thread starter UpAndComing

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Family Lives Matter

#FLM

How is this news

It started with the Compromise of 1877. All Black people, especially the “get out and vote!” crowd need to understand how the government held up the presidential election and then used the electoral college to steal that election after the deal was made to remove the federal troops that had been protecting southern Blacks in the south. That’s when the kkk and other white nationalist groups really began to rise throughout the south.

a bunch of punk ass bytches. Just like when i see them in person. For some of you younger brehs, know a lot of these cowards will stand behind u in line at the store imagining how they can field-dress you like a doe. Stay vigilant fellas.

Kyle C. Barker

Migos VERZUZ Mahalia Jackson

Klan formed because 'White' people didn't want Black folks to have any rights during (and after) Reconstruction.

Pretty much this. There were a lot of black towns that got burned down in the late 1890s because they were too self sufficient and prosperous. A few in the Carolinas and Northern Florida from what I can recall.

LiveFromLondon

Superstar

Them undercover white liberals masquerading as black bout to come at you brehI try to tell people this all the time in regards to emancipation and integration but that thorough public school brainwashing is real.

Not only did they trick black people into letting white people infiltrate and sabotage any attempts at self sufficiency, they created a "white savior" complex that still exists to this day in most black people.

Pretty much this. There were a lot of black towns that got burned down in the late 1890s because they were too self sufficient and prosperous. A few in the Carolinas and Northern Florida from what I can recall.

I was just talking about this with my wife. When we start to gain capital, that is the threat. We can act rap about getting liquid cash and toss it at hoes (make it rain) all day. But when we actually start making power moves for our future generations is when it becomes a problem to them

UpAndComing

Veteran

what else is new learning about the history of the tyrannical white man who hated us from the very beginning???

Because it turns the whole Integration story upside on its head

That black people "downtrodden and powerless" and "just accepted being in bondage"

Which was untrue from the constant slave revolts, and the huge number of Black people BEFORE slavery ended who had thriving business and ownership

Makes the "Lincoln saved us" with the Emancipation Proclamation as a total lie. Black people forced the Proclamation, US did it to capitalize on the Black Economic power structure. We were better in Segregation. Whites used integration to dilute Black economic resources

xoxodede

Superstar

Or should I say DURING slavery

https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/uncg/f/L_Schweninger_Black_1989.pdf

https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/black-leaders-during-reconstruction

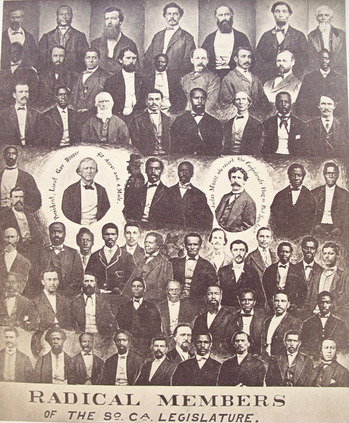

Picture titled "Radical Members of the South Carolina Legislature", 1868

The Emancipation Proclamation didn't "free" Black people. It was to capitalize on the Black Economic Enterprise that was rising, and also to weaken it

Interesting

The Emancipation Proclamation didn't "free" Black people. It was to capitalize on the Black Economic Enterprise that was rising, and also to weaken it.

What "Black Economic Enterprise" was rising before Emancipation Proclamation? Where and what industries was this Black Economic Enterprise rising?

Especially when 4 Million Black people of the 4.5 Million Black People in America were enslaved in the South.

No, it didn't "free" the majority of Black people in the South -- cause they had no where to go -- nor anyone to hire them. Many were forced into contracts --- and killed when they refused.

- Freedman killed for refusing to sign a contract, Sumter Co., May. Freedman killed in Butler Co., clubbed, April.

- May 29 - Colored man killed by Lucian Jones for refusing to sign contract, in upper part of Sumter Co.

- May 29 - Richard dikk's wife beaten with club by her employer. Richard remonstrated - in the night was taken from his house and whipped nearly to death with a buggy trace by son of the employer & two others.

- June 1866 - Freedman shot while at his usual work by his employer for threatening to report his abusive conduct to the authorities of the Bureau - Mobile.

- July 16 - Mrs. Prus beat Eve & her children. Henry Calloway beat freedwoman Nancy with buck, wounding her severely in the head. J. Howard & nephew beat & shot at Frank. Jno. Black attempted to kill Jim Sneethen with an axe. Jack McLeonard whipped his freedwoman mercilessly. Lee Davidson tied freedwoman up by wrists & beat her severely. Frank Pinkston cutting freedman Alfred with knife. Louisa's husband murdered by unknown white man.

Whites were extra salty and demonic because they were now "free" -- and had to pay them. Many of them still didn't -- and killed them or beat them when they asked for their pay.

Y'all should read letters, correspondences, books, newpaper articles etc from important Black people from the reconstruction era to the 50's and you'll see that Garvey was a drop in the bucket compared to all the Black men and women out there talking just like him and getting similar levels of accomplishments done. It's fascinating.

this is low-key why I kinda side eye a lot of overt marxism....black people have been trying to get that bag for A LONNNNNG TIMEFacts

All black people should be aware of the period directly after the civil war called reconstruction

A whole bunch of fukk shyt happened in that time period

Iirc that's when labor unions were created so that white people could present a unified front to employers because the newly freed slaves were out competing them in both skilled and unskilled labor

@wire28 @Return to Forever @ezrathegreat @Jello Biafra @humble forever @Darth Nubian @Dameon Farrow @General Bravo III @BigMoneyGrip @hashmander @Call Me James @VR Tripper @Iceson Beckford @dongameister @Soymuscle Mike @BaileyPark31 @Lucky_Lefty @johnedwarduado @Armchair Militant

The Fade

I don’t argue with niqqas on the Internet anymore

It's also funny how cacs worship Capitalism in their holy trinity along with guns..

But History showed that pure capitalism was beating they ass til they had government help..

Comical

They had to run to the Klan in the south cause the Viets were killing the Crawfish game too.

But History showed that pure capitalism was beating they ass til they had government help..

Comical

They had to run to the Klan in the south cause the Viets were killing the Crawfish game too.

xoxodede

Superstar

Southern whites were very divided in 1867. Some of them said, "We've got to go out. We've got to mobilize ourselves. We've got to go out and out-vote these people." Most Southern states had white majorities. So even if all blacks voted, if the whites could unite against them, they could still keep control. In other places they said, "No, this is a travesty of democracy. We're just going to boycott. We're going to have nothing to do with it. Let them go ahead and they'll do all sorts of crazy things, and they'll discredit themselves." And then there were some white Southern leaders who said, "Well, we've got to go out and appeal to them. We've got to get them to vote for us. They don't have to vote Republican." And some of them actually went and gave speeches to black gatherings, and basically said, "Look, we were masters... You understand how good slavery was. You should vote for us." But those speeches didn't seem to get a lot of support. So there was a lot of uncertainty and political division within the white population in 1867, about how to respond to this completely new situation.From 1868 through the early 1870s the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) functioned as a loosely organized group of political and social terrorists. The Klan's goals included the political defeat of the Republican Party and the maintenance of absolute white supremacy in response to newly gained civil and political rights by southern blacks after the Civil War (1861-65). They were more successful in achieving their political goals than they were with their social goals during the Reconstruction era.

KKK formed because they did not want newly freedmen -- or Black people in general anywhere in the U.S. to have rights. They didn't want them to vote, be employed, go to school, run a business -- anything. In Reconstruction, the KKK served as a terrorism group to stop Black people from voting. Political terrorism.

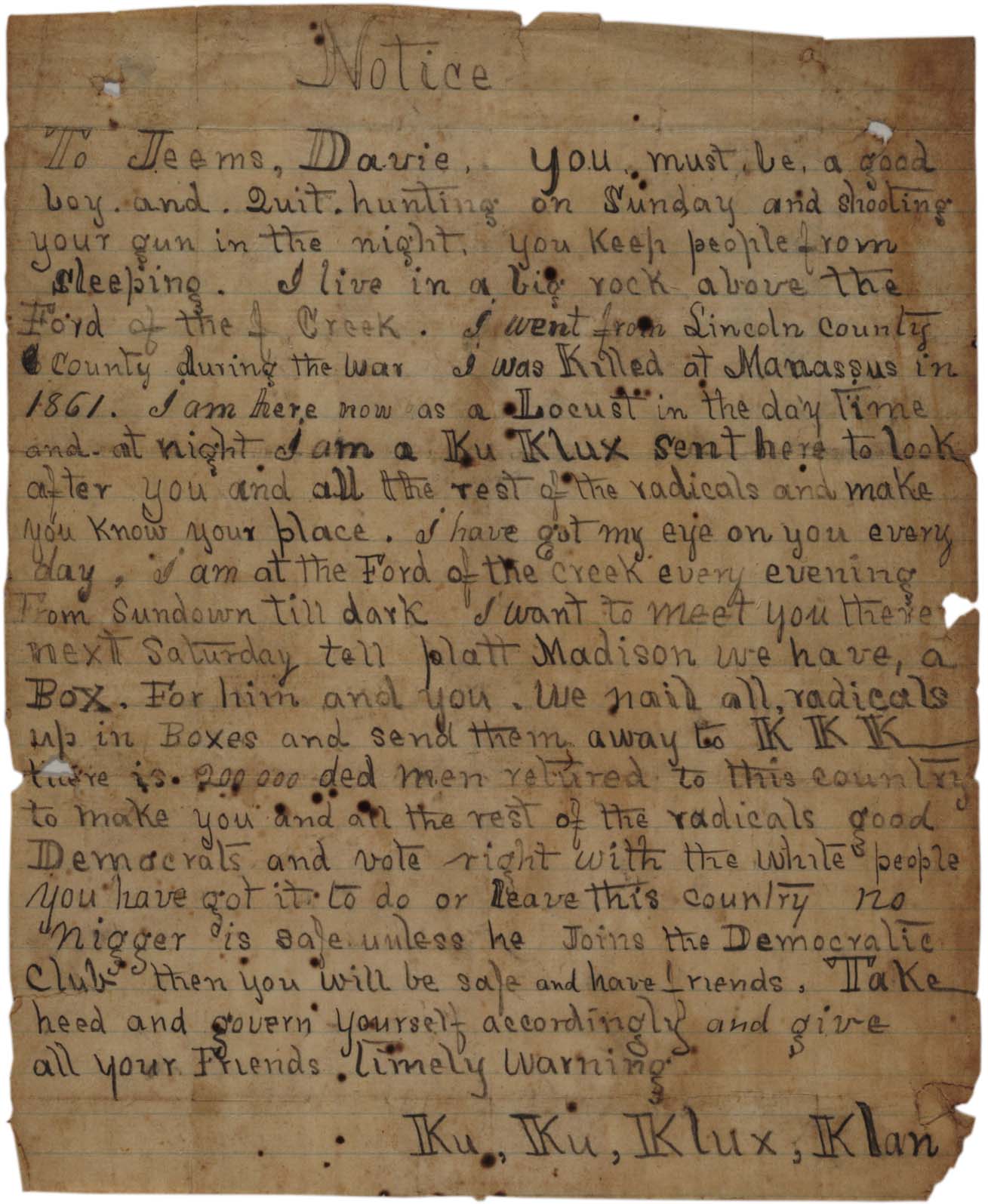

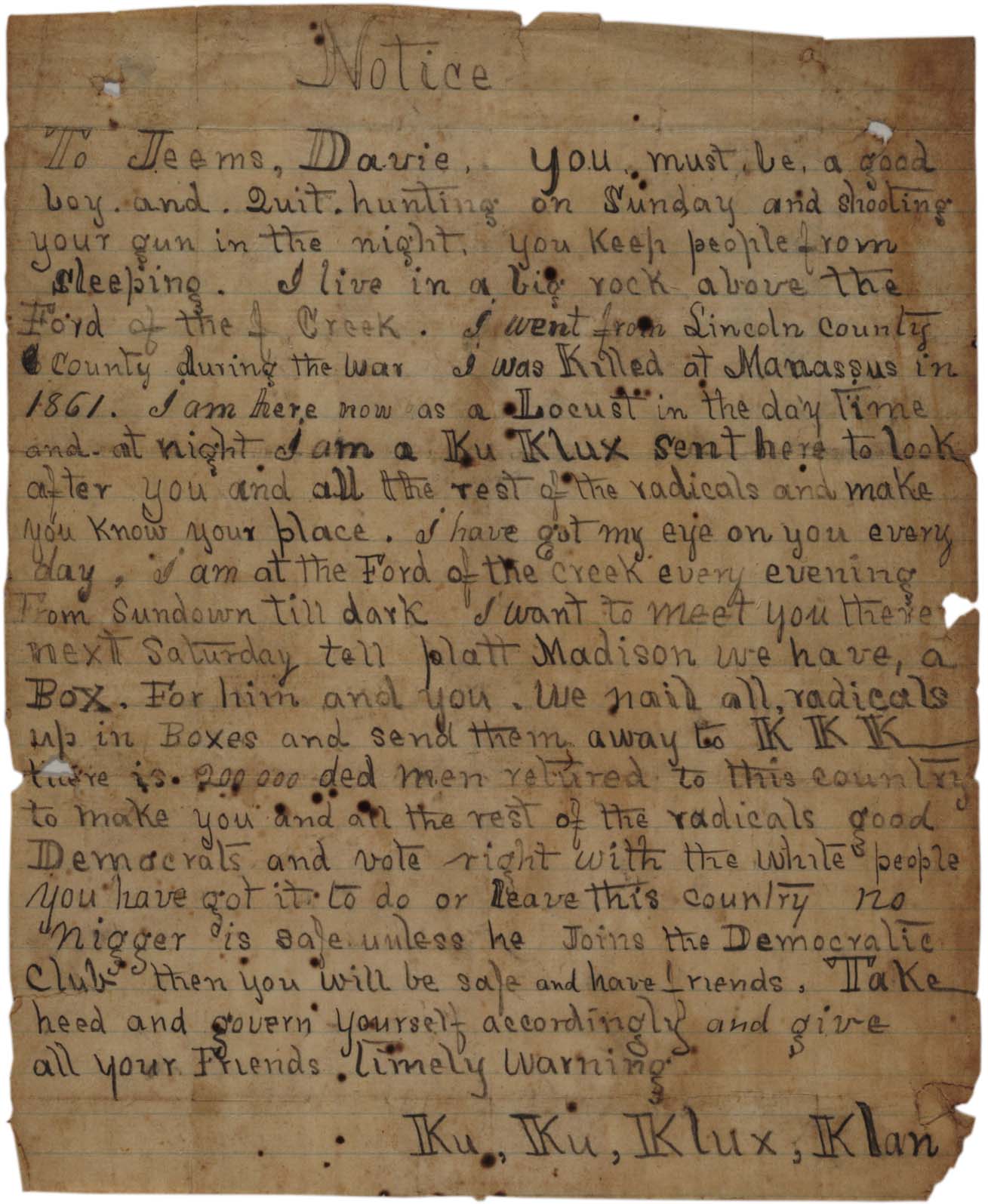

In this case, the target was Davie Jeems, a black Republican recently elected sheriff in Lincoln County, Georgia. The language of the document evokes a ghostly menacing presence; even the handwriting is reminiscent of a ransom note. The word "notice" and the two holes at the top indicate that it was most likely posted in a public place. Someone has written on the back of the sheet that "similar threats have prevented all the other Republican officers to take their [commissions]." With the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1871, the already weakened Klan became dormant, but it resurfaced again in 1915.

Notice

To Jeems, Davie. you. must. be, a good boy. and. Quit. hunting on Sunday and shooting your gun in the night. you keep people from sleeping. I live in a big rock above the Ford of the Creek. I went from Lincoln County County [sic] during the War I was Killed at Manassus in 1861. I am here now as a Locust in the day Time and. at night I am a Ku Klux sent here to look after you and all the rest of the radicals and make you know your place. I have got my eye on you every day, I am at the Ford of the creek every evening From Sundown till dark I want to meet you there next Saturday tell platt Madison we have, a Box. For him and you. We nail all, radicals up in Boxes and send them away to KKK - there is. 200 000 ded men retured to this country to make you and all the rest of the radicals good Democrats and vote right with the white people. A Ku Klux Klan threat, 1868 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Telegram from R. Starkweather, a teacher in Stevenson, Alabama, to General Crawford.Telegram from R. Starkweather, a teacher in Stevenson, Alabama, to General Crawford. :: Alabama Textual Materials Collection

In the message Starkweather asks for military assistance to protect the city from Klan violence: "Guard needed here--Civil guard overpowered and prisoner taken out by Ku Klux, our lives in danger--Officer in charge refused to stay." A transcription is included. Date 1870 March 1

Letter from Sheriff W. L. Guin in Vernon, Alabama, to Governor William Hugh Smith.

Letter from Sheriff W. L. Guin in Vernon, Alabama, to Governor William Hugh Smith. :: Alabama Textual Materials Collection

In the letter Guin, the sheriff of Sanford County (present-day Lamar County) describes violence against African American citizens in Fayette County. He gives details about six murders that have occurred in the last few months; the guilty parties have not been punished, even though some victims were carried away in "open daylight." He does not mention the Ku Klux Klan specifically, but he describes an incident that is characteristic of Klan activity: "There was a band of disguised men rode into Fayetteville after night during the last circuit court. They are also giving orders to whipping and abusing negros [sic] around Fayetteville, and threatening to chastise them if they appear when summoned to go to court." Though he knows of no similar "outrages" in his own area, he also refers to problems in Walker, Greene, Tuscaloosa, and Morgan Counties.

Black Militias sprouted up all over the south to protect Black families and Black people in general during Reconstruction -- due to the Union Army leaving the South -- and the newly freedman unprotected.

After the Civil War, southern states slowly began to rebuild their state militias. Among these new militia organizations were a limited number of black units, including three in Alabama: the Magic City Guards in Birmingham, Gilmer's Rifles in Mobile, and the Capital City Guards in Montgomery. Like their counterparts throughout the South, members of these militias endured neglect and persistent discrimination from state government and white military organizations. Members often suffered from the same racism found in their local communities. Despite the rise of Jim Crow laws, however, two of the three Alabama black militia units remained active into the late-nineteenth century (Gilmer's Rifles) and early-twentieth century (Capital City Guards), and their longevity owed much to the political skills and determination of their leaders, Reuben Romulus Mims of Mobile and Abraham Calvin Caffey of Montgomery.

Black Militias in Alabama | Encyclopedia of Alabama

South Carolina:

Hamburg, South Carolina, was an all-black town on the border with Georgia, an area that was a stronghold for the Democratic Party. Hearing news of white militias forming in surrounding towns, the intendant (or mayor) of Hamburg, John Gardner, formed an all-black militia of 84 men and, with the following letter, asked the governor to arm them as part of the state’s National Guard. Black South Carolinians Form a Militia For Protection (1874)

Jim Williams (c 1830 - March 6, 1871) was a civil rights leader and African-American militia leader in the 1860s and 1870s in York County, South Carolina. He escaped slavery during the US Civil War and joined the Union Army. After the war, Williams led a black militia organization which sought to protect black rights in the area. In 1871, he was lynched and hung by members of the local Ku Klux Klan. As a result, a large group of local blacks emigrated to Liberia.

UpAndComing

Veteran

Southern whites were very divided in 1867. Some of them said, "We've got to go out. We've got to mobilize ourselves. We've got to go out and out-vote these people." Most Southern states had white majorities. So even if all blacks voted, if the whites could unite against them, they could still keep control. In other places they said, "No, this is a travesty of democracy. We're just going to boycott. We're going to have nothing to do with it. Let them go ahead and they'll do all sorts of crazy things, and they'll discredit themselves." And then there were some white Southern leaders who said, "Well, we've got to go out and appeal to them. We've got to get them to vote for us. They don't have to vote Republican." And some of them actually went and gave speeches to black gatherings, and basically said, "Look, we were masters... You understand how good slavery was. You should vote for us." But those speeches didn't seem to get a lot of support. So there was a lot of uncertainty and political division within the white population in 1867, about how to respond to this completely new situation.From 1868 through the early 1870s the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) functioned as a loosely organized group of political and social terrorists. The Klan's goals included the political defeat of the Republican Party and the maintenance of absolute white supremacy in response to newly gained civil and political rights by southern blacks after the Civil War (1861-65). They were more successful in achieving their political goals than they were with their social goals during the Reconstruction era.

KKK formed because they did not want newly freedmen -- or Black people in general anywhere in the U.S. to have rights. They didn't want them to vote, be employed, go to school, run a business -- anything. In Reconstruction, the KKK served as a terrorism group to stop Black people from voting. Political terrorism.

In this case, the target was Davie Jeems, a black Republican recently elected sheriff in Lincoln County, Georgia. The language of the document evokes a ghostly menacing presence; even the handwriting is reminiscent of a ransom note. The word "notice" and the two holes at the top indicate that it was most likely posted in a public place. Someone has written on the back of the sheet that "similar threats have prevented all the other Republican officers to take their [commissions]." With the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1871, the already weakened Klan became dormant, but it resurfaced again in 1915.

Notice

To Jeems, Davie. you. must. be, a good boy. and. Quit. hunting on Sunday and shooting your gun in the night. you keep people from sleeping. I live in a big rock above the Ford of the Creek. I went from Lincoln County County [sic] during the War I was Killed at Manassus in 1861. I am here now as a Locust in the day Time and. at night I am a Ku Klux sent here to look after you and all the rest of the radicals and make you know your place. I have got my eye on you every day, I am at the Ford of the creek every evening From Sundown till dark I want to meet you there next Saturday tell platt Madison we have, a Box. For him and you. We nail all, radicals up in Boxes and send them away to KKK - there is. 200 000 ded men retured to this country to make you and all the rest of the radicals good Democrats and vote right with the white people. A Ku Klux Klan threat, 1868 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Telegram from R. Starkweather, a teacher in Stevenson, Alabama, to General Crawford.

Telegram from R. Starkweather, a teacher in Stevenson, Alabama, to General Crawford. :: Alabama Textual Materials Collection

In the message Starkweather asks for military assistance to protect the city from Klan violence: "Guard needed here--Civil guard overpowered and prisoner taken out by Ku Klux, our lives in danger--Officer in charge refused to stay." A transcription is included. Date 1870 March 1

Letter from Sheriff W. L. Guin in Vernon, Alabama, to Governor William Hugh Smith.

Letter from Sheriff W. L. Guin in Vernon, Alabama, to Governor William Hugh Smith. :: Alabama Textual Materials Collection

In the letter Guin, the sheriff of Sanford County (present-day Lamar County) describes violence against African American citizens in Fayette County. He gives details about six murders that have occurred in the last few months; the guilty parties have not been punished, even though some victims were carried away in "open daylight." He does not mention the Ku Klux Klan specifically, but he describes an incident that is characteristic of Klan activity: "There was a band of disguised men rode into Fayetteville after night during the last circuit court. They are also giving orders to whipping and abusing negros [sic] around Fayetteville, and threatening to chastise them if they appear when summoned to go to court." Though he knows of no similar "outrages" in his own area, he also refers to problems in Walker, Greene, Tuscaloosa, and Morgan Counties.

Black Militias sprouted up all over the south to protect Black families and Black people in general during Reconstruction -- due to the Union Army leaving the South -- and the newly freedman unprotected.

Alabama:

After the Civil War, southern states slowly began to rebuild their state militias. Among these new militia organizations were a limited number of black units, including three in Alabama: the Magic City Guards in Birmingham, Gilmer's Rifles in Mobile, and the Capital City Guards in Montgomery. Like their counterparts throughout the South, members of these militias endured neglect and persistent discrimination from state government and white military organizations. Members often suffered from the same racism found in their local communities. Despite the rise of Jim Crow laws, however, two of the three Alabama black militia units remained active into the late-nineteenth century (Gilmer's Rifles) and early-twentieth century (Capital City Guards), and their longevity owed much to the political skills and determination of their leaders, Reuben Romulus Mims of Mobile and Abraham Calvin Caffey of Montgomery.

Black Militias in Alabama | Encyclopedia of Alabama

South Carolina:

Hamburg, South Carolina, was an all-black town on the border with Georgia, an area that was a stronghold for the Democratic Party. Hearing news of white militias forming in surrounding towns, the intendant (or mayor) of Hamburg, John Gardner, formed an all-black militia of 84 men and, with the following letter, asked the governor to arm them as part of the state’s National Guard. Black South Carolinians Form a Militia For Protection (1874)

Jim Williams (c 1830 - March 6, 1871) was a civil rights leader and African-American militia leader in the 1860s and 1870s in York County, South Carolina. He escaped slavery during the US Civil War and joined the Union Army. After the war, Williams led a black militia organization which sought to protect black rights in the area. In 1871, he was lynched and hung by members of the local Ku Klux Klan. As a result, a large group of local blacks emigrated to Liberia.

Great info

Ol’Otis

The Picasso of the Ghetto

i though this was known already