You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The El Chapo Trial is nuts; $100m Bribe to NIETO?! UPDATE: FOUND GUILTY ON ALL COUNTS

- Thread starter ☑︎#VoteDemocrat

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?news.vice.com

Who ordered the murder of a legendary Mexican journalist? El Chapo's trial only adds to the mystery

8-10 minutes

Listen to "Chapo: Kingpin on Trial" for free, exclusively on Spotify.

Episode 7 deals directly with Javier's death, its impact, and its connection to El Chapo. Listen to that episode here.

BROOKLYN, New York — In the months after Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán was extradited from Mexico to New York to stand trial as the leader of the Sinaloa cartel, the city of Culiacán descended into chaos. Allies turned against each other, fighting to fill the power vacuum.

El Chapo’s sons — known as Los Chapitos — were on one side. His former right-hand man, Dámaso López Nuñez, was on the other. And a journalist, Javier Valdez Cárdenas, was caught in the middle. While Los Chapitos and López battled for the throne, Valdez chronicled their power struggle in the pages of RioDoce. He was the cofounder of the weekly newspaper and wrote a column, Malayerba, which he used to elucidate the opaque world of organized crime.

At around 12 p.m. on May 15, 2017, Valdez was gunned down in the street moments after leaving his office. Violence against journalists is all too common in Mexico — at least 10 were killed in 2018 — but Valdez’s death sparked exceptional outrage because he was no ordinary reporter. He was a beloved figure, the author of several books, and the winner of The Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award. Many murders of journalists go unsolved in Mexico, but Valdez’s case prompted calls to end the impunity and swiftly bring his killers to justice.

On Wednesday, during Chapo’s trial in Brooklyn, López was forced for the first time to respond to the allegation that he and his son were responsible for Valdez’s death. The question came from El Chapo’s lawyer, Eduardo Balarezo, while López was under cross-examination. He vehemently denied responsibility, and instead cast blame on Los Chapitos.

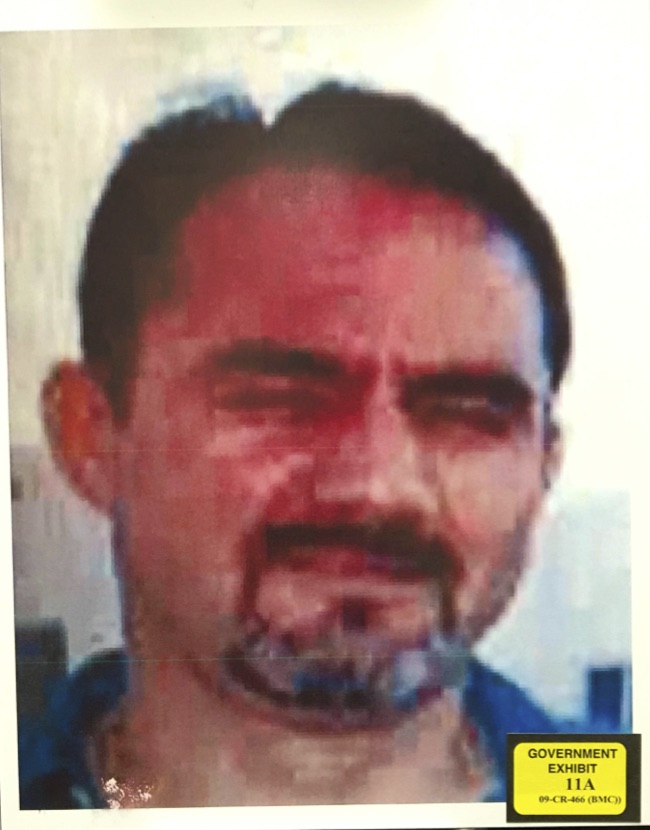

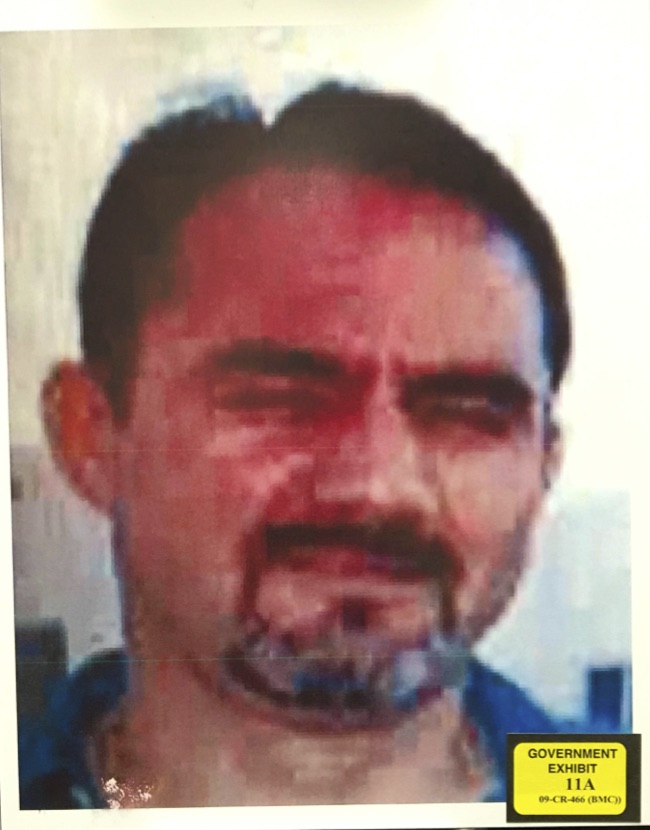

Dámaso López. (Photo via U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of New York)

“My son and I are innocent of this man’s murder,” López testified. “I’m telling the truth. I’ve sworn to tell the truth and I’m abiding by my oath.”

Valdez’s stories shortly before his death included an interview with López, known as Lic or Licenciado, and a subsequent column that was critical of López’s son, El Mini Lic. But at first the primary suspects in Valdez’s murder were El Chapo’s sons, Iván and Alfredo. They had reached out to Valdez through an intermediary and asked him not to publish the interview with López. When he went through with it anyway, Los Chapitos sent gunmen to collect every copy of the newspaper before it could be distributed in Culiacán.

López told his version of this story on the witness stand. He testified that he gave his interview with Valdez to set the record straight about an inaccurate story published by another newspaper in Mexico. According to López, Chapo’s sons gave the green light for Valdez to be executed because he was willing to publish the truth.

“He was a very good journalist,” López said of Valdez. “He was ethical and he did publish it. He disobeyed the orders of my compadre’s sons and that’s why he was killed. And since my compadre's sons are in collusion with the government, they did not find a culprit and blamed my son.”

Indeed, López’s son Mini Lic, whose real name is Dámaso López Serrano, was ultimately identified as having ordered the hit on Valdez. The motive was thought to be revenge for a public insult. In his column, Valdez called Mini Lic a “weekend gunman,” among other barbs. López claimed during his testimony that Chapo’s sons had forced Valdez and RioDoce to publish the column.

A memorial for Javier Valdez at the scene of his murder near the RioDoce offices in Culiacán. (Photo by Keegan Hamilton.)

Two of the suspected gunmen in Javier’s murder, who go by the names El Koala and El Quilo, are in Mexican custody on homicide charges. A third, El Diablo, was killed in the Mexican state of Sonora in September 2017.

López, 52, was arrested in Mexico City in May 2017. He was in prison when Valdez was killed, but according to reports from Mexican newspapers, including RioDoce, the gunman El Koala belonged to his faction of the Sinaloa cartel. El Koala’s payment for the killing was said to be a pistol bearing the emblem of López’s faction.

López was extradited to the U.S. last July and sentenced to life in prison after pleading guilty to federal drug conspiracy charges. He testified against Chapo in hopes of receiving a reduced sentence. López was asked Thursday by Balarezo whether he was familiar with El Koala and El Kilo. Prosecutors objected to the question and called for a private sidebar conversation with the judge to discussion the issue. Afterward, Balarezo moved on and López was never allowed to respond.

López admitted Wednesday to having hundreds of sicarios and pistoleros at his disposal during his war with Los Chapitos. Balarezo showed the jury a patch — with crossed rifles, a rooster, and a skull — that belonged to the FED, or Fuerzas Especiales de Dámaso, López’s personal special forces unit.

A patch worn by gunmen from the FED. (Photo courtesy of Eduardo Balarezo)

Mini Lic surrendered to U.S. authorities at a border crossing in Calexico, California, on July 27, 2017, and pleaded guilty last January to drug conspiracy charges. López testified that his son was forced to flee Mexico because of the war with Chapo’s sons. Mini Lic has never publicly addressed the allegation that he put out the hit on Valdez.

For me, the killing was personal. Valdez had helped me report on two stories in Sinaloa prior to his death, and his murder was covered in our podcast “Chapo: Kingpin on Trial.” In episode 7 of the show, RioDoce reporter Miguel Angel Vega and I discuss the violence in Sinaloa after Chapo’s extradition and how it led to his colleague’s assassination. After López testified Wednesday, I called my co-host to get his response.

“I’m not really sure what to believe anymore,” Vega said. “If I could speak to Dámaso, I would ask something like, Did the people that killed Javier — they are identified, we know who they are — did they work for your faction of the cartel? Did they work for you or Mini Lic? And if they did, how do you explain that?’”

Vega was adamant that Valdez and RioDoce would not publish a story on the orders of Los Chapitos — or any other cartel members — as López alleged during his testimony. The newspaper, he said, practices “pure journalism.” Valdez, he added, knew there was an implicit threat when El Chapo’s sons asked him not to publish the interview with Licenciado, but he did it anyway because it was a story that needed to be told.

Vega noted that so-called “narco juniors” like Los Chapitos and Mini Lic have escalated the violence in Mexico, which was worse last year than ever before, with a record 28,816 homicides across the country. This year is off to an equally grim start, and already one journalist, 34-year-old Rafael Murúa Manríquez, has been murdered.

“The sons are not like all the other leaders, like Mayo, Chapo,” Vega said. “Those guys are old school and they give respect. This new generation is more violent. They’ve been rich since the very beginning. They are used to people coming to them to ask favors. They feel like gods. Whenever someone refuses them, they kill them.”

Jan-Albert Hootsen, the CPJ representative in Mexico, said his organization is closely monitoring El Chapo’s trial “to see whether any information comes to light that may be relevant to Javier’s case or that of any other murdered journalist.”

“Although several arrests have been made in Javier Valdez’s murder case, there are still lingering questions about who has given the order to carry out the murder,” Hootsen said. “As long as those questions remain unanswered, there is no full justice in the case.”

On Thursday, Mexican President Andres Manuel López Obrador said he will ask the government agency in charge of human rights to present a report about the progress in the investigation of Valdez’s murder and the unsolved killings of other journalists. He promised to find and punish “the material and intellectual authors" of Valdez’s assassination.

While there was some solace in López finally being confronted about the role he and his son allegedly played in Valdez’s murder, Vega said he and others, and RioDoce, will not rest until the case has been solved once and for all.

“There’s this whisper for justice that’s still out in the air,” Vega said. “Javier’s wife, she’s still screaming for justice. It doesn’t matter if it’s Lic or Mini Lic, there’s still no justice.”

Cover: Javier Valdez on the cover of RioDoce after his murder. (Photo by Keegan Hamilton.)

Cave Savage

Feminist

news.vice.com

Who ordered the murder of a legendary Mexican journalist? El Chapo's trial only adds to the mystery

8-10 minutes

Listen to "Chapo: Kingpin on Trial" for free, exclusively on Spotify.

Episode 7 deals directly with Javier's death, its impact, and its connection to El Chapo. Listen to that episode here.

BROOKLYN, New York — In the months after Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán was extradited from Mexico to New York to stand trial as the leader of the Sinaloa cartel, the city of Culiacán descended into chaos. Allies turned against each other, fighting to fill the power vacuum.

El Chapo’s sons — known as Los Chapitos — were on one side. His former right-hand man, Dámaso López Nuñez, was on the other. And a journalist, Javier Valdez Cárdenas, was caught in the middle. While Los Chapitos and López battled for the throne, Valdez chronicled their power struggle in the pages of RioDoce. He was the cofounder of the weekly newspaper and wrote a column, Malayerba, which he used to elucidate the opaque world of organized crime.

At around 12 p.m. on May 15, 2017, Valdez was gunned down in the street moments after leaving his office. Violence against journalists is all too common in Mexico — at least 10 were killed in 2018 — but Valdez’s death sparked exceptional outrage because he was no ordinary reporter. He was a beloved figure, the author of several books, and the winner of The Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award. Many murders of journalists go unsolved in Mexico, but Valdez’s case prompted calls to end the impunity and swiftly bring his killers to justice.

On Wednesday, during Chapo’s trial in Brooklyn, López was forced for the first time to respond to the allegation that he and his son were responsible for Valdez’s death. The question came from El Chapo’s lawyer, Eduardo Balarezo, while López was under cross-examination. He vehemently denied responsibility, and instead cast blame on Los Chapitos.

Dámaso López. (Photo via U.S. Attorney's Office for the Eastern District of New York)

“My son and I are innocent of this man’s murder,” López testified. “I’m telling the truth. I’ve sworn to tell the truth and I’m abiding by my oath.”

Valdez’s stories shortly before his death included an interview with López, known as Lic or Licenciado, and a subsequent column that was critical of López’s son, El Mini Lic. But at first the primary suspects in Valdez’s murder were El Chapo’s sons, Iván and Alfredo. They had reached out to Valdez through an intermediary and asked him not to publish the interview with López. When he went through with it anyway, Los Chapitos sent gunmen to collect every copy of the newspaper before it could be distributed in Culiacán.

López told his version of this story on the witness stand. He testified that he gave his interview with Valdez to set the record straight about an inaccurate story published by another newspaper in Mexico. According to López, Chapo’s sons gave the green light for Valdez to be executed because he was willing to publish the truth.

“He was a very good journalist,” López said of Valdez. “He was ethical and he did publish it. He disobeyed the orders of my compadre’s sons and that’s why he was killed. And since my compadre's sons are in collusion with the government, they did not find a culprit and blamed my son.”

Indeed, López’s son Mini Lic, whose real name is Dámaso López Serrano, was ultimately identified as having ordered the hit on Valdez. The motive was thought to be revenge for a public insult. In his column, Valdez called Mini Lic a “weekend gunman,” among other barbs. López claimed during his testimony that Chapo’s sons had forced Valdez and RioDoce to publish the column.

A memorial for Javier Valdez at the scene of his murder near the RioDoce offices in Culiacán. (Photo by Keegan Hamilton.)

Two of the suspected gunmen in Javier’s murder, who go by the names El Koala and El Quilo, are in Mexican custody on homicide charges. A third, El Diablo, was killed in the Mexican state of Sonora in September 2017.

López, 52, was arrested in Mexico City in May 2017. He was in prison when Valdez was killed, but according to reports from Mexican newspapers, including RioDoce, the gunman El Koala belonged to his faction of the Sinaloa cartel. El Koala’s payment for the killing was said to be a pistol bearing the emblem of López’s faction.

López was extradited to the U.S. last July and sentenced to life in prison after pleading guilty to federal drug conspiracy charges. He testified against Chapo in hopes of receiving a reduced sentence. López was asked Thursday by Balarezo whether he was familiar with El Koala and El Kilo. Prosecutors objected to the question and called for a private sidebar conversation with the judge to discussion the issue. Afterward, Balarezo moved on and López was never allowed to respond.

López admitted Wednesday to having hundreds of sicarios and pistoleros at his disposal during his war with Los Chapitos. Balarezo showed the jury a patch — with crossed rifles, a rooster, and a skull — that belonged to the FED, or Fuerzas Especiales de Dámaso, López’s personal special forces unit.

A patch worn by gunmen from the FED. (Photo courtesy of Eduardo Balarezo)

Mini Lic surrendered to U.S. authorities at a border crossing in Calexico, California, on July 27, 2017, and pleaded guilty last January to drug conspiracy charges. López testified that his son was forced to flee Mexico because of the war with Chapo’s sons. Mini Lic has never publicly addressed the allegation that he put out the hit on Valdez.

For me, the killing was personal. Valdez had helped me report on two stories in Sinaloa prior to his death, and his murder was covered in our podcast “Chapo: Kingpin on Trial.” In episode 7 of the show, RioDoce reporter Miguel Angel Vega and I discuss the violence in Sinaloa after Chapo’s extradition and how it led to his colleague’s assassination. After López testified Wednesday, I called my co-host to get his response.

“I’m not really sure what to believe anymore,” Vega said. “If I could speak to Dámaso, I would ask something like, Did the people that killed Javier — they are identified, we know who they are — did they work for your faction of the cartel? Did they work for you or Mini Lic? And if they did, how do you explain that?’”

Vega was adamant that Valdez and RioDoce would not publish a story on the orders of Los Chapitos — or any other cartel members — as López alleged during his testimony. The newspaper, he said, practices “pure journalism.” Valdez, he added, knew there was an implicit threat when El Chapo’s sons asked him not to publish the interview with Licenciado, but he did it anyway because it was a story that needed to be told.

Vega noted that so-called “narco juniors” like Los Chapitos and Mini Lic have escalated the violence in Mexico, which was worse last year than ever before, with a record 28,816 homicides across the country. This year is off to an equally grim start, and already one journalist, 34-year-old Rafael Murúa Manríquez, has been murdered.

“The sons are not like all the other leaders, like Mayo, Chapo,” Vega said. “Those guys are old school and they give respect. This new generation is more violent. They’ve been rich since the very beginning. They are used to people coming to them to ask favors. They feel like gods. Whenever someone refuses them, they kill them.”

Jan-Albert Hootsen, the CPJ representative in Mexico, said his organization is closely monitoring El Chapo’s trial “to see whether any information comes to light that may be relevant to Javier’s case or that of any other murdered journalist.”

“Although several arrests have been made in Javier Valdez’s murder case, there are still lingering questions about who has given the order to carry out the murder,” Hootsen said. “As long as those questions remain unanswered, there is no full justice in the case.”

On Thursday, Mexican President Andres Manuel López Obrador said he will ask the government agency in charge of human rights to present a report about the progress in the investigation of Valdez’s murder and the unsolved killings of other journalists. He promised to find and punish “the material and intellectual authors" of Valdez’s assassination.

While there was some solace in López finally being confronted about the role he and his son allegedly played in Valdez’s murder, Vega said he and others, and RioDoce, will not rest until the case has been solved once and for all.

“There’s this whisper for justice that’s still out in the air,” Vega said. “Javier’s wife, she’s still screaming for justice. It doesn’t matter if it’s Lic or Mini Lic, there’s still no justice.”

Cover: Javier Valdez on the cover of RioDoce after his murder. (Photo by Keegan Hamilton.)

So El Chapo is snitching?

El Chapo Trial: A Cartel Killer Recalls the Kingpin’s Bloodthirsty Side

nytimes.com

El Chapo Trial: A Cartel Killer Recalls the Kingpin’s Bloodthirsty Side

6-8 minutes

Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known as El Chapo, was portrayed as a ruthless killer on Thursday by one of his former assassins. Here, a news crew outside the court last week.CreditKevin Hagen/Associated Press

Image

Joaquín Guzmán Loera, known as El Chapo, was portrayed as a ruthless killer on Thursday by one of his former assassins. Here, a news crew outside the court last week.CreditCreditKevin Hagen/Associated Press

A huge bonfire was burning at Joaquín Guzmán Loera’s mountain hide-out one night when the crime lord’s bodyguards brought him two enemy soldiers slumped across the backs of two A.T.V.s. The men — members of the Zetas, a rival cartel — had been tortured for hours and many of their bones had already been broken. The soldiers, as listless as “rag dolls,” according to a gunman who was there, could barely move.

In the glow of the firelight, Mr. Guzmán ordered the Zetas to be placed beside the flames and then approached them with a rifle. Pressing its barrel to the first man’s head, the kingpin cursed the soldier’s mother and abruptly pulled the trigger. After he had done the same to the second, he ordered his assassins to dispose of the bodies.

“Put them in the bonfire,” the gunman recalled Mr. Guzmán saying. “I don’t want any bones to remain.”

This morbid story was recounted on Thursday by Isaias Valdez Rios, a former cartel killer, at Mr. Guzmán’s drug trial in New York. Though dozens of murders have been described in court since the trial began 10 weeks ago, Judge Brian M. Cogan has sought to keep a tight leash on the gore. But Mr. Valdez’s testimony was exceptionally gruesome and marked the first time that jurors heard explicitly graphic examples of the bloodshed that Mexican cartels have long been known for. It was also the first time that evidence was shown that depicted the violence personally committed by the defendant, known to the world as El Chapo.

In three grueling hours on the witness stand, Mr. Valdez spellbound the jury in Federal District Court in Brooklyn with wrenching accounts from the front lines of Mexico’s bloody drug wars. He spoke about running someone down in his truck during a frantic highway gunfight. He spoke about murdering an informant in the earshot of women and children. He spoke about burying a bound and blindfolded man, who was still alive, on Mr. Guzmán’s orders.

As the prosecution’s last cooperating witness, Mr. Valdez’s appearance on the stand suggested that the government’s case was coming to an end. He seemed to have been called to deliver a gut punch to jurors. His testimony — brutal, relentless and unquestionably damaging to Mr. Guzmán — was a kind of emotional punctuation mark.

Mr. Valdez started his account with a vivid description of his first day working in what he described as Mr. Guzmán’s “security circle.” On that day in 2004, he recalled, a man he knew as Fantasma — one of the kingpin’s bodyguards whose nickname translates to “ghost” — picked him up in Culiacán and took him to an airstrip where he boarded a plane for a short flight into the Sierra Madre mountains. When Mr. Valdez landed at Mr. Guzmán’s hide-out, someone walked up to him, he said, and placed a bulletproof vest, an AK-47 and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher in his hands.

The rules of his new workplace were eventually explained to him.

He would be on duty for a month, he was told, then off for a month.

Former cartel killer Isaias Valdez Rios gave wrenching accounts of Mexico’s bloody drug wars.CreditUS Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York

Image

Former cartel killer Isaias Valdez Rios gave wrenching accounts of Mexico’s bloody drug wars.CreditUS Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York

He would sleep in the dirt outside the kingpin’s cabin.

He would be paid 2,000 pesos a month (or a little more than $175).

He was never to approach the boss. If the boss wanted to speak with him, he would be summoned.

That happened, Mr. Valdez said, 10 or 15 days after he arrived at the encampment known as The Sky. As he approached Mr. Guzmán, he recalled, the crime lord jocularly asked, “Dude, how you doing?” Mr. Guzmán wanted to know about his new recruit’s service in the Mexican special forces. He also warned the novice gunman that he had to be especially vigilant in the mountains.

“Here,” Mr. Valdez recalled the drug lord saying, “you really have to be on the lookout.”

Shortly after, Mr. Valdez, in his first assignment as one of Mr. Guzmán’s sicarios, or assassins, was ordered to accompany the kingpin’s chief of security, Alejandro Aponte, known as El Negro, to hunt down and execute an informant. Mr. Valdez told jurors that three other killers accompanied him. One was known as El Ocho. The other was nicknamed Mojo Jojo.

After the hit team arrived at the informant’s house, Mr. Valdez said, they “subdued” the women and children then found their target hiding in a bedroom. The man was taken to an indoor patio where, apparently desperate, he wrapped his arms around one of its support columns. Mr. Valdez said that Mr. Aponte shot the man first with a burst of automatic gunfire. After he fell to the ground, Mr. Valdez said, another sicario shot him in the head.

Then the hit team simply returned to their pickup truck. “We headed toward the mountains,” Mr. Valdez said.

A few years later, he recalled, he watched Mr. Guzmán interrogate — then kill — an ally of his bitter enemies, the Arellano Félix brothers. Speaking softly in the silent courtroom, Mr. Valdez recounted how the kingpin had the man brought, bound and blindfolded, to a graveyard in one of his mountain camps. The man had already been tortured so viciously with an iron, he said, that his T-shirt had been soldered into his skin. He also reeked, Mr. Valdez added, from having been locked inside a hen house for days.

Although the victim couldn’t see it, he had been placed in front of his own freshly dug grave. Mr. Valdez said Mr. Guzmán asked the man several questions, and in the middle of an answer, pulled out a .25-caliber pistol and shot him.

“Remove his handcuffs and bury him,” he recalled the crime lord saying.

But as Mr. Valdez and another gunman bent to fetch the body, they realized the small caliber bullet hadn’t killed the man.

He was still gasping for air.

“And that’s how we dumped him in the hole and buried him,” Mr. Valdez said.

A version of this article appears in print on Jan. 25, 2019, on Page A24 of the New York edition with the headline: Cartel Killer Gives Bloody Finale to El Chapo Case. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

16 of the most shocking twists and turns of El Chapo's drug-trafficking trial

businessinsider.com

16 of the most shocking twists and turns of El Chapo's drug-trafficking trial

Kelly McLaughlin

18-22 minutes

Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman.

AP

The Mexican drug lord watched from his seat in a Brooklyn courtroom as prosecutors brought out cartel cohorts, a Colombian kingpin, and even a mistress to testify against him.

The trial led to accusations of murder rooms, secret tunnels, and bribes. Mexican government leaders were also been accused of accepting bribes — including former President Enrique Pena Nieto.

Guzman pleaded not guilty to drug-trafficking charges connected to claims that he built a multibillion-dollar fortune by smuggling cocaine and other drugs across the Mexico-US border.

He is charged with 17 counts of having links to drug trafficking in the US and Mexico.

Closing arguments in the federal trial finished on January 31. Jury deliberations are expected to start on Monday.

Here are the most shocking twists and turns that happened at his trial.

1/16

Prosecutors say Guzman sent "more than a line of cocaine for every single person in the United States" in just four shipments.

In opening arguments for the case, Assistant US Attorney Adam Fels described the amount of cocaine Guzman was accused of trafficking over the border.

He said that in just four of his shipments, he sent "more than a line of cocaine for every single person in the United States," according to the BBC.

That amounts to more than 328 million lines of cocaine, Fels said.

2/16

A former Colombian kingpin who altered his face to hide his identity explained international drug trafficking to the court.

Former Colombian kingpin Juan Carlos Ramirez Abadia testified how his Norte del Valle cartel used planes and ships to bring cocaine to Mexico, where the Sinaloa cartel would smuggle it to the US under the direction of Guzman.

Abadia testified that he kept a ledger that showed how much hit men were paid and that he bribed Colombian authorities with millions of dollars.

He estimated that he smuggled 400,000 kilos of cocaine, ordered 150 killings, and amassed a billion-dollar fortune through his cartel.

He was arrested in 2007 and extradited to the United States, where he pleaded guilty to murder and drug charges.

3/16

The son of one of Sinaloa cartel's top leaders testified against Guzman.

Much of the prosecution team's hard-hitting testimony came from its star witness, Vicente Zambada Niebla.

Zambada is the son of one of the cartel's top leaders, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, who is considered one of Guzman's peers within the Sinaloa cartel hierarchy.

The younger Zambada, nicknamed El Vicentillo, described in detail the exploits of the cartel in his testimony against Guzman.

In one bit of testimony, Zambada said Guzman had the brother of another cartel leader killed because he would not shake his hand when they met to make peace in a gang war.

"When [Rodolfo] left, Chapo gave him his hand and said, 'See you later, friend,' and Rodolfo just left him standing there with his hand extended," Zambada said, according to BBC.

The 43-year-old pleaded guilty to drug-trafficking charges in Chicago in 2013 and to a trafficking-conspiracy charge in Chicago days before Guzman's trial began.

Guzman's defense attorneys have argued that Zambada's father is, in fact, the true leader of the Sinaloa cartel.

4/16

Zambada also spoke about Guzman's diamond-encrusted pistol.

Zambada testified that Guzman had an obsession with guns, and owned a bazooka and AK-47s.

His favorite, Zambada testified, was a gem-encrusted .38-caliber pistol engraved with his initials.

"On the handle were diamonds," Zambada said of the pistol, according to the New York Post.

Prosecutors released photos of the weapon in November.

6/16

Guzman's cartel had a $50 million bribe fund, according to Zambada's testimony.

7/16

El Chapo's beauty-queen wife described her husband as a "normal person."

American-born mother-of-two Emma Coronel Aispuro, 29, spoke to Telemundo about Guzman's trial in an interview that aired in December.

It was Coronel's first public interview in two years.

She told Telemundo that she had never seen her husband doing anything illegal, according to translations from the New York Post.

"[The media] made him too famous," Coronel said of her 61-year-old husband, who she married on her 18th birthday in 2007. "It's not fair."

"They don't want to bring him down from the pedestal to make him more like he is, a normal, ordinary person," she added.

8/16

A weapons smuggler said a cartel hit man had a "murder room."

Edgar Galvan testified in January that a trusted hit man for Guzman kept a "murder room" in his house on the US border, which featured a drain on the floor to make it easier to clean.

Galvan, who said his role in the Sinaloa cartel was to smuggle weapons into the US, testified in January that Antonio "Jaguar" Marrufo was the man who had the "murder room," according to the New York Post.

The room, Galvan said, featured soundproof walls and a drain.

"In that house, no one comes out," Galvan told jurors.

Both men are now in jail on firearms and gun charges.

9/16

El Chapo put spyware on his wife's and mistress' phones — and the expert who installed it was an FBI informant.

Prosecutors in Guzman's trial shared information from text messages the drug lord sent to his wife, Coronel, and a mistress named Agustina Cabanillas with the jury.

FBI Special Agent Steven Marson said US authorities obtained the information by searching records collected by a spyware software Guzman had installed on the women's phones.

Texts appeared to show Guzman and Coronel discussing the hazards of cartel life, and Guzman using Cabanillas as a go-between in the drug business.

It turns out the IT expert who installed the spyware was actually an FBI informant.

The expert had built Guzman and his allies an encrypted communication network that he later helped the FBI crack, according to The New York Times.

10/16

Guzman offered to buy his young daughter an AK-47 "so she can hang with me."

Guzman texted his wife about one of their young daughters: "I'm going to give her an AK-47 so she can hang with me."

Source: The Intelligencer.

11/16

A Colombian drug trafficker testified that Guzman boasted about paying a $100 million bribe to a former Mexican president.

Hildebrando Alexander Cifuentes-Villa, known as Alex Cifuentes, testified that Guzman paid $100 million to President Enrique Peña Nieto, who was in office from December 2012 to December 2018.

Cifuentes has previously been described as Guzman's right-hand man, who spent several years hiding in northwest Mexico with him.

"Mr. Guzman paid a bribe of $100 million to President Pena Nieto?" Jeffrey Lichtman, one of the lawyers representing Guzman, asked Cifuentes during cross-examination, according to The New York Times.

"Yes," Cifuentes responded, adding that the bribe was conveyed to Pena Nieto through an intermediary.

Guzman’s cartel allegedly used a carbon-fiber airplane to evade radars while smuggling drugs.

Cifuentes also testified that he sent Guzman shipments of cocaine in carbon-fiber airplanes specially designed to evade radar, according to the New York Times.

13/16

A witness told the court about El Chapo’s 2001 prison escape involving a laundry cart.

14/16

A 'Narcos' actor who plays El Chapo on the Netflix show made a cameo at the trial.

Alejandro Edda, 34, plays Guzman on the Netflix show "Narcos: Mexico," which chronicles the Mexican drug trade in the 1980s. He spoke to Guzman's attorneys after waiting in line in below-freezing temperatures to enter the Brooklyn federal court house.

He said that at one point, Guzman turned around and made eye contact, giving the actor a smile and a nod, according to CNN.

Edda said he decided to attend the trial because there is little video of Guzman, and he wanted to study his mannerisms for the show.

15/16

Guzman allegedly used to run drugs across the US border through a tunnel that he accessed via a pool table.

Retired US Customs agent Carlos Salazar told the jury about a series of tunnels Guzman allegedly used to run drugs across the US-Mexico border.

One tunnel discovered during a 1990 raid was half the length of a football field, lit with electricity, and had carts to move drugs across the border, according to NBC News.

The tunnel was accessed by lifting a pool table with a hydraulic system.

16/16

A one-time Guzman ally told the jury that the drug lord spent part of his billions on a personal zoo.

Guzman's former ally, Miguel Ángel Martínez, told jurors that the drug lord used his riches to buy a private zoo, a $10 million beach house, and anti-aging treatments from Switzerland.

"He had houses at every single beach," Martínez said, according to The Guardian. "He had ranches in every single state."

The zoo, Martínez said, featured lions, tigers, and panthers that you could visit via a "little train."

More: Features El Chapo El Chapo Guzman Joaquin Guzman

businessinsider.com

16 of the most shocking twists and turns of El Chapo's drug-trafficking trial

Kelly McLaughlin

18-22 minutes

Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman.

AP

- Mexican drug lord Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman is charged with 17 counts of having links to drug trafficking in the US and Mexico.

- The trial started in November 2018, and prosecutors brought in a number of people to testify against Guzman, including cartel cohorts and one of his mistresses.

- The trial exposed secret escape tunnels, naked escapes, bribes, and people within the Mexican government have been accused of accepting bribes.

The Mexican drug lord watched from his seat in a Brooklyn courtroom as prosecutors brought out cartel cohorts, a Colombian kingpin, and even a mistress to testify against him.

The trial led to accusations of murder rooms, secret tunnels, and bribes. Mexican government leaders were also been accused of accepting bribes — including former President Enrique Pena Nieto.

Guzman pleaded not guilty to drug-trafficking charges connected to claims that he built a multibillion-dollar fortune by smuggling cocaine and other drugs across the Mexico-US border.

He is charged with 17 counts of having links to drug trafficking in the US and Mexico.

Closing arguments in the federal trial finished on January 31. Jury deliberations are expected to start on Monday.

Here are the most shocking twists and turns that happened at his trial.

1/16

Prosecutors say Guzman sent "more than a line of cocaine for every single person in the United States" in just four shipments.

In opening arguments for the case, Assistant US Attorney Adam Fels described the amount of cocaine Guzman was accused of trafficking over the border.

He said that in just four of his shipments, he sent "more than a line of cocaine for every single person in the United States," according to the BBC.

That amounts to more than 328 million lines of cocaine, Fels said.

2/16

A former Colombian kingpin who altered his face to hide his identity explained international drug trafficking to the court.

Former Colombian kingpin Juan Carlos Ramirez Abadia testified how his Norte del Valle cartel used planes and ships to bring cocaine to Mexico, where the Sinaloa cartel would smuggle it to the US under the direction of Guzman.

Abadia testified that he kept a ledger that showed how much hit men were paid and that he bribed Colombian authorities with millions of dollars.

He estimated that he smuggled 400,000 kilos of cocaine, ordered 150 killings, and amassed a billion-dollar fortune through his cartel.

He was arrested in 2007 and extradited to the United States, where he pleaded guilty to murder and drug charges.

3/16

The son of one of Sinaloa cartel's top leaders testified against Guzman.

Much of the prosecution team's hard-hitting testimony came from its star witness, Vicente Zambada Niebla.

Zambada is the son of one of the cartel's top leaders, Ismael "El Mayo" Zambada, who is considered one of Guzman's peers within the Sinaloa cartel hierarchy.

The younger Zambada, nicknamed El Vicentillo, described in detail the exploits of the cartel in his testimony against Guzman.

In one bit of testimony, Zambada said Guzman had the brother of another cartel leader killed because he would not shake his hand when they met to make peace in a gang war.

"When [Rodolfo] left, Chapo gave him his hand and said, 'See you later, friend,' and Rodolfo just left him standing there with his hand extended," Zambada said, according to BBC.

The 43-year-old pleaded guilty to drug-trafficking charges in Chicago in 2013 and to a trafficking-conspiracy charge in Chicago days before Guzman's trial began.

Guzman's defense attorneys have argued that Zambada's father is, in fact, the true leader of the Sinaloa cartel.

4/16

Zambada also spoke about Guzman's diamond-encrusted pistol.

Zambada testified that Guzman had an obsession with guns, and owned a bazooka and AK-47s.

His favorite, Zambada testified, was a gem-encrusted .38-caliber pistol engraved with his initials.

"On the handle were diamonds," Zambada said of the pistol, according to the New York Post.

Prosecutors released photos of the weapon in November.

6/16

Guzman's cartel had a $50 million bribe fund, according to Zambada's testimony.

7/16

El Chapo's beauty-queen wife described her husband as a "normal person."

American-born mother-of-two Emma Coronel Aispuro, 29, spoke to Telemundo about Guzman's trial in an interview that aired in December.

It was Coronel's first public interview in two years.

She told Telemundo that she had never seen her husband doing anything illegal, according to translations from the New York Post.

"[The media] made him too famous," Coronel said of her 61-year-old husband, who she married on her 18th birthday in 2007. "It's not fair."

"They don't want to bring him down from the pedestal to make him more like he is, a normal, ordinary person," she added.

8/16

A weapons smuggler said a cartel hit man had a "murder room."

Edgar Galvan testified in January that a trusted hit man for Guzman kept a "murder room" in his house on the US border, which featured a drain on the floor to make it easier to clean.

Galvan, who said his role in the Sinaloa cartel was to smuggle weapons into the US, testified in January that Antonio "Jaguar" Marrufo was the man who had the "murder room," according to the New York Post.

The room, Galvan said, featured soundproof walls and a drain.

"In that house, no one comes out," Galvan told jurors.

Both men are now in jail on firearms and gun charges.

9/16

El Chapo put spyware on his wife's and mistress' phones — and the expert who installed it was an FBI informant.

Prosecutors in Guzman's trial shared information from text messages the drug lord sent to his wife, Coronel, and a mistress named Agustina Cabanillas with the jury.

FBI Special Agent Steven Marson said US authorities obtained the information by searching records collected by a spyware software Guzman had installed on the women's phones.

Texts appeared to show Guzman and Coronel discussing the hazards of cartel life, and Guzman using Cabanillas as a go-between in the drug business.

It turns out the IT expert who installed the spyware was actually an FBI informant.

The expert had built Guzman and his allies an encrypted communication network that he later helped the FBI crack, according to The New York Times.

10/16

Guzman offered to buy his young daughter an AK-47 "so she can hang with me."

Guzman texted his wife about one of their young daughters: "I'm going to give her an AK-47 so she can hang with me."

Source: The Intelligencer.

11/16

A Colombian drug trafficker testified that Guzman boasted about paying a $100 million bribe to a former Mexican president.

Hildebrando Alexander Cifuentes-Villa, known as Alex Cifuentes, testified that Guzman paid $100 million to President Enrique Peña Nieto, who was in office from December 2012 to December 2018.

Cifuentes has previously been described as Guzman's right-hand man, who spent several years hiding in northwest Mexico with him.

"Mr. Guzman paid a bribe of $100 million to President Pena Nieto?" Jeffrey Lichtman, one of the lawyers representing Guzman, asked Cifuentes during cross-examination, according to The New York Times.

"Yes," Cifuentes responded, adding that the bribe was conveyed to Pena Nieto through an intermediary.

- Read more about El Chapo's trial:

- El Chapo's mistress detailed how the drug lord fled Mexican Marines through a bathtub tunnel while naked in shocking testimony at his federal trial

- A witness says 'El Chapo' Guzman paid off a Mexican president with a $100 million bribe

- The Sinaloa cartel wanted to smuggle 100 tons of cocaine on an oil tanker — one of many shocking allegations from the son of one of the cartel's top leaders

- El Chapo put spyware on his wife's and mistress's phones, and the US used it to spy on him

Guzman’s cartel allegedly used a carbon-fiber airplane to evade radars while smuggling drugs.

Cifuentes also testified that he sent Guzman shipments of cocaine in carbon-fiber airplanes specially designed to evade radar, according to the New York Times.

13/16

A witness told the court about El Chapo’s 2001 prison escape involving a laundry cart.

14/16

A 'Narcos' actor who plays El Chapo on the Netflix show made a cameo at the trial.

Alejandro Edda, 34, plays Guzman on the Netflix show "Narcos: Mexico," which chronicles the Mexican drug trade in the 1980s. He spoke to Guzman's attorneys after waiting in line in below-freezing temperatures to enter the Brooklyn federal court house.

He said that at one point, Guzman turned around and made eye contact, giving the actor a smile and a nod, according to CNN.

Edda said he decided to attend the trial because there is little video of Guzman, and he wanted to study his mannerisms for the show.

15/16

Guzman allegedly used to run drugs across the US border through a tunnel that he accessed via a pool table.

Retired US Customs agent Carlos Salazar told the jury about a series of tunnels Guzman allegedly used to run drugs across the US-Mexico border.

One tunnel discovered during a 1990 raid was half the length of a football field, lit with electricity, and had carts to move drugs across the border, according to NBC News.

The tunnel was accessed by lifting a pool table with a hydraulic system.

16/16

A one-time Guzman ally told the jury that the drug lord spent part of his billions on a personal zoo.

Guzman's former ally, Miguel Ángel Martínez, told jurors that the drug lord used his riches to buy a private zoo, a $10 million beach house, and anti-aging treatments from Switzerland.

"He had houses at every single beach," Martínez said, according to The Guardian. "He had ranches in every single state."

The zoo, Martínez said, featured lions, tigers, and panthers that you could visit via a "little train."

More: Features El Chapo El Chapo Guzman Joaquin Guzman

:ALERTRED:

@THE RETIRED SKJ

nytimes.com

El Chapo Convicted in Trial That Revealed Drug Cartel’s Brutality and Corruption

9-12 minutes

BREAKING

The guilty verdict against El Chapo, the drug kingpin whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, ended the career of an outlaw who also served as a dark folk hero in Mexico.CreditEduardo Verdugo/Associated Press

Image

The guilty verdict against El Chapo, the drug kingpin whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, ended the career of an outlaw who also served as a dark folk hero in Mexico.CreditCreditEduardo Verdugo/Associated Press

The Mexican crime lord known as El Chapo was convicted on Tuesday after a three-month drug trial in New York that exposed the inner workings of his sprawling cartel, which over decades shipped tons of drugs into the United States and plagued Mexico with relentless bloodshed and corruption.

The guilty verdict against the kingpin, whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, ended the career of a legendary outlaw who also served as a dark folk hero in Mexico, notorious for his innovative smuggling tactics, his violence against competitors, his storied prison breaks and his nearly unstoppable ability to evade the Mexican authorities.

The jury’s decision came more than a week after the panel started deliberations at the trial in Federal District Court in Brooklyn where prosecutors presented a mountain of evidence against the cartel leader, including testimony from 56 witnesses, 14 of whom once worked with Mr. Guzmán. He faces life in prison at his sentencing after being convicted of all 10 counts.

Not long after the jury got the case on Feb. 4, Matthew Whitaker, the acting United States attorney general, stepped into the courtroom and shook hands with each of the trial prosecutors, wishing them good luck. Over the next several days, the jurors, appearing to scrutinize the government’s evidence, asked to be given thousands of pages of testimony, including — in an unusual move — the full testimonies of six different prosecution witnesses.

Mr. Guzmán’s trial, which took place under intense media scrutiny and tight security from bomb-sniffing dogs, police snipers and federal marshals with radiation sensors, was the first time an American jury heard details about the financing, logistics and bloody history of one of the drug cartels that have long pumped huge amounts of heroin, cocaine, marijuana and synthetic drugs like fentanyl into the United States, earning traffickers billions of dollars.

But despite extensive testimony about private jets filled with cash, bodies burned in bonfires and shocking evidence that Mr. Guzmán and his men often drugged and raped young girls, the case also revealed the operatic, even absurd, nature of cartel culture. It featured accounts of traffickers taking target practice with a bazooka, a mariachi playing all night outside a jail cell and a murder plot involving a cyanide-laced arepa.

At times, the trial was so bizarre it felt like a drug-world telenovela unfolding live in the courtroom. Last month, one of Mr. Guzmán’s mistresses tearfully proclaimed her love for him even as she testified against him from the stand. The following day, in what seemed like a coordinated show of solidarity, the kingpin and his wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro, appeared in court in matching red velvet smoking jackets.

Toward the end of the proceeding, Alejandro Edda, an actor who plays El Chapo on the Netflix series “Narcos: Mexico,” showed up at the trial to study Mr. Guzmán. The crime lord flashed an ecstatic smile when told Mr. Edda had come to see him.

Although Monday’s conviction dealt a blow to the Sinaloa drug cartel, which Mr. Guzmán, 61, helped to run for decades, the group continues to operate, led in part by the kingpin’s sons. In 2016 and 2017, the years when Mr. Guzmán was arrested for a final time and sent for prosecution to New York, Mexican heroin production increased by 37 percent and fentanyl seizures at the southwest border more than doubled, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The D.E.A., in its most recent assessment of the drug trade, noted that Mr. Guzmán’s organization and a rising power, the Jalisco New Generation cartel, “remain the greatest criminal drug threat” to the United States.

The Mexican authorities began pursuing the stocky crime lord — whose nickname translates roughly to “Shorty” — in 1993 when he was blamed for a killing that epitomized for many Mexicans the extreme violence of the country’s drug wars: the assassination of the Roman Catholic cardinal, Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, at the Guadalajara airport.

Though Mr. Guzmán was convicted that same year on charges of murdering the cardinal, he escaped from prison in 2001 — in a laundry cart pushed by a jailhouse janitor — and spent the next decade either on the lam in one of his mountain hide-outs or slipping through various police and military dragnets.

In 2012, he evaded capture by the F.B.I. and the Mexican federal police by ducking out the back door of his oceanview mansion in Los Cabos into a patch of thorn bushes. Two years later, after he was recaptured in a hotel in Mazatlán by the D.E.A. and the Mexican marines, he escaped from prison again — this time, through a lighted, ventilated, mile-long tunnel dug into the shower of his cell.

But following his last arrest — after a gunfight in Los Mochis, Mexico in 2016 — Mr. Guzmán was extradited to Brooklyn, where federal prosecutors had initially indicted him in 2009. He also faced indictment in six other American judicial districts.

The top charge of the Brooklyn indictment named Mr. Guzmán as a principal leader of a “continuing criminal enterprise” to purchase drugs from suppliers in Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Mexico’s Golden Triangle — an area including the states of Sinaloa, Durango and Chihuahua where most of the country’s heroin and marijuana are produced.

It also accused him of earning a jaw-dropping $14 billion during his career by smuggling up to 200 tons of drugs across the United States border in an array of yachts, speedboats, long-range fishing boats, airplanes, cargo trains, semi-submersible submarines, tractor-trailers filled with frozen meat and cans of jalapeños and yet another tunnel (hidden under a pool table in Agua Prieta, Mexico.)

The prosecution was years in the making and Mr. Guzmán’s trial drew upon investigative work by the F.B.I., the D.E.A., the United States Coast Guard, Homeland Security Investigations and federal prosecutors in Chicago, Miami, San Diego, Washington, New York and El Paso, Tex. The trial team also relied on scores of local American police officers and the authorities in Ecuador, Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

The evidence presented at the trial included dozens of surveillance photos, three sets of detailed drug ledgers, several of the defendant’s handwritten letters and hundreds of his most intimate — and incriminating — phone calls and text messages intercepted through four separate wiretap operations.

Prosecutors used all of this to trace Mr. Guzmán’s 30-year rise from a young, ambitious trafficker with a knack for speedy smuggling to a billionaire narco lord with an entourage of maids and secretaries, a portfolio of vacation homes — even a ranch with a personal zoo.

Andrea Goldbarg, an assistant United States attorney, called the prosecution’s case “an avalanche” during the government’s summations. Even with the help of a Power Point presentation, complete with a slide show of photos of the kingpin, Ms. Goldbarg took almost an entire day to lead the jury through it.

But the centerpiece of the government’s offering was testimony from a Shakespearean cast of cooperating witnesses who took the stand to spill the deepest secrets of Mr. Guzmán’s personal and professional lives.

Among the witnesses were the kingpin’s first employee; one of his personal secretaries; his chief Colombian cocaine supplier; the son of his closest partner and heir apparent to his empire; his I.T. expert; his top American distributor; a killer in his army of assassins; even the young mistress with whom he escaped from the Mexican marines, naked, through a tunnel that was hidden under a bathtub in his safe house.

Confronting this onslaught, Mr. Guzmán’s lawyers offered little in the way of an affirmative defense, opting instead to use cross-examination to attack the credibility of the witnesses, most of whom were seasoned criminals with their own long histories of lying, cheating, drug dealing and killing.

Late last month, there was frenzied speculation that Mr. Guzmán might testify in his own defense. But after he decided against doing so, the entire defense case lasted only 30 minutes — compared to 10 weeks for the prosecution — and consisted of a single witness and a stipulation read into the record.

In his closing argument, Jeffrey Lichtman, one of the defense lawyers, reprised a theme he first introduced during his opening statement in November, telling jurors that the real mastermind of the cartel was Mr. Guzmán’s closest partner, Ismael Zambada García.

Despite being sought by the police in Mexico for nearly 50 years, Mr. Zambada, known as El Mayo, has never been arrested. Mr. Lichtman said the reason was because Mr. Zambada had bribed virtually the entire Mexican government. Mr. Guzmán was merely “the rabbit” that the authorities chased for decades, deflecting attention from his partner, Mr. Lichtman said.

Witness after witness took the stand at the trial and talked about paying off nearly every level of the Mexican police, military and political establishment — including the shocking allegation that Mr. Guzmán gave a $100 million bribe to the country’s former president, Enrique Peña Nieto, in the run-up to Mexico’s 2012 elections. There was also testimony that bribes were paid to Genaro García Luna, one of Mexico’s top former law enforcement officers, a host of Mexican generals and police officials, and almost the entire congress of Colombia.

Emily Palmer contributed reporting.

@THE RETIRED SKJ

nytimes.com

El Chapo Convicted in Trial That Revealed Drug Cartel’s Brutality and Corruption

9-12 minutes

BREAKING

The guilty verdict against El Chapo, the drug kingpin whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, ended the career of an outlaw who also served as a dark folk hero in Mexico.CreditEduardo Verdugo/Associated Press

Image

The guilty verdict against El Chapo, the drug kingpin whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, ended the career of an outlaw who also served as a dark folk hero in Mexico.CreditCreditEduardo Verdugo/Associated Press

The Mexican crime lord known as El Chapo was convicted on Tuesday after a three-month drug trial in New York that exposed the inner workings of his sprawling cartel, which over decades shipped tons of drugs into the United States and plagued Mexico with relentless bloodshed and corruption.

The guilty verdict against the kingpin, whose real name is Joaquín Guzmán Loera, ended the career of a legendary outlaw who also served as a dark folk hero in Mexico, notorious for his innovative smuggling tactics, his violence against competitors, his storied prison breaks and his nearly unstoppable ability to evade the Mexican authorities.

The jury’s decision came more than a week after the panel started deliberations at the trial in Federal District Court in Brooklyn where prosecutors presented a mountain of evidence against the cartel leader, including testimony from 56 witnesses, 14 of whom once worked with Mr. Guzmán. He faces life in prison at his sentencing after being convicted of all 10 counts.

Not long after the jury got the case on Feb. 4, Matthew Whitaker, the acting United States attorney general, stepped into the courtroom and shook hands with each of the trial prosecutors, wishing them good luck. Over the next several days, the jurors, appearing to scrutinize the government’s evidence, asked to be given thousands of pages of testimony, including — in an unusual move — the full testimonies of six different prosecution witnesses.

Mr. Guzmán’s trial, which took place under intense media scrutiny and tight security from bomb-sniffing dogs, police snipers and federal marshals with radiation sensors, was the first time an American jury heard details about the financing, logistics and bloody history of one of the drug cartels that have long pumped huge amounts of heroin, cocaine, marijuana and synthetic drugs like fentanyl into the United States, earning traffickers billions of dollars.

But despite extensive testimony about private jets filled with cash, bodies burned in bonfires and shocking evidence that Mr. Guzmán and his men often drugged and raped young girls, the case also revealed the operatic, even absurd, nature of cartel culture. It featured accounts of traffickers taking target practice with a bazooka, a mariachi playing all night outside a jail cell and a murder plot involving a cyanide-laced arepa.

At times, the trial was so bizarre it felt like a drug-world telenovela unfolding live in the courtroom. Last month, one of Mr. Guzmán’s mistresses tearfully proclaimed her love for him even as she testified against him from the stand. The following day, in what seemed like a coordinated show of solidarity, the kingpin and his wife, Emma Coronel Aispuro, appeared in court in matching red velvet smoking jackets.

Toward the end of the proceeding, Alejandro Edda, an actor who plays El Chapo on the Netflix series “Narcos: Mexico,” showed up at the trial to study Mr. Guzmán. The crime lord flashed an ecstatic smile when told Mr. Edda had come to see him.

Although Monday’s conviction dealt a blow to the Sinaloa drug cartel, which Mr. Guzmán, 61, helped to run for decades, the group continues to operate, led in part by the kingpin’s sons. In 2016 and 2017, the years when Mr. Guzmán was arrested for a final time and sent for prosecution to New York, Mexican heroin production increased by 37 percent and fentanyl seizures at the southwest border more than doubled, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The D.E.A., in its most recent assessment of the drug trade, noted that Mr. Guzmán’s organization and a rising power, the Jalisco New Generation cartel, “remain the greatest criminal drug threat” to the United States.

The Mexican authorities began pursuing the stocky crime lord — whose nickname translates roughly to “Shorty” — in 1993 when he was blamed for a killing that epitomized for many Mexicans the extreme violence of the country’s drug wars: the assassination of the Roman Catholic cardinal, Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, at the Guadalajara airport.

Though Mr. Guzmán was convicted that same year on charges of murdering the cardinal, he escaped from prison in 2001 — in a laundry cart pushed by a jailhouse janitor — and spent the next decade either on the lam in one of his mountain hide-outs or slipping through various police and military dragnets.

In 2012, he evaded capture by the F.B.I. and the Mexican federal police by ducking out the back door of his oceanview mansion in Los Cabos into a patch of thorn bushes. Two years later, after he was recaptured in a hotel in Mazatlán by the D.E.A. and the Mexican marines, he escaped from prison again — this time, through a lighted, ventilated, mile-long tunnel dug into the shower of his cell.

But following his last arrest — after a gunfight in Los Mochis, Mexico in 2016 — Mr. Guzmán was extradited to Brooklyn, where federal prosecutors had initially indicted him in 2009. He also faced indictment in six other American judicial districts.

The top charge of the Brooklyn indictment named Mr. Guzmán as a principal leader of a “continuing criminal enterprise” to purchase drugs from suppliers in Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Mexico’s Golden Triangle — an area including the states of Sinaloa, Durango and Chihuahua where most of the country’s heroin and marijuana are produced.

It also accused him of earning a jaw-dropping $14 billion during his career by smuggling up to 200 tons of drugs across the United States border in an array of yachts, speedboats, long-range fishing boats, airplanes, cargo trains, semi-submersible submarines, tractor-trailers filled with frozen meat and cans of jalapeños and yet another tunnel (hidden under a pool table in Agua Prieta, Mexico.)

The prosecution was years in the making and Mr. Guzmán’s trial drew upon investigative work by the F.B.I., the D.E.A., the United States Coast Guard, Homeland Security Investigations and federal prosecutors in Chicago, Miami, San Diego, Washington, New York and El Paso, Tex. The trial team also relied on scores of local American police officers and the authorities in Ecuador, Colombia and the Dominican Republic.

The evidence presented at the trial included dozens of surveillance photos, three sets of detailed drug ledgers, several of the defendant’s handwritten letters and hundreds of his most intimate — and incriminating — phone calls and text messages intercepted through four separate wiretap operations.

Prosecutors used all of this to trace Mr. Guzmán’s 30-year rise from a young, ambitious trafficker with a knack for speedy smuggling to a billionaire narco lord with an entourage of maids and secretaries, a portfolio of vacation homes — even a ranch with a personal zoo.

Andrea Goldbarg, an assistant United States attorney, called the prosecution’s case “an avalanche” during the government’s summations. Even with the help of a Power Point presentation, complete with a slide show of photos of the kingpin, Ms. Goldbarg took almost an entire day to lead the jury through it.

But the centerpiece of the government’s offering was testimony from a Shakespearean cast of cooperating witnesses who took the stand to spill the deepest secrets of Mr. Guzmán’s personal and professional lives.

Among the witnesses were the kingpin’s first employee; one of his personal secretaries; his chief Colombian cocaine supplier; the son of his closest partner and heir apparent to his empire; his I.T. expert; his top American distributor; a killer in his army of assassins; even the young mistress with whom he escaped from the Mexican marines, naked, through a tunnel that was hidden under a bathtub in his safe house.

Confronting this onslaught, Mr. Guzmán’s lawyers offered little in the way of an affirmative defense, opting instead to use cross-examination to attack the credibility of the witnesses, most of whom were seasoned criminals with their own long histories of lying, cheating, drug dealing and killing.

Late last month, there was frenzied speculation that Mr. Guzmán might testify in his own defense. But after he decided against doing so, the entire defense case lasted only 30 minutes — compared to 10 weeks for the prosecution — and consisted of a single witness and a stipulation read into the record.

In his closing argument, Jeffrey Lichtman, one of the defense lawyers, reprised a theme he first introduced during his opening statement in November, telling jurors that the real mastermind of the cartel was Mr. Guzmán’s closest partner, Ismael Zambada García.

Despite being sought by the police in Mexico for nearly 50 years, Mr. Zambada, known as El Mayo, has never been arrested. Mr. Lichtman said the reason was because Mr. Zambada had bribed virtually the entire Mexican government. Mr. Guzmán was merely “the rabbit” that the authorities chased for decades, deflecting attention from his partner, Mr. Lichtman said.

Witness after witness took the stand at the trial and talked about paying off nearly every level of the Mexican police, military and political establishment — including the shocking allegation that Mr. Guzmán gave a $100 million bribe to the country’s former president, Enrique Peña Nieto, in the run-up to Mexico’s 2012 elections. There was also testimony that bribes were paid to Genaro García Luna, one of Mexico’s top former law enforcement officers, a host of Mexican generals and police officials, and almost the entire congress of Colombia.

Emily Palmer contributed reporting.

Last edited:

He has to go to the supermax right?

OJ Simpsom

Superstar

Let's see who co-signs Chapo now.

Let's see who co-signs Chapo now.