How Anti-Imperialism Became a Justification for Terror

www.zinebriboua.com

The Bataclan Massacre, the Post-1968 Left, and the Unwelcome Victim

Summarize

How Anti-Imperialism Became a Justification for Terror

Zineb Riboua

Bataclan Survivor Shocked to Find Surgeon Selling NFT of Her X-Rayed Bullet Wound - Business Insider

“They say that Death embellishes its victims and exaggerates their virtues, but in general it is actually life that wronged them.”

Marcel Proust, Pleasures and Days

The Unwelcome Victim

I was a student at the time. The Bataclan massacre—which killed 132 people—came only 10 months after the attack on Charlie Hebdo. Like everyone else, I was shocked and speechless. But my disbelief had less to do with what had happened than with what I heard in the aftermath.

In class, among professors, and across that familiar ecosystem of activists, media performers, and ideological hobbyists, a disturbing refrain emerged:

“The French deserved it.”

“This is the price of France’s crimes.”

It was grotesque, an acrobatic form of moral inversion. As families mourned their dead, the professionals of outrage were already at work, producing theories to absolve the killers and indict the country. Some insisted that France had “created” the Islamic State, others admitted the claim was false but insisted it didn’t matter because the attack was, in their view, deserved.

I remember sitting quietly during these discussions, watching one classmate in particular. He stood up and declared he felt “little remorse” for the victims. But, what struck me most was that he wasn’t alone. In his mind, and in the minds of many, the victims were no longer victims at all. They had become symbols, “necessary sacrifices,” proof that a terrorist organization openly calling for horror and the destruction of Europe and the West could strike its enemies with righteous force.

What the world no longer remembers, and what many never noticed at all, perhaps because these debates largely took place within the Francophone sphere, is the atmosphere that surrounded those attacks. The justifications, the rationalizations, the strange confidence of people who had nothing at stake and who nonetheless allowed themselves to speak as if they were the moral judges of the dead.

There was an audacity that still unsettles me. The audacity to look a mourning father in the eye and tell him that he was not the victim. To explain that his son or daughter was nothing more than an unfortunate casualty of history, a small figure swept away by a struggle that, according to this decolonial ideology, demanded its offerings. Some went even further. They suggested he might find a kind of consolation, that he might even welcome the idea that these so-called miscreants had been killed, or that music was forbidden anyway.

These remarks were not marginal. They moved through classrooms, student associations, activist circles, and media spaces that presented themselves as guardians of seriousness. They revealed something disturbing, a readiness to invert victimhood so completely that grief itself became suspect, something to be explained away, corrected, redirected toward the sanctioned narrative.

The Post-1968 Left

What I think matters is that these ideas did not emerge in a vacuum.

They were cultivated over decades, nourished by a long intellectual tradition that gave them prestige. The reversal of victim and oppressor, the instinct to interpret violence “from below” as almost sacred, took shape long before the Bataclan. Its decisive moment was the intellectual upheaval of May 1968 in Paris.

What happened in 1968 in France was the moment when an entire intellectual class decided that France itself, and more broadly the West, was the source of all the world’s injustices. May ‘68 began with student unrest, but it became something much larger. Universities were occupied, factories shut down, and over a million workers went on strike, every institution appeared suddenly fragile, every form of authority ripe for overturning.

The French intellectuals of that era did not stay on the margins observing events. They entered the movement and allowed the movement to redefine their mission. They walked into the streets, wrote in the newspapers, spoke in the occupied amphitheaters, and declared that France was living through its great reckoning. They believed they were witnessing the final unmasking of bourgeois hypocrisy, the long-awaited judgment on France’s colonial past, and its complicity with capitalism.

May 1968: A Month of Revolution Pushed France Into the Modern World - The New York Times

Writers and philosophers who had built their reputations on critique suddenly found themselves intoxicated by the spectacle of revolt. Simone de Beauvoir spoke of the movement as a renewal of life. Jacques Derrida, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Alain Geismar, and others transformed the atmosphere by insisting that France must confront its guilt.

Régis Debray, freshly released from a Bolivian prison, added a romantic vision of the guerrillero. The figure of Che Guevara was everywhere, as a martyr of anti-imperial justice. Philippe Sollers and the Tel Quel group embraced Maoism with a fervor that bordered on devotion. In their minds, China was the new horizon of moral clarity, a revolutionary purity that stood in contrast to the decadence of the West.

Mai 68

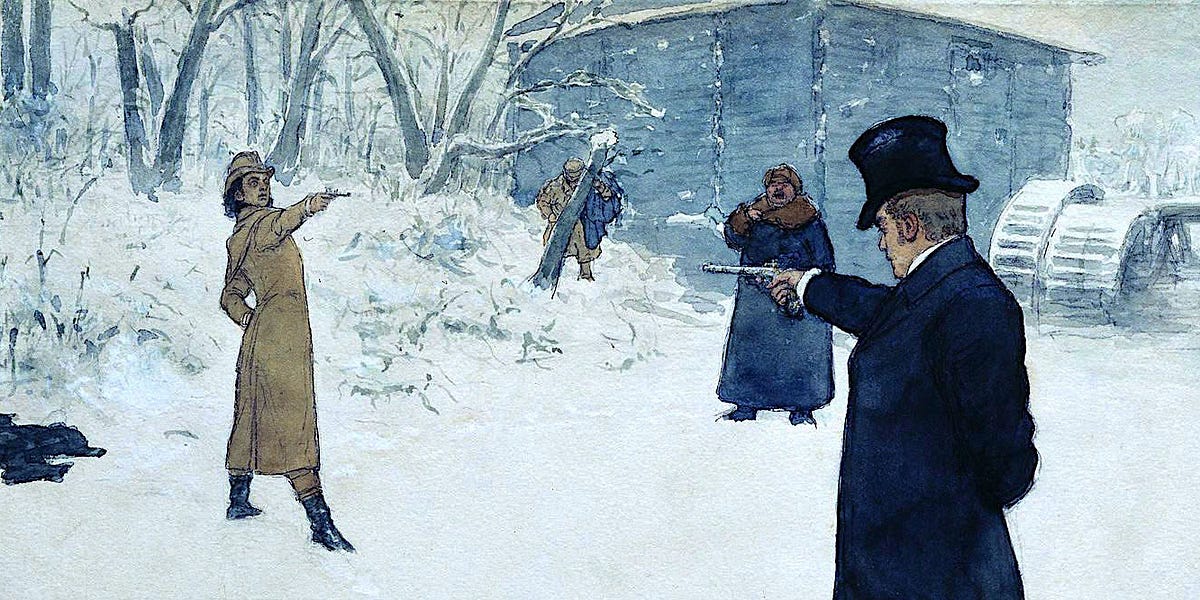

Che Guevara and Fidel Castro posters were plastered across the walls of the Sorbonne in Paris during the student protests of May ’68.

The intellectuals of the time rewrote the narrative of the twentieth century. Every ill in the world could be traced back to imperialism, capitalism, or the legacy of Western domination. The idea took root that violence and horror carried out by the oppressed possessed a kind of privileged truth. It could be tragic, even brutal, however, it was believed to reveal the world more honestly than any institution, argument, or moral norm. Over time, this conviction seeped into universities and shaped entire generations of students, who were encouraged to see rebellion, and at its extreme, terrorism directed against the West, as the most authentic expression of political reality.

This is why the reaction to the Bataclan did not emerge from nowhere. When some voices claimed that France had brought violence upon itself, they were echoing a long inheritance. Victims of terrorism were no longer seen as human beings but as symbols within an old romantic vision of revolt. The perpetrators were recast as the oppressed, and the victims as the guilty. The reflex that once treated every uprising abroad as anti-imperialist justice now treats violence inside France as history delivering its verdict.

Making the Jihadi a Victim

Islam, for many intellectuals, eventually entered this structure not as a religion but as a sign, a symbol, a flag. It became the symbol of the excluded and the humiliated, the permanent “post-colonial subject.”

Even when the actors were jihadist movements with imperial ambitions of their own, the narrative remained the same. The violence was quietly redirected into the memory of Algeria, or the ghosts of Indochina, or the idea that colonial history continues in new forms. The Islamic State proclaimed a universal caliphate, killed Muslims and non-Muslims alike, destroyed entire communities, and openly declared its intention to murder Western civilians. But in certain French circles, the event was filtered through the old opposition between oppression and resistance. And beneath that filter lay a second layer: anything resembling a patriotic reaction or any instinct to defend France was immediately coded as suspect.

This is what created the confusion after the Bataclan. The clarity of the massacre was total. Young people were killed in a concert hall. A crime so direct it should have left no room for interpretation, but the reflex to do so survived. Some looked at the dead and did not see individuals, they saw representatives of a civilization they believed guilty. They saw symbols of a historical imbalance.

To say that France had suffered, to affirm the innocence of the victims, to defend the nation in that moment, would have required affirming something like patriotism. And patriotism, in the mental universe of the post-68 Left, is nearly impossible to express without suspicion. The result was a sort of Kafkaesque paralysis.

This confusion comes directly from the inheritance of 1968. The Left that emerged from that period trained itself to read every conflict as the aftershock of colonialism. Once Islam became associated with the descendants of former colonial powers, the old categories merged. The jihadist became the post-colonial rebel. The terrorist act became a form of revenge against history. The victim became the embodiment of France, and France became the embodiment of its crimes. And because patriotism had been morally delegitimized, defending the victims as French became unacceptable, suspicious, weird, unsettling.

More importantly, a segment of the French intelligentsia recast Islam as political symbolism rather than a religious world. Jihadist violence was interpreted as a political expression, not cruelty. This came not from engagement with Islamic history but from the need to preserve an ideological narrative of oppression and resistance. In the process, Islam was reduced to a surface for post-1968 projections. This same distortion led many to misread the Islamic State. ISIS was not the voice of the marginalized but an imperial project seeking to overthrow Middle Eastern states, yet this reality was obscured by the insistence on placing it within an old anti-imperialist story.

Once this shift occurred, even a massacre like the Bataclan could be folded back into the older narrative. The victims faded because they did not fit the script. Any impulse to defend the country, to mourn collectively, or to describe the attack plainly risked being dismissed as nationalism. Reality bent to protect the framework, and in that distortion the final inversion appeared: the killers were treated as bearers of history, and the dead as bearers of France. Public grief itself became uncomfortable, and in that discomfort, the victims were abandoned twice.

The United States is not France, but it is beginning to develop a similar reflex. These ideas never appear out of thin air, and their presence is not inherently harmful. I still read Foucault, and I still enjoy Derrida’s writings on painting and art. Engaging difficult and unsettling thinkers is part of a healthy intellectual life. A democracy depends on argument and disagreement. The problem arises when interpretation begins to blur essential distinctions and is treated as an ultimate truth (even though they insist that there is no objective truth, only their own), particularly in moments of danger.

Jihadist movements are still active, foreign adversaries test American resolve, and political violence is no longer an abstraction. In such a landscape, hesitation about affirming national cohesion carries real consequences. Patriotism becomes something to be softened or hidden, as if expressing a shared civic identity risks being mistaken for partisanship. That hesitation obscures judgment at precisely the moment judgment is needed, whether jihadist groups or foreign proxies target Americans.

France struggled to speak with one voice after a terror attack because the idea of national solidarity had long been treated with suspicion. The United States is not there, but something similar is forming. The challenge is not the existence of dissent or criticism, both of which are essential, but the growing reluctance to affirm the bare civic ground on which a society recognizes danger. In an era of multiplying threats, that reluctance is not merely a cultural debate, it is fundamentally a strategic vulnerability.