The Whole Country Is Starting to Look Like California

Housing prices are rising fast in red and purple states known for being easy places to build. How can that be?

The Whole Country Is Starting to Look Like California

Summarize

Housing prices are rising fast in red and purple states known for being easy places to build. How can that be?

Rogé KarmaJune 30, 2025, 7:30 AM ET

Something is happening in the housing market that really shouldn’t be. Everyone familiar with America’s affordability crisis knows that it is most acute in ultra-progressive coastal cities in heavily Democratic states. And yet, home prices have been rising most sharply in the exact places that have long served as a refuge for Americans fed up with the spiraling cost of living. Over the past decade, the median home price has increased by 134 percent in Phoenix, 133 percent in Miami, 129 percent in Atlanta, and 99 percent in Dallas. (Over that same stretch, prices in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles have increased by about 75 percent, 76 percent, and 97 percent, respectively).

This trend could prove disastrous. For much of the past half century, suburban sprawl across the Sun Belt was a kind of pressure-release valve for the housing market. People who couldn’t afford to live in expensive cities had other, cheaper places to go. Now even the affordable alternatives are on track to become out of reach for a critical mass of Americans.

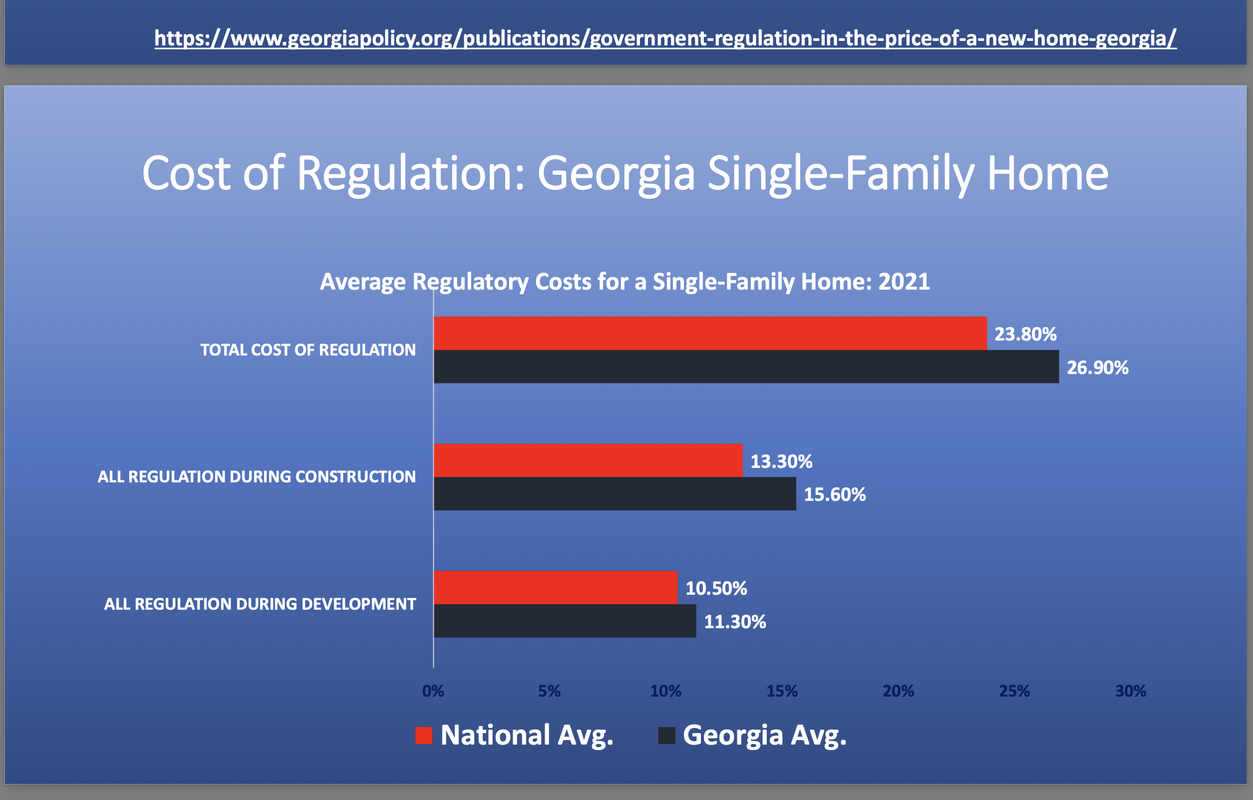

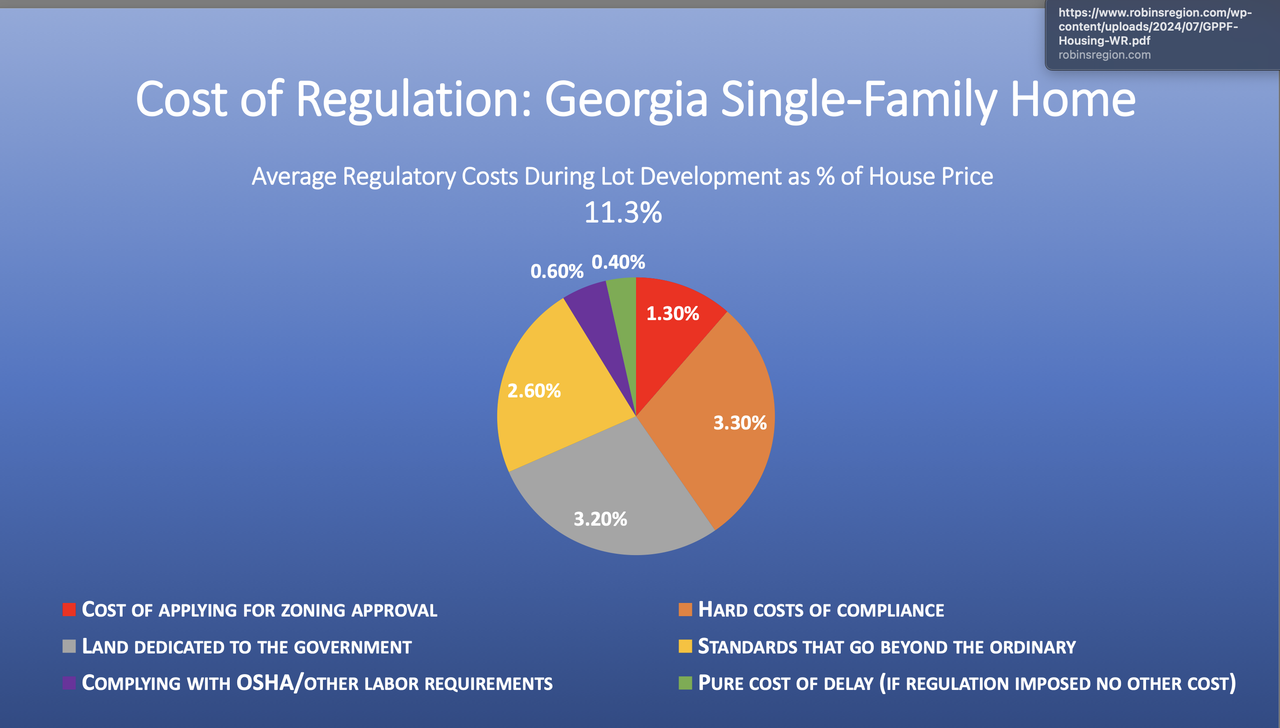

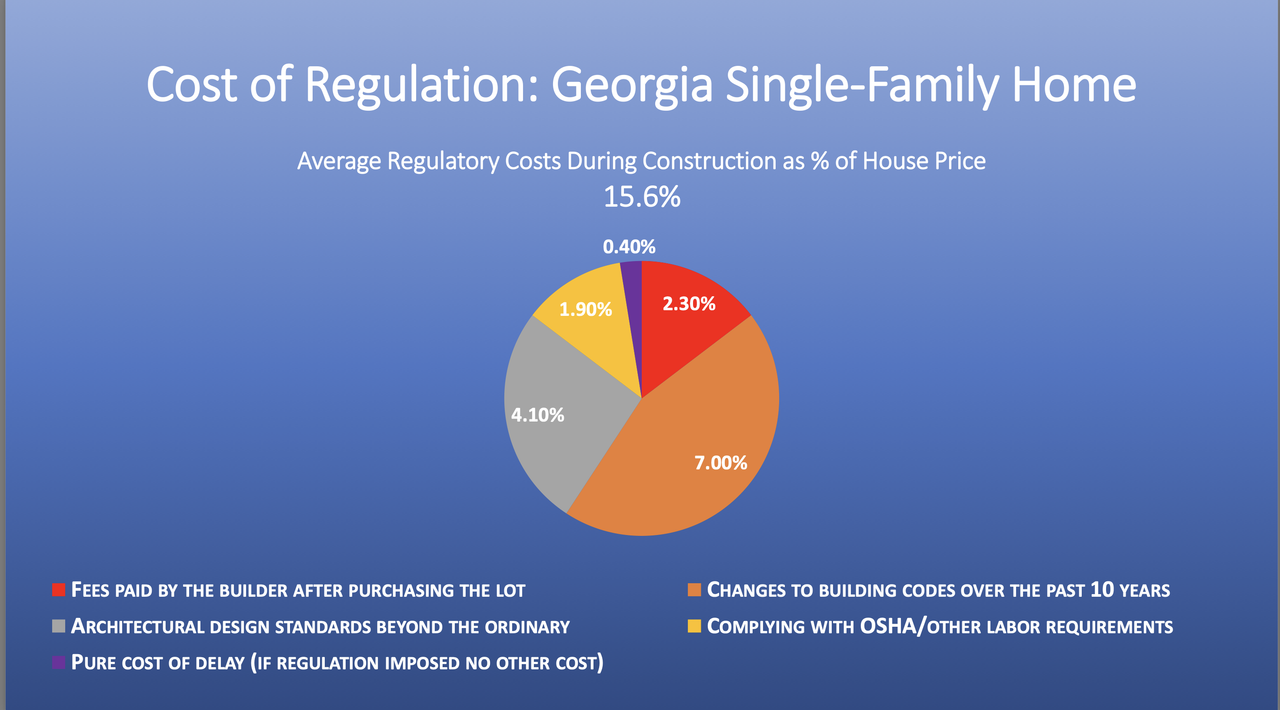

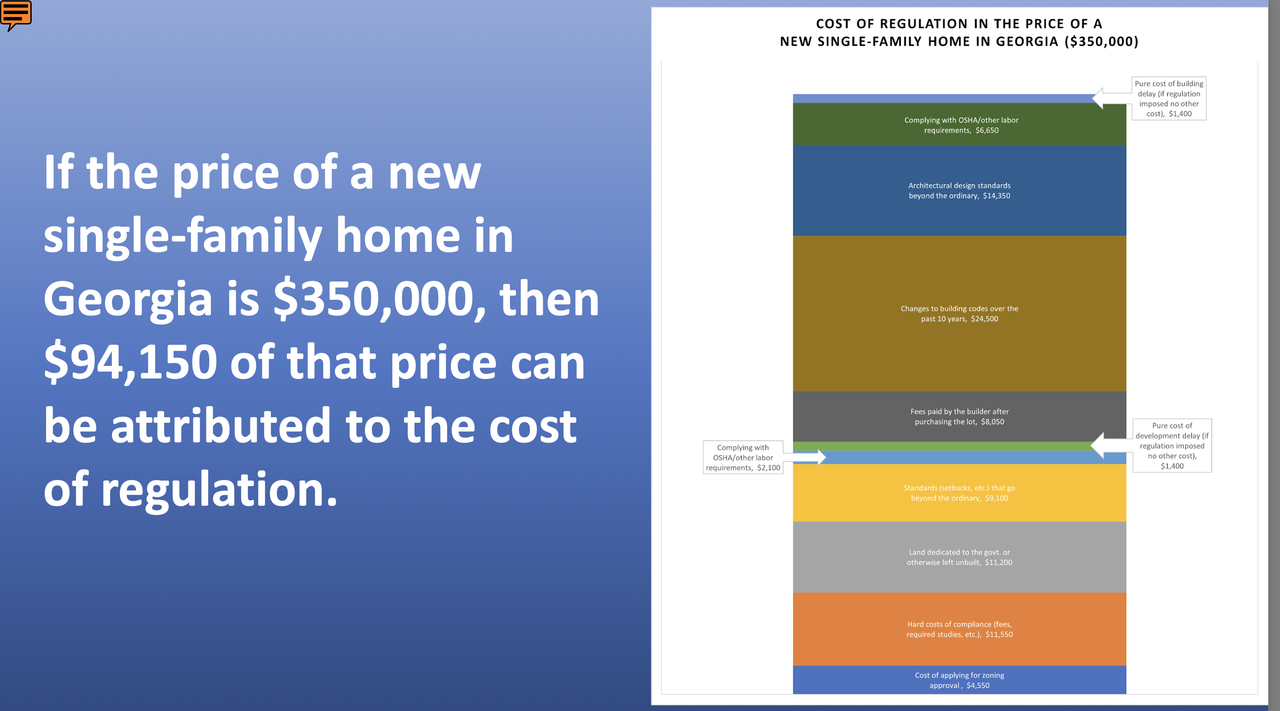

The trend also presents a mystery. According to expert consensus, anti-growth liberals have imposed excessive regulations that made building enough homes impossible. The housing crisis has thus become synonymous with feckless blue-state governance. So how can prices now be rising so fast in red and purple states known for their loose regulations?

From the March 2025 issue: How progressives froze the American dream

A tempting explanation is that the expert consensus is wrong. Perhaps regulations and NIMBYism were never really the problem, and the current push to reform zoning laws and building codes is misguided. But the real answer is that San Francisco and New York weren’t unique—they were just early. Eventually, no matter where you are, the forces of NIMBYism catch up to you.

The perception of the Sun Belt as the anti-California used to be accurate. In a recent paper, two urban economists, Ed Glaeser and Joe Gyourko, analyze the rate of housing production across 82 metro areas since the 1950s. They find that as recently as the early 2000s, booming cities such as Dallas, Atlanta, and Phoenix were building new homes at more than four times the rate of major coastal cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, on average. The fact that millions of people were being priced out of the locations with the best jobs and highest wages—so-called superstar cities—wasn’t ideal. But the Sun Belt building boom kept the coastal housing shortage from becoming a full-blown national crisis.

No longer. Although the Sun Belt continues to build far more housing than the coasts in absolute terms, Glaeser and Gyourko find that the rate of building in most Sun Belt cities has fallen by more than half over the past 25 years, in some cases by much more, even as demand to live in those places has surged. “When it comes to new housing production, the Sun Belt cities today are basically at the point that the big coastal cities were 20 years ago,” Gyourko told me. This explains why home prices in the Sun Belt, though still low compared with those in San Francisco and New York, have risen so sharply since the mid-2010s—a trend that accelerated during the pandemic, as the rise of remote work led to a large migration out of high-cost cities.

In a properly functioning housing market, the post-COVID surge in demand should have generated a massive building boom that would have cooled price growth. Instead, more than five years after the pandemic began, these places still aren’t building enough homes, and prices are still rising wildly.

As the issue of housing has become more salient in Democratic Party politics, some commentators have pointed to rising costs in the supposedly laissez-faire Sun Belt as proof that zoning laws and other regulations are not the culprit. “Blaming zoning for housing costs seems especially blinkered because different jurisdictions in the United States have very different approaches to land use regulations, and yet the housing crisis is a nationwide phenomenon,” the Vanderbilt University law professors Ganesh Sitaraman and Christopher Serkin write in a recent paper. Some argue that the wave of consolidation within the home-building industry following the 2008 financial crisis gave large developers the power to slow-walk development and keep prices high. Others say that the cost of construction has climbed so high over the past two decades that building no longer makes financial sense for developers.

Both of those claims probably account for part of the growth in housing costs, but they fall short as the main explanation. The home-building industry has indeed become more concentrated since 2008, but the slowdown in housing production in the Sun Belt began well before that. If the problem were a monopolistic market, you would expect to see higher profit margins for builders, yet Glaeser and Gyourko find that developer profits have remained roughly constant. (Other sources agree.) Likewise, construction and financing costs have risen sharply since the early 2000s—but not to the point where builders can’t turn a profit. In fact, Glaeser and Gyourko find that the share of homes selling far above the cost of production in major Sun Belt markets has dramatically increased. Put another way, there are even more opportunities for home builders to make a profit in these places; something is preventing them from taking advantage.

The Sun Belt, in short, is subject to the same antidevelopment forces as the coasts; it just took longer to trigger them. Cities in the South and Southwest have portrayed themselves as business-friendly, pro-growth metros. In reality, their land-use laws aren’t so different from those in blue-state cities. According to a 2018 research paper, co-authored by Gyourko, that surveyed 44 major U.S. metro areas, land-use regulations in Miami and Phoenix both ranked in the top 10 most restrictive (just behind Washington, D.C., and L.A. and ahead of Boston), and Dallas and Nashville were in the top 25. Because the survey is based on responses from local governments, it might understate just how bad zoning in the Sun Belt is. “When I first opened up the zoning code for Atlanta, I almost spit out my coffee,” Alex Armlovich, a senior housing-policy analyst at the Niskanen Center, a centrist think tank, told me. “It’s almost identical to L.A. in the 1990s.”

These restrictive rules weren’t a problem back when Sun Belt cities could expand by building new single-family homes at their exurban fringes indefinitely. That kind of development is less likely to be subject to zoning laws; even when it is, obtaining exceptions to those laws is relatively easy because neighbors who might oppose new development don’t exist yet. Recently, however, many Sun Belt cities have begun hitting limits to their outward sprawl, either because they’ve run into natural obstacles (such as the Everglades in Miami and tribal lands near Phoenix) or because they’ve already expanded to the edge of reasonable commute distances (as appears to be the case in Atlanta and Dallas). To keep growing, these cities will have to find ways to increase the density of their existing urban cores and suburbs. That is a much more difficult proposition. “This is exactly what happened in many coastal cities in the 1980s and ’90s,” Armlovich told me. “Once you run out of room to sprawl, suddenly your zoning code starts becoming a real limitation.”

Jerusalem Demsas: The labyrinthine rules that created a housing crisis

Glaeser and Gyourko go one step further. They hypothesize that as Sun Belt cities have become more affluent and highly educated, their residents have become more willing and able to use existing laws and regulations to block new development. They point to two main pieces of evidence. First, for a given city, the slowdown in new housing development strongly correlates with a rising share of college-educated residents. Second, within cities, the neighborhoods where housing production has slowed the most are lower-density, affluent suburbs populated with relatively well-off, highly educated professionals. In other words, anti-growth NIMBYism might be a perverse but natural consequence of growth: As demand to live in a place increases, it attracts the kind of people who are more likely to oppose new development, and who have the time and resources to do so. “We used to think that people in Miami, Dallas, Phoenix behaved differently than people in Boston and San Francisco,” Gyourko told me. “That clearly isn’t the case.”