------------------------------------------------

One of the darkest moments of France’s colonial history has never been properly acknowledged. That could be about to change.

theconversation.com

The time has come for France to own up to the massacre of its own troops in Senegal

Published: March 18, 2015 11:37am EDT

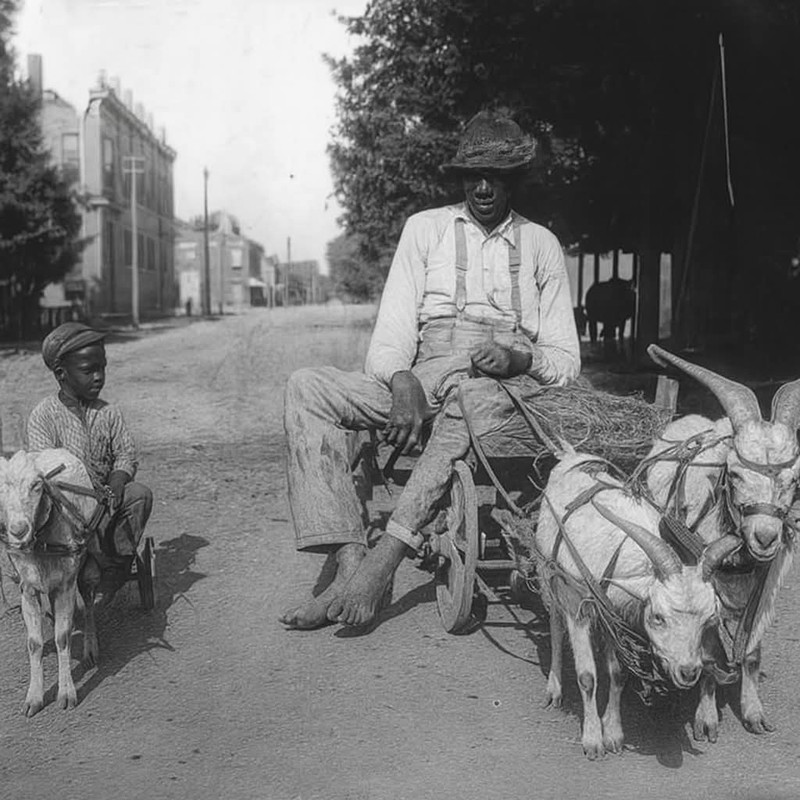

Missing: Senegalese Tirailleurs, 1940

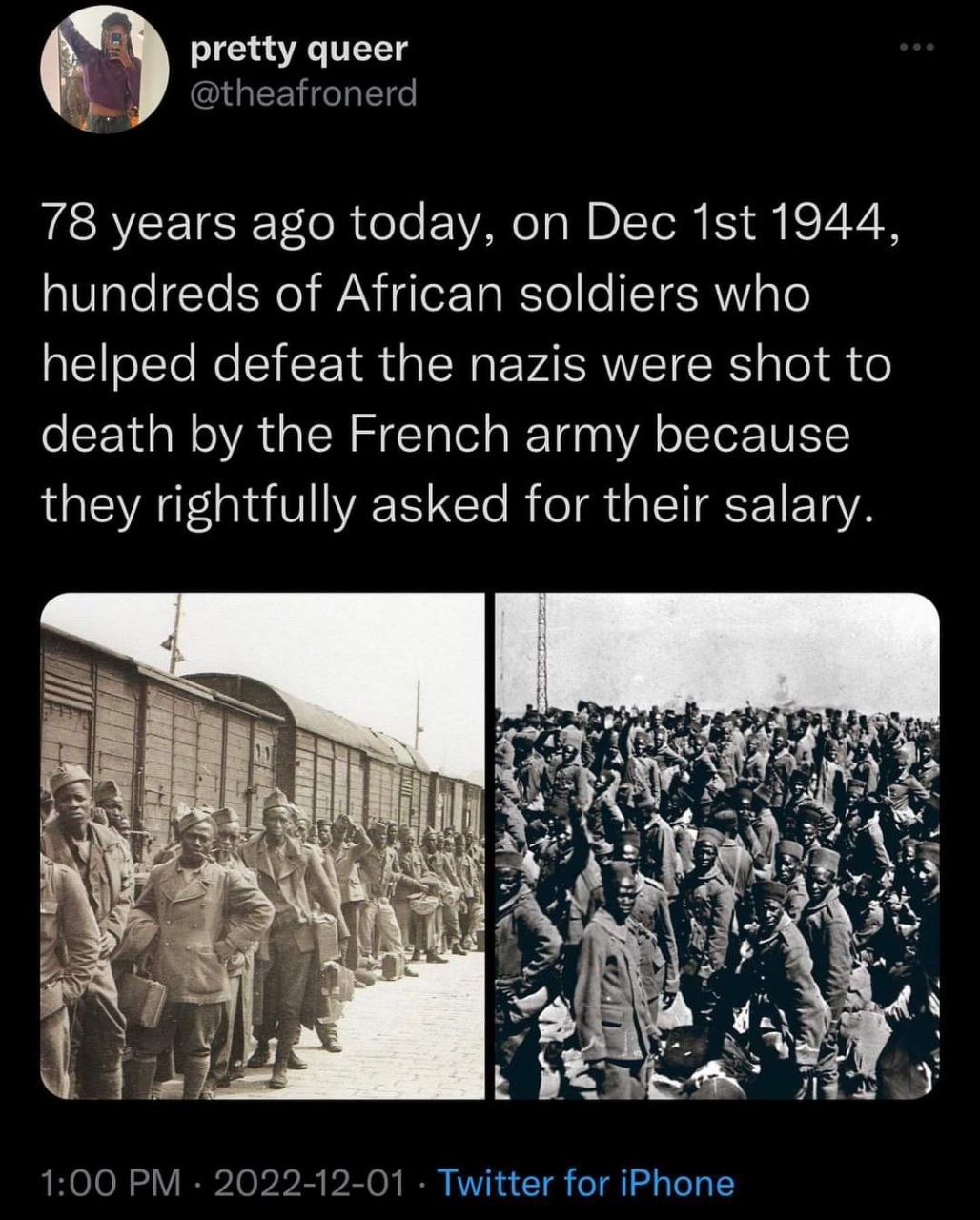

Since 2013, March 19 has marked France’s annual day of commemoration for those killed in the Algerian war of independence as well as the more minor conflicts in Morocco and Tunisia. But on the day that France commemorates those who died in its wars of decolonisation in North Africa, the truth about a massacre of sub-Saharans who fought on its side in World War II must also be acknowledged.

In December 1944, between 35 and 70 tirailleurs sénégalais – colonial troops from French West Africa – were killed at a demobilisation camp in Thiaroye, just outside Dakar in Senegal. These were soldiers who fought for France who were then gunned down in cold blood by the French army.

Then followed decades of silence on the matter. Successive governments said nothing, and when they did, as in the case of Nicolas Sarkozy, they took a “Je ne regrette rien” stance.

Then, François Hollande appeared to begin to break rank. On a trip to Dakar in October 2012, he called the events of December 1 1944 “an act of bloody repression”. He solemnly declared that France would hand over archives relating to the massacre on its 70th anniversary.

He reiterated these sentiments at a speech at the military cemetery in Thiaroye in November 2014 – on the eve of that anniversary.

However, the impression given was that the announcement of the creation of a museum on the site and the formal handing over of several boxes’ worth of archives to Senegal was designed to draw a line under Thiaroye, not open it up to more scrutiny.

What’s more, the archives transferred to the Senegalese authorities are in fact just a fraction of the material held by the French on Thiaroye. If the archive given to the Senegalese authorities is both partial and impartial, what then are the agreed facts in relation to Thiaroye – and what light has recent research thrown on the key issues?

The truth will out

By the time of the massacre, the tirailleurs, captured during the Nazi invasion in 1940, had spent four long years in prisoner of war camps in France. Following the liberation in the autumn of 1944, General de Gaulle decided that they should return home as soon as possible.

But disagreements soon surfaced regarding their demobilisation pay and some tirailleurs refused to board ships for Africa until they had received their statutory back pay. (One such dispute took place at a camp in Huyton on Merseyside.) This dispute continued at the demobilisation camp in Thiaroye and, on the morning of December 1 1944, a mix of French troops, local tirailleurs, three armoured cars with mounted machine guns and even a US army tank surrounded the camp.

The soldiers opened fire on the rebellious but unarmed tirailleurs and many were killed. The army would later officially recognise a death toll of 35 (some accounts in the days that followed claimed a further 35 deaths, as many of the injured died from their wounds). In early 1945, a further 34 soldiers were tried, convicted and jailed for sentences ranging from one to ten years for what was described as an armed mutiny.

While these facts are accepted by all sides, other elements of the story have remained hotly disputed. For the colonial authorities, this was purely a matter of military discipline, in which a heavily armed mutiny was defeated. For the colonised, Thiaroye was quite simply a massacre of unarmed soldiers and a reassertion of imperial authority on men simply demanding their rights be respected.

But thanks in large part to the tireless work of French historian Armelle Mabon, who has pored over all of the archival sources, there is now far greater certainty about some of the most contentious points.

theconversation.com

theconversation.com