AFRICOM’s Base Bonanza

When AFRICOM became an independent command in 2008, Camp Lemonnier was reportedly still one of the few American outposts on the continent. In the years since, the U.S. has embarked on nothing short of a building boom -- even if the command is loath to refer to it in those terms. As a result, it’s now able to carry out increasing numbers of overt and covert missions, from training exercises to drone assassinations.

“AFRICOM, as a new command, is basically a laboratory for a different kind of warfare and a different way of posturing forces,” says Richard Reeve, the director of the

Sustainable Security Programme at the

Oxford Research Group, a London-based think tank. “Apart from Djibouti, there’s no significant stockpiling of troops, equipment, or even aircraft. There are a myriad of ‘lily pads’ or small forward operating bases... so you can spread out even a small number of forces over a very large area and concentrate those forces quite quickly when necessary.”

Indeed, U.S. staging areas, cooperative security locations, forward operating locations (FOLs), and other outposts -- many of them involved in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance activities and Special Operations missions -- have been built (or built up) in

Burkina Faso,

Cameroon, the

Central African Republic,

Chad,

Djibouti,

Ethiopia,

Gabon,

Ghana,

Kenya,

Mali,

Niger,

Senegal,

the Seychelles,

Somalia,

South Sudan, and

Uganda. A 2011 report by Lauren Ploch

, an analyst in African affairs with the Congressional Research Service, also mentioned U.S. military access to locations in Algeria, Botswana, Namibia, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone, Tunisia, and Zambia. AFRICOM failed to respond to scores of requests by this reporter for further information about its outposts and related matters, but an analysis of open source information, documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, and other records show a persistent, enduring, and growing U.S. presence on the continent.

“A cooperative security location is just a small location where we can come in... It would be what you would call a very austere location with a couple of warehouses that has things like: tents, water, and things like that,” explained AFRICOM’s Rodriguez. As he implies, the military doesn’t consider CSLs to be “bases,” but whatever they might be called, they are more than merely a few tents and cases of bottled water.

Designed to accommodate about 200 personnel, with runways suitable for C-130 transport aircraft, the sites are primed for conversion from temporary, bare-bones facilities into something more enduring. At least three of them in Senegal, Ghana, and Gabon are apparently designed to facilitate faster deployment for a rapid reaction unit with a mouthful of a moniker: Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Crisis Response-Africa (

SPMAGTF-CR-AF). Its forces are

based in

Morón, Spain, and Sigonella, Italy, but are focused on Africa. They rely heavily on MV-22 Ospreys,

tilt-rotor aircraft that can take-off, land, and hover like helicopters, but fly with the speed and fuel efficiency of a turboprop plane.

This combination of manpower, access, and technology has come to be known in the military by the moniker “

New Normal.”

Birthed in the wake of the September 2012 attack in Benghazi, Libya, that killed U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans, the New Normal effectively allows the U.S. military quick access 400 miles inland from any CSL or, as Richard Reeve notes, gives it “a reach that extends to just about every country in West and Central Africa.”

The concept was

field-tested as South Sudan plunged into civil war and 160 Marines and sailors from Morón were forward deployed to Djibouti in late 2013. Within hours, a contingent from that force was sent to Uganda and, in early 2014, in conjunction with another rapid reaction unit, dispatched to South Sudan to evacuate 20 people from the American embassy in Juba. Earlier this year, SPMAGTF-CR-AF ran trials at its African staging areas including the CSL in Libreville, Gabon, deploying nearly 200 Marines and sailors along with four Ospreys, two C-130s, and more than 150,000 pounds of materiel.

A similar test run was carried out at the Senegal CSL located at Dakar-Ouakam Air Base, which can also host 200 Marines and the support personnel necessary to sustain and transport them. “What the CSL offers is the ability to forward-stage our forces to respond to any type of crisis,” Lorenzo Armijo, an operations officer with SPMAGTF-CR-AF, told a military reporter. “That crisis can range in the scope of military operations from embassy reinforcement to providing humanitarian assistance.”

Another CSL, mentioned in a July 2012 briefing by U.S. Army Africa, is located in

Entebbe, Uganda. From there, according to a

Washington Postinvestigation, U.S. contractors have flown surveillance missions using innocuous-looking turboprop airplanes. “The AFRICOM strategy is to have a very light touch, a light footprint, but nevertheless facilitate special forces operations or ISR [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance] detachments over a very wide area,” Reeve says. “To do that they don’t need very much basing infrastructure, they need an agreement to use a location, basic facilities on the ground, a stockpile of fuel, but they also can rely on private contractors to maintain a number of facilities so there aren’t U.S. troops on the ground.”

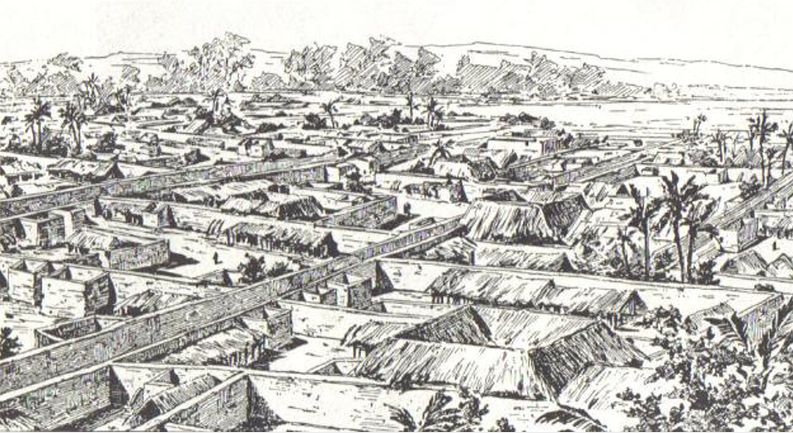

Click here to see a larger version

U.S. Army Africa briefing slide from 2012 detailing work at the Entebbe CSL

The Outpost Archipelago

AFRICOM ignored my requests for further information on CSLs and for the designations of other outposts on the continent, but

according to a 2014 article in

Army Sustainment on “Overcoming Logistics Challenges in East Africa,” there are also “at least nine forward operating locations, or FOLs.” A 2007 Defense Department news release referred to an FOL in Charichcho, Ethiopia. The U.S. military also utilizes “Forward Operating Location Kasenyi” in Kampala, Uganda. A 2010 report by the Government Accountability Office

mentioned forward operating locations in Isiolo and Manda Bay, both in Kenya.

Camp Simba in Manda Bay has, in fact, seen significant expansion in recent years. In 2013, Navy Seabees, for example,

worked 24-hour shifts to extend its runway to enable larger

aircraft like C-130s to land there, while other projects were initiated to accommodate greater numbers of troops in the future, including increased fuel and potable water storage, and more latrines. The base serves as a home away from home for Navy personnel and Army Green Berets among other U.S. troops and, as recently

revealed at the

Intercept, plays an integral role in the secret

drone assassination program aimed at militants in neighboring Somalia as well as in Yemen.

Drones have played an increasingly large role in this post-9/11 build-up in Africa. MQ-1 Predators have, for instance, been based in Chad’s capital,

N’Djamena, while their newer, larger, more far-ranging cousins,

MQ-9 Reapers, have been

flown out of Seychelles International Airport. As of June 2012,

according to the

Intercept, two contractor-operated drones, one Predator and one Reaper, were based in

Arba Minch, Ethiopia, while a detachment with one

Scan Eagle (a low-cost drone used by the Navy) and a remotely piloted helicopter known as an

MQ-8 Fire Scout operated off the coast of East Africa. The U.S. also recently began setting up a

base in Cameroon for unarmed Predators to be used in the battle against Boko Haram militants.

Click here to see a larger version

U.S. Army Africa briefing slide from 2013 obtained by TomDispatch

via the Freedom of Information Act