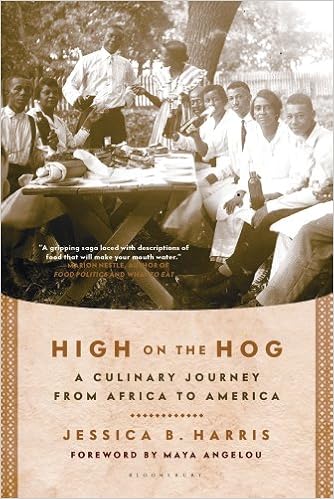

Pig Ear Sandwich: An iconic dish of the American South

This soul-food delicacy that was once about struggle and survival has been transformed into a thing of comfort.

2 July 2020

“The ears give you lots of juiciness and tasty pork flavours all at the same time,” said cook Lavette Mack as she stirred a simmering pot on the stovetop. “Add a little crunch with some slaw, give it a kick with some homemade hot sauce, put it all together in a bun and you’ve got yourself something really special."

It’s mid-morning and there’s already a small queue forming at the counter of the

Big Apple Inn, a much-loved soul food joint in the Farish Street neighbourhood of Jackson, Mississippi. “I’ll take six please,” said one customer in the colourful twang of the Deep South. “Give me two to have in, honey,” said another. Mack, who’s been working in the kitchen for more than 20 years, duly slices, spreads and stacks fresh batches of what’s become the most famous dish on the Big Apple’s menu: their pig ear sandwich.

The pig ear sandwich has been transformed into a comfort food (Credit: Simon Urwin)

“For some folk, they may be a novelty, a curiosity,” said Geno Lee, the current owner and great-grandson of the restaurant’s original founder. “But pigs’ ears are an important part of African American cuisine. They’re what we call peasant food; a part of the animal that historically even the poorest could afford. And that’s something the Inn has always stood for since it opened. Making sure everyone gets fed.”

The Big Apple story begins almost 100 years ago when Lee’s great-grandfather, Juan “Big John” Mora first arrived in Mississippi from Mexico in the early 1930s. “He jumped off the train in Jackson and stayed. He was never legal here,” said Lee. “Like many immigrants he got to work straight away, seeing how he could turn a dime.”

Pigs’ ears are an important part of African American cuisine

Big John built his own food cart, and using an old family recipe, began making and peddling hot tamales on street corners. By 1939 he’d saved enough money to purchase an old grocery store that he set about transforming into a restaurant.

“First he had to decide what to call it,” said Lee. “Around that time there was a dance craze sweeping the nation with lots of different moves like the ‘rusty dusty’ and the ‘pose and peck’. The dance was called The Big Apple and it was his absolute favourite. That’s how the place got its name.”

Next on Big John’s to-do list was finalising the bill of fare. He added his tamales to the shop’s existing offering of bologna – both are still on the menu to this day – but the Inn’s most iconic dish came about purely by accident.

“One day the butcher swung by and offered him some pigs’ ears for free. He snapped them up but had no idea what to do with them. That’s because when they’re fresh and raw, they’re big and tough. Come, I’ll show you.”

Carlos Laverne White has been coming to the Big Apple Inn for more than 50 years (Credit: Simon Urwin)

Lee led me to a back room and retrieved a slab of pink flesh the size of a bread-and-butter plate from a cold box. “At first Big John tried deep-frying them but couldn’t get them tender enough. Then he tried throwing them under the grill; same problem. Finally, he discovered that if he boiled them for two whole days, they’d eventually be good enough to eat.” He gestured to a pair of pressure cookers that rattled and hissed on top of a roaring gas flame nearby. “Thanks to these it now only takes us two hours to do the same thing.”

Lee then picked up a carving knife and cut an ear into three. “Each part is the perfect size to make a sandwich”, he said. “That was actually Big John’s invention. At that time, most people just ate the ears boiled but he decided to serve them in a bun. He also added the slaw, a splash of vinegar mustard diluted with water, and being of Mexican origin, it was also his idea to throw chillies in a pot and make a hot sauce.”

We walked back into the dining area, which was fast swelling with regulars as lunch hour approached. Lee invited me to sit and sample a “smoke and ears”: one pig ear sandwich alongside another filled with the ground, grilled meat from a Red Rose, a local smoked sausage.

The prices at Big Apple Inn have only gone up a penny or two every year (Credit: Simon Urwin)

A friendly diner looked over to my table and nodded his approval as a plate arrived with two freshly filled brioche buns. “I like to alternate – one bite of ear, one of smoke,” he said by way of recommendation. I followed his advice. The pig ear was glutinous, like a cooked lasagne sheet, with crunchier cartilage in the centre. It tasted like sweet bacon; the pork flavours followed by the after-punch of spicy chillies. The smoke had a deeper, richer tang from the beef hearts in the sausage and the char from the grill.

This is the place that made you glad that you were hungry

Noting my enthusiastic response to the meal, the diner went on to introduce himself as Carlos Laverne White. He told me that he’d been coming to the Inn for more than 50 years. “In all that time, the price has only gone up a penny or two every year. For those of us with little or no money, it means we can still eat,” he said. “I come once a week, when I can afford to pay the dollar and sixty cents. A smoke and ears fills me right up.”

An elderly gentleman in farm overalls settled opposite on the vivid, tangerine-coloured seating. Also a long-time customer, he told me he could remember a saying that went: “This is the place that made you glad that you were hungry.”

“That sentiment still applies to this day,” he told me with a broad smile. We chatted awhile and I asked him what makes eating at the Inn so special. He studied his pig ear sandwich while he pondered the reply.

“Well, you know something? All the unwanted bits of the pig – the feet, the tail, the chitterlings (intestines) and the ears – back in the day, it was what the slave owners used to give to the enslaved for their weekly rations. It’s a wonderful thing that what was once about struggle and survival has been turned over time into a thing of comfort. Soul food. It’s simple, but it’s delicious.”

The Big Apple Inn is a soul food joint in the Farish Street neighbourhood of Jackson, Mississippi (Credit: Simon Urwin)

After the lunchtime rush had passed, I headed back outside with Lee onto Farish Street – at one time Jackson’s equivalent of Memphis’ Beale Street or New Orleans’ Bourbon Street; a wildly popular place full of African American

juke joints, movie theatres and nightclubs. “The Big Apple sat at the very heart of the action,” he said. “It was packed day and night. Not only with partygoers, but activists of the Civil Rights Movement.” He pointed to an upstairs window, now missing various panes of glass. “That used to be the office of

Medgar Evers, the field secretary for the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).”

“The NAACP didn’t have much space for all their supporters, so they’d meet in the Inn and discuss their strategy for bringing an end to racial segregation. Even in those turbulent times it was a place where everyone felt safe. My grandfather was running the Inn at the time. He was mixed race – a black Latino – and an avid supporter of the movement. Anyone that got arrested, he bailed them out of jail. He took them home, gave them a meal and fresh clothes so they could get back out there and fight for justice.”

Looking up and down Farish Street, it was hard to imagine the crowds who came here to hear Evers speak, or arrived in their finery to dance the night away. In the late 60s and early 70s, businesses slowly began moving out, and now the neighbourhood is largely derelict, full of crumbling and abandoned buildings.

The Big Apple Inn swells with regulars during lunch hour (Credit: Simon Urwin)

I asked Lee why he chose to stay on and keep the business going.

“I originally studied for the priesthood then changed my mind, but the idea of ministry still appealed to me,” he replied. “I decided to become dedicated to the people of Farish Street. Selling pig ear sandwiches might not make me rich, but I leave the Big Apple Inn each night knowing that I’ve done some good, kept an important tradition alive and made sure that no-one goes home hungry. We’ve done just that throughout the pandemic in fact – staying open for take-out as we’re deemed a vital community service.”

“But, that’s not all that fills me with pride,” he added. “We now have lots of copycats in the state of Mississippi, even as far away as Memphis, Tennessee. They serve the exact same sandwich and some of them even say about their offering: ‘pig ear sandwich – just like you find on Farish Street’. So the legacy of Big John lives on and has even spread far and wide. That gives me the greatest satisfaction you could possibly imagine.”

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/XS4AUKHBECITGDJNJIU3OD5GN4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/EIQ2IMXJJLUJRAS6M2LYR5PIDE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/JCXJUTEYIP6C3OPJWPD2GP364Q.jpg)