These notes shine a light on the complex relationships that slaves had with their masters.

After escaping or being liberated, most former slaves were probably more than happy to never speak to their erstwhile masters.

After all, what would you say?

Though little evidence of this correspondence exists today (at least partially due to the fact that most slaves were illiterate), there are a few examples of slaves reaching out to the people who had once purchased and owned them.

Here are three of the most interesting messages:

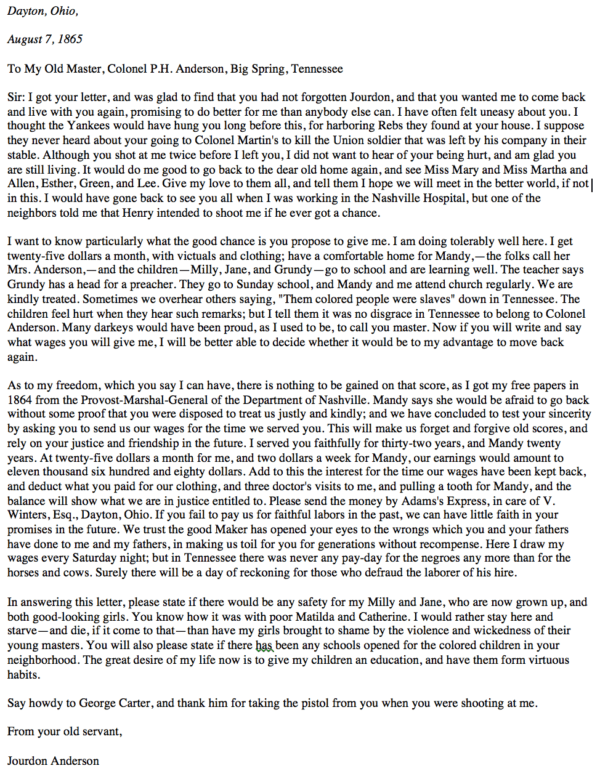

Jourdon Anderson

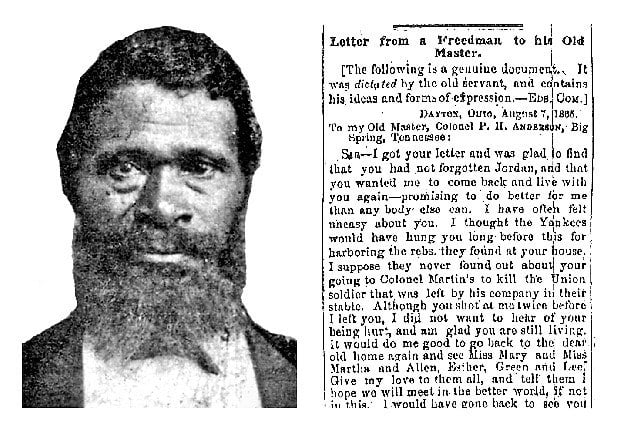

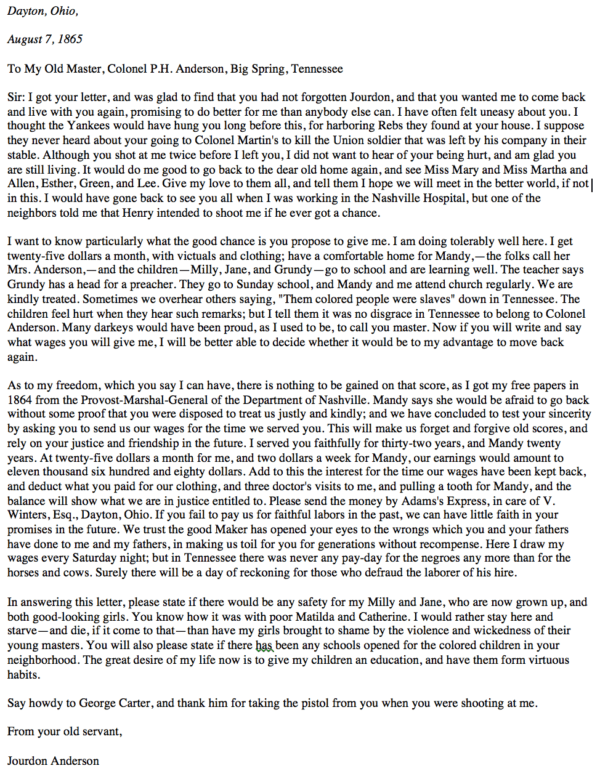

In August 1865, Jourdon Anderson received a letter from his former owner.

In it, Colonel P.H. Anderson asked Jourdon Anderson if he wouldn’t mind coming back to the Tennessee farm from which he had been liberated the previous year. Turns out, it was much harder to keep a business running when you had to pay your workers.

Unsurprisingly, Anderson decided to pass up the offer and wrote an open letter explaining why he preferred his life as a free man in Ohio. Anderson also took the opportunity to ask for the wages he and his family were owed after 32 years of unpaid labor. The total, he had tallied, amounted to $11,680, plus interest.

He casually concludes the letter with a message to an old friend: “Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.”

Anderson, who had 11 children, continued living in Ohio until his death in 1907 at the age of 81.

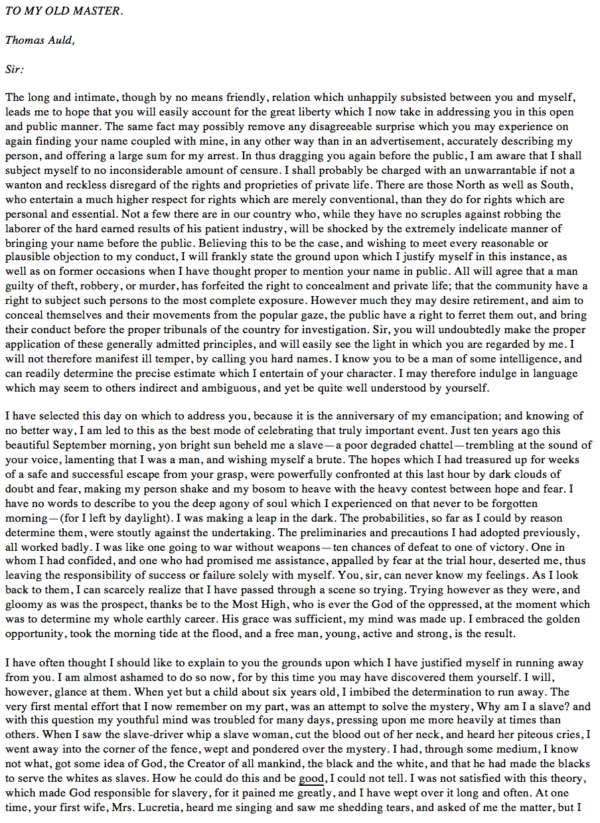

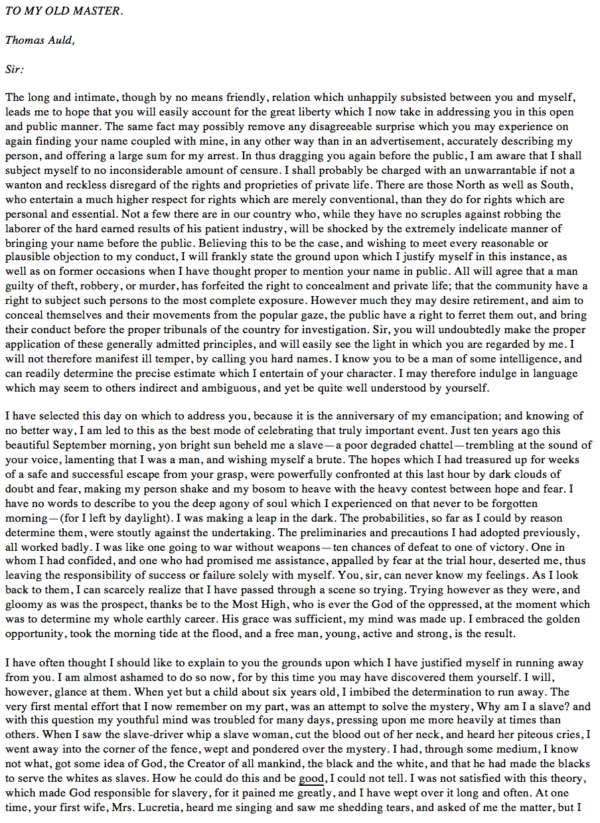

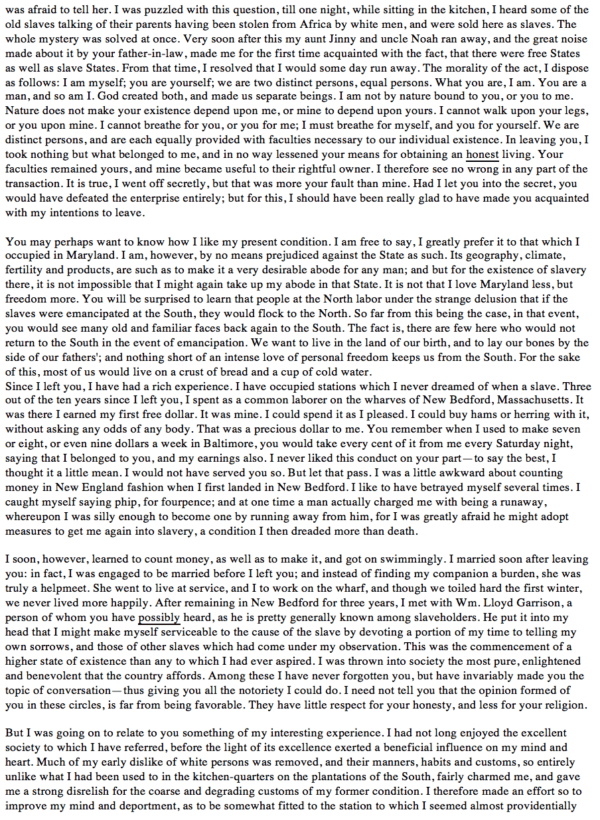

Frederick Douglass

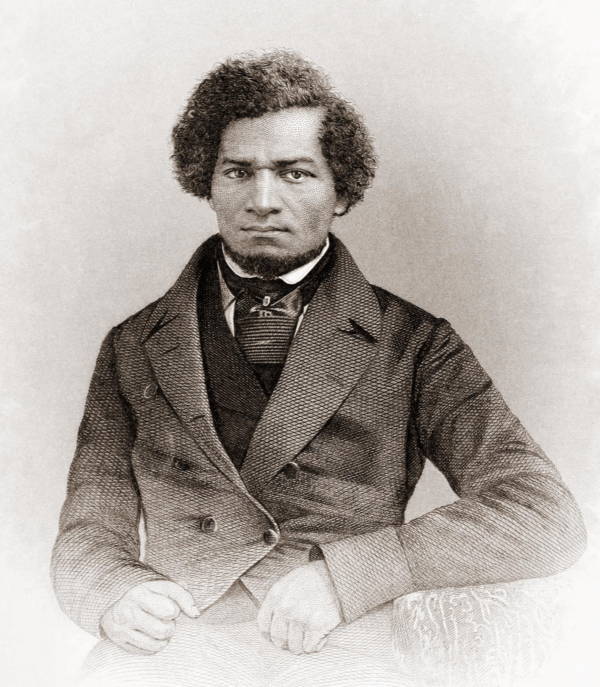

Frederick Douglass — who Donald Trump recently lauded as “an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice.” — died in 1895. But before that happened, he used his skills as a writer and statesman to promote the abolition of slavery.

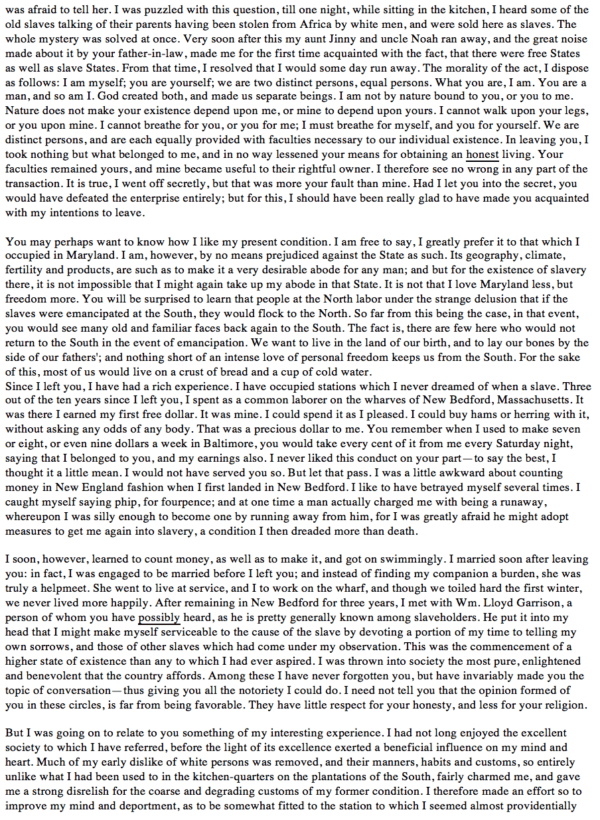

In one particularly notable publication, he addressed his former master, Thomas Auld, directly. The letter was published in Douglass’s own newspaper, North Star, in 1847, exactly one year after his escape.

In the letter, Douglass recalls his decision to run away when he was just six years old. He recounts the first time he saw a woman bleeding after being whipped. He describes the first dollar he ever earned as a free man.

He notes what it felt like to see his children learning to read and sleeping in comfortable beds.

“These dear children are ours—not to work up into rice, sugar and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel,” he wrote. “To train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can to make them useful to the world and to themselves.”

Douglass reprimands Auld several times throughout the letter, but none of his rebukes are more powerful than the way he ends his note — with startling generosity and goodwill.

“I entertain no malice towards you personally,” he wrote. “There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other. I am your fellow man, but not your slave.”

Vilet Lester

Little is known about Vilet Lester other than the fact that on August 29, 1857, she wrote a letter to her former mistress, Patsey Patterson. Lester was enslaved by a new owner, James B. Lester, when she sent the message.

“I wish to know what has ever become of my presus little girl,” she wrote, noting that she had not heard from her daughter since she had been moved.

She went on to explain that her new owner “being a man of reason and feeling wishes to grant my trubled breast that much gratification,” was willing to buy her daughter if they could locate her.

The letter is notable because of the familiar way in which Lester addresses her “Loving Miss Patsy” — almost as if the two were dear friends.

This shows the complex relationships that often developed in a system engrained so deeply into Southern culture at the time. A system in which white children and black children grew up together before understanding the social structures dividing them.

For more, visit the Duke University Special Collections Library website.

After escaping or being liberated, most former slaves were probably more than happy to never speak to their erstwhile masters.

After all, what would you say?

Though little evidence of this correspondence exists today (at least partially due to the fact that most slaves were illiterate), there are a few examples of slaves reaching out to the people who had once purchased and owned them.

Here are three of the most interesting messages:

Jourdon Anderson

In August 1865, Jourdon Anderson received a letter from his former owner.

In it, Colonel P.H. Anderson asked Jourdon Anderson if he wouldn’t mind coming back to the Tennessee farm from which he had been liberated the previous year. Turns out, it was much harder to keep a business running when you had to pay your workers.

Unsurprisingly, Anderson decided to pass up the offer and wrote an open letter explaining why he preferred his life as a free man in Ohio. Anderson also took the opportunity to ask for the wages he and his family were owed after 32 years of unpaid labor. The total, he had tallied, amounted to $11,680, plus interest.

He casually concludes the letter with a message to an old friend: “Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.”

Anderson, who had 11 children, continued living in Ohio until his death in 1907 at the age of 81.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass — who Donald Trump recently lauded as “an example of somebody who’s done an amazing job and is being recognized more and more, I notice.” — died in 1895. But before that happened, he used his skills as a writer and statesman to promote the abolition of slavery.

In one particularly notable publication, he addressed his former master, Thomas Auld, directly. The letter was published in Douglass’s own newspaper, North Star, in 1847, exactly one year after his escape.

In the letter, Douglass recalls his decision to run away when he was just six years old. He recounts the first time he saw a woman bleeding after being whipped. He describes the first dollar he ever earned as a free man.

He notes what it felt like to see his children learning to read and sleeping in comfortable beds.

“These dear children are ours—not to work up into rice, sugar and tobacco, but to watch over, regard, and protect, and to rear them up in the nurture and admonition of the gospel,” he wrote. “To train them up in the paths of wisdom and virtue, and, as far as we can to make them useful to the world and to themselves.”

Douglass reprimands Auld several times throughout the letter, but none of his rebukes are more powerful than the way he ends his note — with startling generosity and goodwill.

“I entertain no malice towards you personally,” he wrote. “There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other. I am your fellow man, but not your slave.”

Vilet Lester

Little is known about Vilet Lester other than the fact that on August 29, 1857, she wrote a letter to her former mistress, Patsey Patterson. Lester was enslaved by a new owner, James B. Lester, when she sent the message.

“I wish to know what has ever become of my presus little girl,” she wrote, noting that she had not heard from her daughter since she had been moved.

She went on to explain that her new owner “being a man of reason and feeling wishes to grant my trubled breast that much gratification,” was willing to buy her daughter if they could locate her.

The letter is notable because of the familiar way in which Lester addresses her “Loving Miss Patsy” — almost as if the two were dear friends.

This shows the complex relationships that often developed in a system engrained so deeply into Southern culture at the time. A system in which white children and black children grew up together before understanding the social structures dividing them.

Georgia Bullock Co August 29th 1857

My Loving Miss Patsy

I hav long bin wishing to imbrace this presant and pleasant opertunity of unfolding my Seans and fealings Since I was constrained to leav my Long Loved home and friends which I cannot never gave my Self the Least promis of returning to. I am well and this is Injoying good hlth and has ever Since I Left Randolph. whend I left Randolf I went to Rockingham and Stad there five weaks and then I left there and went to Richmon virgina to be Sold and I Stade there three days and was bought by a man by the name of Groover and braught to Georgia and he kept me about Nine months and he being a trader Sold me to a man by the name of Rimes and he Sold me to a man by the name of Lester and he has owned me four years and Says that he will keep me til death Siperates us without Some of my old north Caroliner friends wants to buy me again. my Dear Mistress I cannot tell my fealings nor how bad I wish to See youand old Boss and Mss Rahol and Mother. I do not [k]now which I want to See the worst Miss Rahol or mother I have thaugh[t] that I wanted to See mother but never befour did I [k]no[w] what it was to want to See a parent and could not. I wish you to gave my love to old Boss Miss Rahol and bailum and gave my manafold love to mother brothers and sister and pleas to tell them to Right to me So I may here from them if I cannot See them and also I wish you to right to me and Right me all the nuse. I do want to now whether old Boss is Still Living or now and all the rest of them and I want to [k]now whether balium is maried or no. I wish to [k]now what has Ever become of my Presus little girl. I left her in goldsborough with Mr. Walker and I have not herd from her Since and Walker Said that he was going to Carry her to Rockingham and gave her to his Sister and I want to [k]no[w] whether he did or no as I do wish to See her very mutch and Boss Says he wishes to [k]now whether he will Sell her or now and the least that can buy her and that he wishes a answer as Soon as he can get one as I wis himto buy her an my Boss being a man of Reason and fealing wishes to grant my trubled breast that mutch gratification and wishes to [k]now whether he will Sell her now. So I must come to a close by Escribing my Self you long loved and well wishing play mate as a Servant until death

Vilet Lester

of Georgia

to Miss Patsey Padison

of North Caroliner

My Bosses Name is James B Lester and if you Should think a nuff of me to right me which I do beg the faver of you as a Sevant direct your letter to Millray Bullock County Georgia. Pleas to right me So fare you well in love.

My Loving Miss Patsy

I hav long bin wishing to imbrace this presant and pleasant opertunity of unfolding my Seans and fealings Since I was constrained to leav my Long Loved home and friends which I cannot never gave my Self the Least promis of returning to. I am well and this is Injoying good hlth and has ever Since I Left Randolph. whend I left Randolf I went to Rockingham and Stad there five weaks and then I left there and went to Richmon virgina to be Sold and I Stade there three days and was bought by a man by the name of Groover and braught to Georgia and he kept me about Nine months and he being a trader Sold me to a man by the name of Rimes and he Sold me to a man by the name of Lester and he has owned me four years and Says that he will keep me til death Siperates us without Some of my old north Caroliner friends wants to buy me again. my Dear Mistress I cannot tell my fealings nor how bad I wish to See youand old Boss and Mss Rahol and Mother. I do not [k]now which I want to See the worst Miss Rahol or mother I have thaugh[t] that I wanted to See mother but never befour did I [k]no[w] what it was to want to See a parent and could not. I wish you to gave my love to old Boss Miss Rahol and bailum and gave my manafold love to mother brothers and sister and pleas to tell them to Right to me So I may here from them if I cannot See them and also I wish you to right to me and Right me all the nuse. I do want to now whether old Boss is Still Living or now and all the rest of them and I want to [k]now whether balium is maried or no. I wish to [k]now what has Ever become of my Presus little girl. I left her in goldsborough with Mr. Walker and I have not herd from her Since and Walker Said that he was going to Carry her to Rockingham and gave her to his Sister and I want to [k]no[w] whether he did or no as I do wish to See her very mutch and Boss Says he wishes to [k]now whether he will Sell her or now and the least that can buy her and that he wishes a answer as Soon as he can get one as I wis himto buy her an my Boss being a man of Reason and fealing wishes to grant my trubled breast that mutch gratification and wishes to [k]now whether he will Sell her now. So I must come to a close by Escribing my Self you long loved and well wishing play mate as a Servant until death

Vilet Lester

of Georgia

to Miss Patsey Padison

of North Caroliner

My Bosses Name is James B Lester and if you Should think a nuff of me to right me which I do beg the faver of you as a Sevant direct your letter to Millray Bullock County Georgia. Pleas to right me So fare you well in love.

For more, visit the Duke University Special Collections Library website.