No. You are - and everyone knows it.

He really wasn't - most didn't even know who he was. Again - 4 out of 5 ADOS were in the South. He was in the North. The hub for Black immigrants immigrating into the country. You stay talking about ADOS history -- and don't have a clue about us.

And again - stop using anthebellum and jim crow slurs -- that your ancestors weren't called. And if anyone fits those terms - is the person you see in the mirror daily.

Most of his followers in NYC were Black immigrants. Some Black Americans did support him -- but it was rooted in Caribbean immigrants.

"Although the movement developed here and was based in America, it was predominantly a Caribbean movement, at least until federal prosecution of Garvey in the early 1920s drew the attention of African Americans and galvanized their support of him," he said.

Garvey lived out his last years in Jamaica and England. Although he died in political obscurity in London in 1940, he eventually came to be considered the progenitor of the "black is beautiful" and Black Power movements in the U.S. in the 1960s.

"Garvey was the first man on a mass scale and level to give millions of Negroes a sense of dignity and destiny and make the Negro feel he was somebody," Martin Luther King Jr. once said. Yet until the federal government's 1922 indictment on mail fraud charges and his 1923 trial, only a smattering of African Americans took a major interest in the man who many would come to refer to as the "Black Moses," Hill found.

Before that time, Garvey's followers were largely fellow Caribbean nationals here and abroad. Hill said the UNIA, which Garvey first founded in Jamaica two years before coming to the U.S. and which he launched in New York in 1917, "took off like a rocket" between the November 1918 armistice ending World War I and the UNIA's first major gathering in August 1920, which drew some 20,000 participants to New York's Madison Square Garden.

The bulk of UNIA members and followers in this critical period were immigrants from British colonies in the Caribbean, who, bitterly disillusioned with the experience of British racism after patriotically serving in World War I, turned to Garvey and the UNIA. Many had worked on the construction of the Panama Canal and, following its completion in 1914, had flowed into the United States. Some 150,000 Caribbean natives are estimated to have worked on the building of the canal.

Caribbean nationals not only constituted Garvey's main body of followers, but they served as the primary vectors for disseminating the message of the UNIA. Within the U.S., Caribbean immigrants spread Garvey's reach by introducing his message to widely scattered communities outside of large African American population centers, including Detroit; Pittsburgh; Newport News, Va.; New Orleans; Charleston, S.C.; New Madrid, Mo.; Jacksonville, Fla.; Miami; Los Angeles; and Riverside, Calif. Meanwhile, Caribbean nationals spread Garvey's message throughout the West Indies and the countries of Central and South America, where they had been employed on the Panama Canal and on the railroads and banana plantations of the United Fruit Company, a U.S. conglomerate that specialized in the tropical fruit trade.

"Without the immigrant base, it seems unlikely that the Garvey movement would ever have arisen on the scale that it did nor as rapidly as it did," Hill said. "The two were symbiotic."

"No matter where they lived, large numbers of immigrants from the Caribbean identified very strongly with the UNIA and with Garvey because the UNIA became a way of maintaining their cultural identity and connection with the rest of the Caribbean," Hill said. As a result, Garvey's efforts helped forge a common ethnic identity for immigrants from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad, Antigua, Grenada, St. Vincent, St Lucia, the English-speaking Virgin Islands and the Bahamas.

"Even though Garvey was from Jamaica, citizens of other West Indian territories identified in large numbers with him," Hill explained. "The Caribbean diaspora's new sense of ethnic unity forged in the United States became the launching pad for this amazing movement, as well as reinforced the wider sense of Caribbean identity."

Source:

Marcus Garvey movement owes large debt to Caribbean expats, UCLA historian finds

......

Reflections on Black History - Thomas C. Fleming

REFLECTIONS ON BLACK HISTORY

Column 5: Marcus Garvey Comes To Harlem

By Thomas C. Fleming

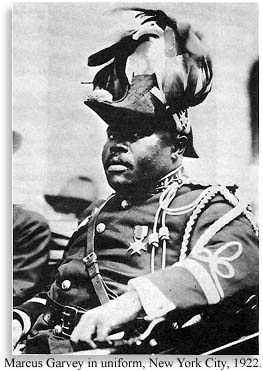

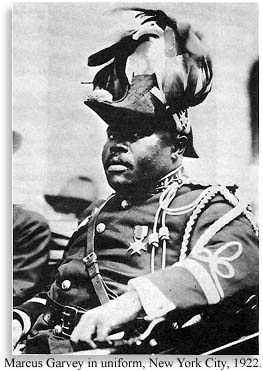

Marcus Garvey, the leader of the Back to Africa movement, arrived in Harlem in 1916, the same year I did. He was 38, an immigrant from Jamaica, and in a short time he became one of the most famous black men in America.

I was 8 years old and living on 133rd Street in Harlem, right in the middle of where the Garvey movement started.

In my neighborhood, there were probably more West Indian than American-born blacks. They wanted to succeed in America, and were very industrious, both husbands and wives &$150; always trying to start small businesses. They were looking ahead, with the goal of attaining naturalization so they could vote.

There was some antagonism between the American-born blacks and the West Indian immigrants. They all wanted to come to the United States because they could live better here. One of them told me that just about every house over there had an outhouse, and didn't have gas, electricity or running water. When they wanted to take a bath on a Saturday, they had to heat a big kettle on the stove. In Harlem, all the buildings had running water and gas, and electricity was coming into a lot of places.

These people used to say they were subjects of the king, and would tell you that back there, they could get jobs that blacks weren't getting here. But they were the lowest-paying jobs, such as petty officials. Well, the first thing we asked them was: "If you could do all those things, why did you leave?" I never heard of any American-born blacks wanting to go there.

Garvey never became an American citizen, although he lived in New York for nine years. He started the Universal Negro Improvement Association, which at one time might have had over a million members. But in New York, I think the only ones who considered him to be a leader were the West Indians.

I heard a lot about him, and then I started seeing him. They used to have parades along 7th Avenue frequently. Garvey would always be standing up in a big open-top car with his immediate aides riding with him. He dressed like an admiral. He wore one of those cockade hats that admirals wear, and a uniform. There were marchers in front and behind him, carrying banners. The women were in white dresses, and the men wore suits. They probably started about 125th Street, and marched up to 135th and 7th Avenue.

I didn't understand what it meant then. But I think it was all part of trying to attract more members. The dues weren't very much. A lot of black women joined that thing. And just about every woman I met when I was growing up worked as a domestic. They got very, very low wages.

The first thing Garvey did was take all those dollars and form a steamship company, the Black Star Line. The first ship, an aged tub, was leaky and unseaworthy, and barely made it out of New York harbor. He sold people on the idea: this is the ship that's going to take you back to Africa and carry on commerce between Africa and here. He later added two more ships, but not one of them ever landed in Africa.

His idea was to set up a colony of American blacks in Liberia. The Liberians first went along with this, but then changed their minds and wouldn't let him in, because they were afraid he would take over political power.

The U.S. government wanted to break up the movement because it saw any movement of black people as a threat. The Department of Justice in Washington thought he was trying to start a rebellion, so they accused him of bilking poor working people, and arrested him on several fraud charges for collecting the money to buy the steamers and to start other commercial businesses. He was tried in federal court and jailed in Atlanta, then later deported to Jamaica.

Two of Garvey's biggest enemies were W.E.B. Du Bois, editor of the NAACP's magazine The Crisis, and Philip Randolph, editor of The Messenger, a socialist weekly paper, and founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. They thought the Back to Africa movement was a harebrained idea &$150; just like I think.

The idea didn't occur among any blacks here because Du Bois and all of them saw how utterly ridiculous it was. Garvey was taking advantage of people with low education and low-paying jobs.

Garvey had a dream, but I don't think the Back to Africa movement was ever possible. How was he going to get enough money to move all the blacks back to Africa? And nobody wanted to go over to Africa.

But Garvey still has a lot of supporters today. There are Garvey societies throughout the United States and in other countries, and the biggest park in Harlem has been renamed Marcus Garvey Park.

©1997 by Thomas C. Fleming. Born in 1907, Fleming is a writer for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's African American weekly, which he co-founded in 1944. Email and photos: sunreport@aol.com